The latest addition to Library of America’s growing list of nature and environmental titles, Rachel Carson: Silent Spring & Other Writings on the Environment, presents one of the landmark books of the twentieth century together with a judiciously chosen gathering of letters, speeches, and other writings that reveal the courage and vision of its author.

A book about the unintended consequences of pesticide use, Silent Spring was an unlikely best seller when it was published in 1962, prompting a revolution in environmental consciousness whose repercussions are still being felt decades later.

Volume editor Sandra Steingraber is Distinguished Scholar in Residence at Ithaca College. A cancer survivor and scientist, she is one of America’s leading environmental writers and anti-pollution advocates. She answered our questions about Silent Spring & Other Writings on the Environment via email.

Library of America: This edition includes a wealth of correspondence and other writings that reveal, piece-by-piece, how Silent Spring came into being. Given your already extensive familiarity with Carson’s work, were there any surprises for you in assembling this material?

Sandra Steingraber: Immersing myself in Carson’s various writings, from both before and after Silent Spring was published, was a source of joy for me. And I feel sure that readers of this new collection will likewise feel enthralled.

The pages of Carson’s correspondences with fellow scientists, the passages from her intimate letters to her beloved, Dorothy Freeman, and the transcripts of her speeches and public testimonies provide a glimpse of a masterful scientist and writer at work. We watch her unearthing evidence, discovering connections between widely disparate data sets, exploring various literary strategies that would allow her to transform that data into a spellbinding narrative, and, ultimately, defending her conclusions against her enemies in industry who sought to discredit the science that she had compiled—and, more viciously, Carson herself as a messenger of that science.

In these “other writings” we also see Carson as a breast cancer patient, suffering mightily through pain, disability, and crippling fatigue, even as she was drafting chapters about the emerging evidence linking pesticide exposure to cancer risk. Although she chose to keep her own diagnosis a strict secret, it’s clear from her personal correspondence that, in the end, she confronted her own health crisis with as much clear-eyed analysis as she did the ongoing crisis of chemical pollution and the threat of nuclear war.

In one of my favorite early letters to Dorothy, in which she declares why she must see Silent Spring through to the end, no matter how difficult the task, she writes, “I have now opened my eyes and my mind. I may not like what I see, but it does no good to ignore it.”

Ultimately, what emerges is a remarkably consistent portrait of heroism, unflinching determination, and against-all-odds bravery. Carson wasn’t one person in public and another in private. She didn’t advocate one set of ethics for her readers and another for herself. Paralyzing despair in the face of planetary calamity or personal tragedy, Carson made clear, is not an option.

As the climate crisis deepens and we now watch our own elected political leaders deny the growing evidence of harm, Carson’s exhortations are words to live by. Buck up, reader, and get to work! As she urged in her final speech, the effort to defend the planet “must and shall go on. Though the task will never be ended we must engage in it with a patience that refuses to be turned aside, with determination to overcome obstacles, and with pride that it is our privilege to contribute so greatly.”

LOA: Rebecca Solnit, Terry Tempest Williams, and Peter Matthiessen are just a few of the writers who have gone on record as admirers of Carson’s literary gifts. Where are those gifts most evident in Silent Spring? Are there aspects of it you most admire?

Steingraber: Narrowly speaking, Silent Spring is a book about the toxicological properties of nineteen pesticides. And yet it is composed in such an artful and compelling way that it provoked a profound awakening of public consciousness about the communion between human beings and their ecological world and so became a founding force of modern American environmentalism. Science alone could not have launched this movement. Science with poetry could.

What I admire greatly about her writing is the ways in which Carson deploys imagery and metaphor to do the heavy lifting for her. There are few novelistic or memoiristic elements in Carson’s books—no human characters, no dialogue, no elements of plot, no autobiographical impulses. The magic is contained in vivid visual description. Her writer’s eye is like a camera—offering panoramic views of entire ecosystems, descending into subterranean aquifers, rising with crop dusters into the sky, and then traveling into the human body to make visible the damage on subcellular levels. And then she writes like a poet, in repeating metrical patterns that make the words flow and provide a sense of majesty and symphonic, dynamic movement. We want to keep reading.

Consider, for example, how she distills our vexed situation with regard to national pest control into a single, resonant image borrowed from a Robert Frost poem: “The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road—the one ‘less traveled by’—offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth.” The binary choice that Carson lies before her readers is still ours to make, whether the subject is chemical agriculture versus organic methods or fossil fuels versus renewable energy. I’m so pleased that this quote appears on the back jacket cover.

LOA: Chapter One of Silent Spring is the arresting “Fable for Tomorrow,” a dire composite portrait of the effects of chemical poisoning on a fictitious community. What was the genesis of this opening, and what do we know about Carson’s decision to begin her book this way?

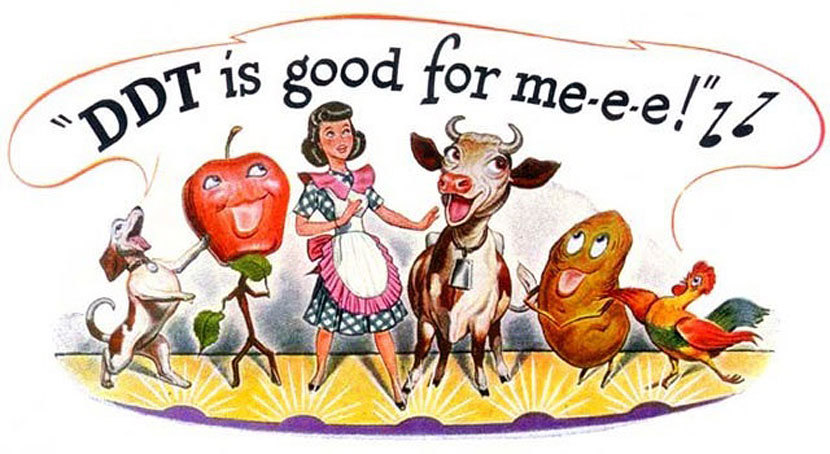

Steingraber: The most difficult writerly task that Carson assigned to herself was to upend the false but powerful narrative that the chemical companies—and their advertisers—were telling about their products and then retell it in a believable way. Remember that Carson was writing at the height of the Cold War. Chemicals had come home from World War II as heroes and were seen as patriotic. DDT in particular had saved the lives of our troops, both in Europe (where it halted a typhus epidemic) and in the Pacific (where it prevented malaria).

After the war, without any advance testing for safety the industry relentlessly promoted the use of these chemical weapons to fight insects on the home front, assuring the citizenry that DDT and its chemical cousins were miracle workers. DDT was said to be, at the same moment, a lethal assassin and a completely benign helpmate, safe enough to mothproof the baby’s blanket.

Carson needed to convince the public that, to the contrary, laying down a barrage of poisons indiscriminately across the North American continent, is neither enlightened nor advanced but brutish, ignorant, doomed to fail, and, ultimately, not in the national interest.

She begins that work in “Fable for Tomorrow,” which presents readers with a chilling mystery. And, yes, it’s arresting! The blighted world she walks us through in the book’s opening pages is a crime scene, and she narrates this first chapter like a film noir detective. The author asks, who done it? And we are hooked. “What has already silenced the voices of spring in countless towns in America? This book is an attempt to explain.” Boom.

LOA: With this volume in the Library of America series, Carson joins a roster of nature and environmental writers that includes Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and Aldo Leopold. How do you see her in relation to these forebears?

Steingraber: Joining Library of America’s pantheon of great writers is like watching an actor get their star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. So, I’m thrilled for Carson. She’s immortalized! And she entirely deserves to be.

Beyond the unsurpassed merits of Carson as a writer, I’m also keen to see her join these exalted ranks because representation matters. Women are leading the environmental movement, and women are also leading voices in environmental science. In this, Rachel Carson is our very own Wonder Woman. She is an intellectual force to be reckoned with. It’s not enough to quote her once year on Earth Day. Carson’s works needs to become required reading in high school and college classes, taken up as subjects of term papers and dissertations, inspire conferences, workshops, and films.

Rachel Carson planted the vineyards in which contemporary environmentalists, including me, are now laboring. Her three earlier books on marine biology are credited by contemporary ecologists as having anticipated complexity theory as a central tool for understanding ecosystem functioning. Her later work on the unintended consequences of pesticides helped launch the field of agroecology.

On top of all that, Silent Spring is an iconic piece of literature that altered the course of human history. I ardently hope this new collection from LOA helps position Carson as a leading voice of American letters, on par with the men who preceded her in glory. Among Thoreau, Muir, and Leopold, I would argue that Carson was the most oppositional, the most policy-focused, the most scientifically minded of the group. And yet, she was as lyrical and ecstatic and full of wonder about natural world as the rest of them.

LOA: Over time, the publication of Silent Spring led to a nationwide ban on DDT for agricultural purposes, new laws, and the Environmental Protection Agency. But have we rolled back progress in the decades since? Has the public grown complacent since Carson made her initial impact?

Steingraber: If my recent trip to the Midwest is any indication, I don’t see signs of public complacency about the ongoing environmental crisis—certainly not among young people. As part of a statewide program called Great World Texts in Wisconsin, the Center for Humanities at the University of Wisconsin assigned Silent Spring as a text to high school students across the state and then brought them together in Madison for a day-long colloquium. I received the lucky invitation to deliver the keynote. I’m happy to report that the nearly one thousand teenagers I addressed were absolutely on fire with Rachel Carson. There was not a complacent kid in the room. They know they are literally fighting for their lives in a world decimated by chemical pollution and climate instability, and they correctly saw Carson’s bad-ass, truth-to-power voice as essential for their own existential struggle.

That said, yes, progress has rolled back and is rolling back every day under the current administration. Beyond the blacklisting of individual scientists, science itself—as a way of knowing the world—is now under attack. That fact alone would shock Carson, who herself was a government scientist in the employ of the Fish and Wildlife Service.

From what I’ve seen as a scientist who works in the public interest, these trends are not attributable to citizen complacency but to growing industry influence in the body politic as well as in scientific circles. Carson called out these conflicts of interest in her later speeches but didn’t live long enough after Silent Spring’s publication to explicate the problem fully. In one of my favorite pieces of writing in this collection, Carson reveals that the reassuring report on the harmlessness of pesticides released by the National Academy of Sciences (shortly after Silent Spring’s publication) was actually authored by members of nineteen different chemical companies and four trade associations, including the National Agricultural Chemical Association. When it came to pulling back the curtain on corruption and secretive conflicts of interest, nobody did it better than Carson. That’s a skill set we need more than ever.

LOA: Like Carson, you’re both a writer and an activist. Which came first for her, do you think—and for you? How do the two modes support each other?

Steingraber: Oh, that’s easy. We are each scientists and writers first and foremost. By training and by temperament. For Carson and for me, activism and advocacy came later—and only reluctantly—when it became clear that the simple act of inculcating wonder about the natural world was necessary but insufficient to protect it from the forces of destruction. Carson would much rather have lived out her days in the woods and at the shoreline, with binoculars in hand, rather than addressing Congress and standing before cameras denouncing powerful industries. But as Rachel wrote to Dorothy, “There would be no peace for me if I kept silent.” I feel much the same. I think many scientists do.

Even so, intrepid environmental activists in the 1950s, who were organizing against aerial spraying of pesticides and filing lawsuits, gave Carson a hand with her research for Silent Spring, providing her data they had gleaned through the process of legal discovery. They eventually lost in the Supreme Court. But their early environmental activism helped open up a critical space in the culture for a book like Silent Spring. So, in my introduction to this new collection, I posit a reciprocal relationship between environmental activism and environmental science. The findings of objective science are not always politically neutral. Carson’s life and work make a powerful case for the necessity of both science and advocacy in the service of life.