The Morgan Library & Museum in New York City extends its longstanding attention to classic American writers into the world of theater with its current exhibition, Tennessee Williams: No Refuge but Writing, a concentrated look at the playwright (1911–1983) whose pioneering treatments of sexuality and society transformed American drama in the middle of the last century.

Curated by Carolyn Vega, Associate Curator of Literary & Historical Manuscripts at the Morgan, the exhibition surveys the zenith of Williams’s career—roughly two decades, from the early 1940s into the later ’50s, during which he racked up a pair of Pulitzer Prizes, a Tony Award, and three New York Drama Critics’ Circle Awards. As the exhibition’s title suggests, these were the years when Williams’s disciplined work ethic served him as a kind of sanctuary from his personal demons.

Williams once characterized his breakthrough 1944 play The Glass Menagerie as “a catastrophe of success.” But that was only after he had experienced what we might call a catastrophe of failure—the flop of his first professionally produced play, Battle of Angels, in Boston in late 1940.

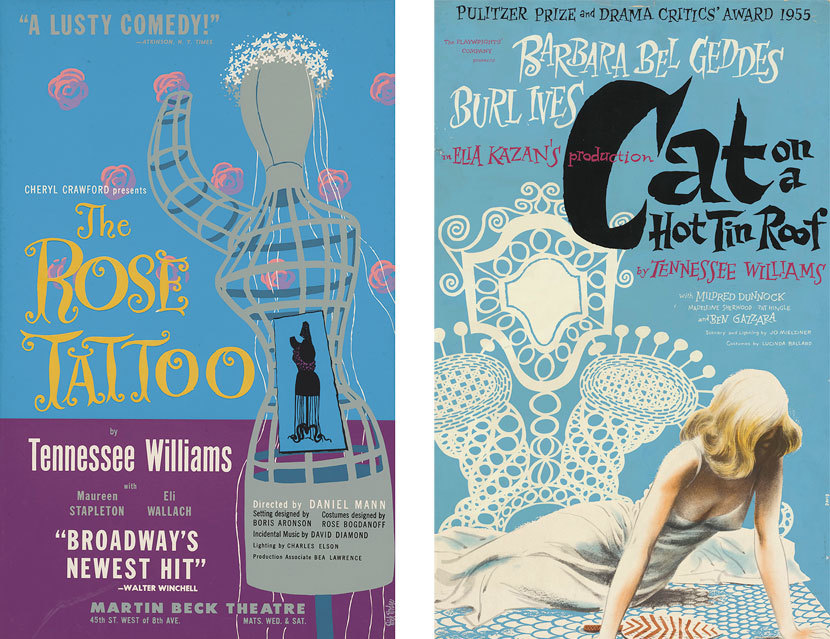

After tracing the genesis of Battle of Angels, the Morgan exhibit moves on to the string of Broadway smashes that made Williams’s name over the next decade and a half—not only The Glass Menagerie, but A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), The Rose Tattoo (1951), and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955)—before coming full circle with Orpheus Descending, the long-gestating Battle of Angels rewrite that still wasn’t quite a success when it opened in 1957.

The early focus on Battle of Angels sounds a couple of the exhibition’s major themes. After the play was condemned for its perceived indecency by no less a body than the Boston City Council, Williams wrote that he “never dreamed that such struggles [i.e., his characters’] could strike many people as filthy.” The episode was a precursor to the playwright’s many battles with censors and other bluestockings who objected to his frank portrayals of sexuality.

When Battle of Angels closed after two weeks, Williams retreated to Key West to grapple with his “blue devils”—the melancholia and worse that beset him all his life. Then as later his most dependable outlet was work: as a Morgan wall caption notes, Williams’s “wild and lyric impulses drove him to the typewriter nearly every day in a constant search for release through creative expression. At times, it was his only refuge.”

Williams long claimed that his typewriter was one of his two most important possessions (the other being his copy of Hart Crane’s Poems). On view in the exhibition is the Olivetti Lettera 32 that accompanied him in his later decades; its streamlined utilitarian simplicity may prompt a wave of nostalgia for analogue technology among visitors to the Morgan.

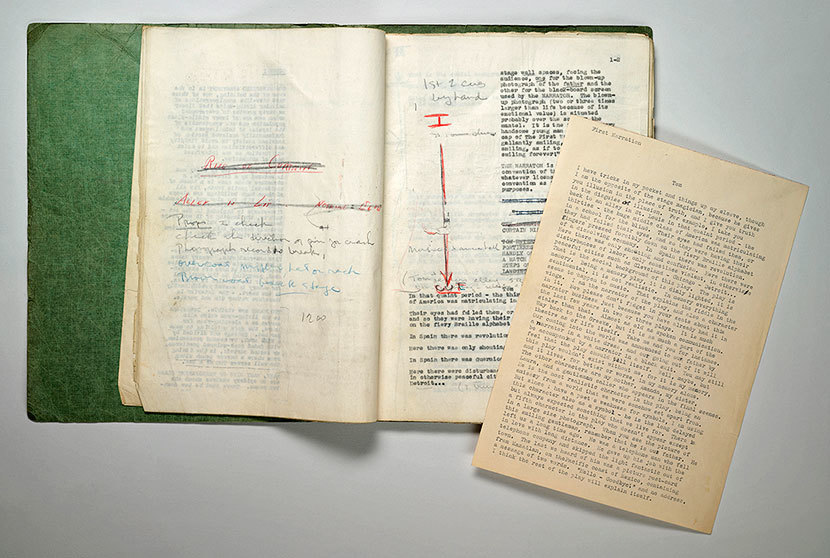

Those daily sessions at the typewriter were one reason Williams’s friends gave him the nickname “Tennacity.” At the Morgan, proof of that dedication comes in the form of typed playscripts, notebooks, and correspondence that capture a tireless creativity at work. Williams revised until the last minute (and even beyond), and it’s a revelation to see how the endings of some of the most canonical works in American theater were still up-for-grabs so close to their opening nights. To his producer Margo Jones, Williams proposes three possible conclusions for A Streetcar Named Desire; a later display lets viewers compare several competing versions of the final lines of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

This attention to written content sits comfortably alongside a range of visual art and other arresting items. The beautiful watercolor scene designs Boris Aronson created for the original productions of The Rose Tattoo and Orpheus Descending are a highlight, as are two oil paintings made by Williams himself; oil painting was his lifelong hobby, and the two works here (one a self-portrait and the other a portrait of his lover Pancho Rodriguez) offer evidence of a genuine gift.

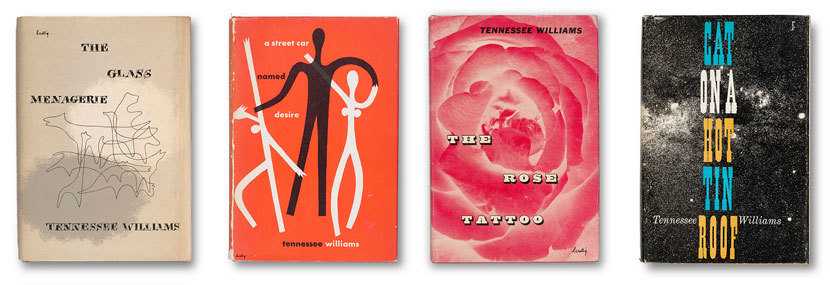

Lastly, two display cases in the center of the exhibition present Williams’s plays in markedly contrasting book form. An assortment of stylish New Directions hardcovers with dust jackets designed by Alvin Lustig beckon the viewer from one vitrine, while the adjacent one houses several vintage paperbacks issued as tie-ins to the Hollywood movie adaptations of Williams, with stars like Paul Newman and Burt Lancaster adorning their covers. Seen side by side, the two sets of books testify to a remarkable cultural moment when a single dramatist was able to combine high art with popular appeal.

Tennessee Williams: No Refuge but Writing is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City through May 13, 2018. Visit themorgan.org for complete exhibition information.

Library of America publishes The Collected Plays of Tennessee Williams in two volumes available as a boxed set.