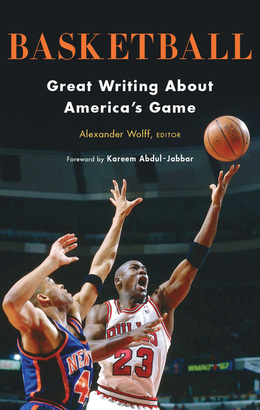

Library of America’s latest sportswriting anthology, Basketball: Great Writing About America’s Game brings together a veritable all-star lineup of writers to do justice to the game that has become a national obsession. The pieces assembled here trace the sport from its modest origins in a YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891 to its latter-day status as an entertainment colossus driven by iconic superstars—with equal time given to playground hoops and the college game.

In these pages, classic profiles by masters of long-form journalism like David Halberstam and John McPhee join more personal accounts by such writers as John Edgar Wideman, Donald Hall, and Pat Conroy. All of them exemplify the trait Kareem Abdul-Jabbar cites in the book’s introduction: “Writing about basketball isn’t just about showing enthusiasm for the game, it’s also about understanding the elegance of the sport, the chesslike intricacies of the gameplans, the emotional impact on the fans, and what it says about the society that heralds it.”

The book’s editor, Alexander Wolff, is a veteran Sports Illustrated contributor and the author or co-author of seven books on basketball, from the New York Times bestseller Raw Recruits (1990) to The Audacity of Hoop: Basketball and the Age of Obama in 2015. In 2011 he was named winner of the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame’s Curt Gowdy Media Award for lifetime coverage of the game.

Below, Wolff talks to Library of America about his selection process for Basketball, and reveals that he looked for “writing that might zig where a lot of the literature zagged.”

Library of America: In putting together Basketball: Great Writing about America’s Game, you had to immerse yourself in an enormous amount of writing about basketball over the years. What did you learn, or what struck you most forcefully during that process?

Alexander Wolff: It’s striking that the literature is fairly empty for decades. There isn’t a lot to play with until just after the middle of the twentieth century. Partly this is because baseball, boxing, horseracing, college football, and golf ruled the roost. Basketball wasn’t really taken seriously by the public, and newspaper columnists followed their readership. You have Red Smith, who was hostile to basketball, though in the terrific piece I’ve included he’s temporarily won over to the game. But he generally didn’t like it, and he was very much a tone-setter in the sportswriting lodge. Only with the late ’60s and early ’70s is there a boom in interest in the game.

The other interesting pivot point is the recent explosion of writing on the web. You could make the argument that soccer is the sport best suited for the Internet, because it’s so far-flung, but the kinds of writing about basketball on the web really struck me. Just the variety: you have the quick take off the news, of course, but there’s lots that’s very personal, written in the blogger’s voice. In the marketplace of ideas, less distinctive blogging voices were forced out and more distinctive ones got elevated. There are compelling examples in the book from the mid-2000s on, when some of the liveliest writing about the game was happening online, from people like Zach Lowe or the FreeDarko Collective.

For those who don’t know the Collective, these were a bunch of Haverford College buddies back in the early 2000s—

LOA: Not exactly a basketball powerhouse, Haverford.

Wolff: No. They stayed in touch through a fantasy league, many became grad students, and they began posting opinionated things on their league’s message board. It got pretty baroque, in a can-you-top-this kind of way. Ultimately they set up a website of NBA commentary, but it was more than that, they actually promulgated a manifesto, put a stake in the ground that said, OK, we’re going to have this particular way of looking at basketball. The era of being a fan of a team is over. We’re going to look at the whole NBA and appreciate its players as individuals, for their style, for what we impute to be their back stories, their motives. It’s like taking the concept at the heart of a fantasy league and putting it at the service of creative nonfiction.

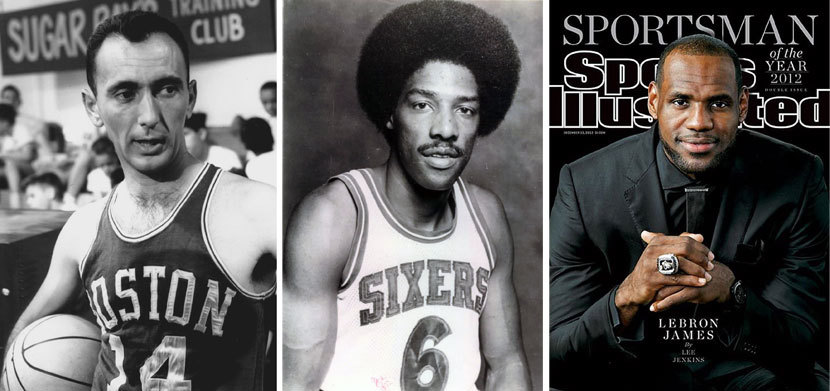

The FreeDarko piece in the anthology is about Tim Duncan and what his essential nature might be. A contributor to FreeDarko once said that the site featured a kind of music criticism, where basketball really is jazz. You’re alone in your room “listening” to an NBA player riff and reacting to his creativity. I think some writing in earlier decades hinted at that: the Mark Jacobson profile of Julius Erving I’ve included is one example. But FreeDarko took it as a given that they were reviewing players—and the game is about the players, not the teams. The FreeDarko Collective brought a liberating mentality to what they did, and laid down a marker that said, This is how far we can push the envelope writing about this game. And no, Zach Lowe at ESPN.com isn’t as wild and crazy as the FreeDarko guys are. Bill Simmons isn’t, even at his most free-associative. But there’s a certain debt being paid.

More generally I was struck by how many of the recent pieces were intensely personal. Basketball becomes a way of working through things—from Bryan Curtis using it to deal with his father’s suicide, to the sexual politics of pick-up ball when you’re a young woman like Melissa King on an inner-city court, to Brian Doyle writing about the role the game played in his relationship with his dying brother. Many of these pieces I hadn’t read before compiling the anthology—they’re not the kinds you come across in your basketball news diet, where you’re following what’s in the headlines or who’ll make the playoffs. But intimate pieces that came from out-of-the-way places were some of the most rewarding to discover and include.

LOA: Do you have a personal favorite among the pieces in Basketball? Of course, you needn’t limit yourself to just one.

Wolff: Well, it’s a bit hard to disentangle how much I like a piece from the thrill of discovering a piece I’d never read or even heard of before working on the book. But there are two, they’re very different but I think emblematic of the range of the book, and I love them both. I had no idea that either was out there.

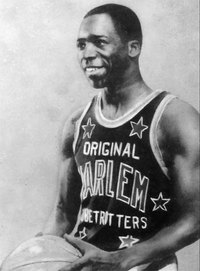

One is “Requiem for a Globetrotter” by Peter Goldman, this Newsweek veteran who’d written all these cover stories back in the ’60s and ’70s—Watergate, Vietnam, but more than anything civil-rights pieces. More than 100 cover stories. He has a fascination with race in America. He began working on a book about the Harlem Globetrotters and was confident he could sell it to a publisher. So he began to do all these interviews only to find he couldn’t get the advance he needed to do the job. Then, when this pretty obscure Globetrotter named Leon Hillard is shot dead by his wife, Peter dusts off his notes and goes to Sport magazine and offers them a profile. There’s something about the tapestry on which Goldman works in this piece: he’s sketching a very compelling character, but he’s also dealing with race—Hillard spent forty years with the Globetrotters, and the piece includes all these resonances of race in American life. The scenes Goldman sets, the quotes he uses, the characters he brings in from those forty years—we think of the Globetrotters as this happy novelty act, when in fact they were constantly fighting with management for better per diems, better working conditions, some kind of job security. And Leon was the guy who would stick his nose in it and usually paid for it. Goldman’s piece works on these different levels in such a powerful way and it really snuck up on me. I’m thrilled that we can share it between hard covers.

The other piece is by a writer who, alas, died within the past year, Brian Doyle. He’d been the longtime editor of the University of Portland’s magazine and wrote about a broad range of everyday things but had a knack for finding the spiritual in the mundane. He had a very devoted following and a passion for basketball. I’d come to find out he’d written a number of things about the sport, including the story of an argument he’d had with the Dalai Lama about the relative merits of basketball and soccer—and not knowing it was the Dalai Lama! That’s not in the book, but we do have a reminiscence about what the game meant to him and his terminally ill brother. If you’ve ever played pick-up basketball, you’re going to find wonderful resonances in it. I think it also speaks in a profound way to what it is to be a guy and suffer from that peculiarly male difficulty of sharing and expressing your feelings. Brian gets that so beautifully in the piece.

Let me add a third here: the excerpt from John Edgar Wideman’s memoir Hoop Roots. I love the form his writing takes as he describes the way he and his father related to this guy from his Pittsburgh neighborhood who played for a while in the NBA. You can hear the rhythms of the game in Wideman’s sentences, the way he drops out certain types of words, articles and the like. There’s a scuffling quality to the writing: you can hear the bounce of the ball.

LOA: In your introduction, you mention George Plimpton’s oft-cited Small Ball Theory on the writing about sports: “The smaller the ball, the more formidable the literature,” he wrote. “There are superb books about golf, very good books about baseball, not many good books about football or soccer, very few good books about basketball and no good books about beach balls.” You offer up the anthology as a rebuttal to Plimpton’s slighting of basketball.

Wolff: Plimpton is a wonderful foil to have had for the introduction, I have to say. To be fair, he last advanced that theory in 1992. Today we’re at a different place entirely. If you look at books—

LOA: That’s an important point: he’s specifically talking about books, not about magazine or other kinds of writing.

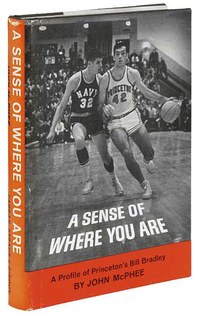

Wolff: Part of me wants to say, Hey Plimpton, heal thyself: he wrote his participatory books on every sport but basketball. All he did with hoops was a magazine article for Sports Illustrated about being with the Boston Celtics for a week during the preseason. Why that didn’t become a book I don’t know. I do think Plimpton’s critique goes back to that hockey-stick curve we were talking about earlier: when you look at the early ’60s and before, there really wasn’t much written at a high level about basketball because the sport hadn’t yet ascended to the position it now occupies. Now you have this broad collection of writers, and not just sportswriters, who want to write about the game—I mean, if Michael Lewis wants to write about your sport, people are going to read it. You begin to see that widening interest in the 1960s and ’70s, when you have these nonfiction masters writing about basketball: John McPhee on Bill Bradley, Jimmy Breslin on Al McGuire, David Halberstam on the Portland Trail Blazers.

I guess part of my motivation in rebutting Plimpton was that the literature extends far beyond books: in magazines and obviously now on the web, you can find writers who have served the game really well. Practitioners of the New Journalism in particular found satisfaction in writing about basketball. It’s a racially variegated sport where the players, rather than the owners, had agency at a time authority was being widely questioned. Magazine editors at places like Esquire and Sport and Sports Illustrated were encouraging writers to step out. I can say that at Sports Illustrated we published every week, at least until very recently. And when you get into January and February and you need to fill those pages, once the Super Bowl is over there isn’t all that much going on except basketball. So you throw a Frank Deford or Curry Kirkpatrick out on the road and you have real estate in the magazine to give them a platform. That helped create the breadth of interest in the game that, in turn, has enticed a lot of general nonfiction writers into turning to basketball. Now we see things like Steph Curry and the Warriors prompting a poet like Rowan Ricardo Philips to wax poetic, albeit in prose, about the game for the blog of The Paris Review—Plimpton’s magazine!

LOA: You mention basketball’s ascendance in the last half century, almost from obscurity. In the Curry Kirkpatrick piece you’ve included he recalls being told as late as the early ’70s that college basketball was merely a “regional sport,” with the championship game being broadcast in the decidedly non-prime time Saturday afternoon slot. Today it’s hard to imagine anyone in America not knowing what March Madness is.

Wolff: The book has two pieces—the Kirkpatrick essay on the growth of the Final Four, and Marc Jacobson’s profile of Julius Erving—about things that led me to fall hard for the game when I was young and impressionable. In Curry’s piece you have a writer talking about “my secret.” He’s out in the family’s Nash Rambler listening to the Tournament on the radio as a boy in 1956. Everyone else wants to go get ice cream and he’s listening to his “secret,” and the reward he gets is a four-overtime game that left the announcer hoarse. Jacobson is the same way with Erving in the ABA. Don’t all things that go big begin that way, as a secret that others want to be let in on? The anthology features pieces that take things that today are bigger than just about anything—like the Doctor and the Tournament—and show us how they were once just whispers. That’s what speaks to the romance of the game, that quality that leads it to get into people’s blood.

LOA: There’s a lot of writing in the book about NBA stars past and present—Bob Cousy, Michael Jordan, LeBron James—but the collection ultimately takes a much wider view. Could you talk about the prominence of playground basketball in the writing you’ve gathered?

Wolff: The playground pieces in the anthology don’t go back further than 1970 and Pete Axthelm’s The City Game. In order to write about schoolyard ball, Axthelm had to devote half of his book to the Knicks’ championship season. That was kind of the Trojan horse he used to smuggle in the playground stuff. But there was clearly curiosity about that world, even if it was perhaps driven by a slightly voyeuristic interest in the playground game’s tragedies.

LOA: Do you think that continues in the work of later writers working the playground: Rick Telander, Darcy Frey, and others?

Wolff: Not all the playground writing in the book has a tragic element to it. Rick Telander’s Heaven Is a Playground might be the most upbeat of the three book excerpts about playground ball. Darcy Frey’s The Last Shot has its tragic turns, but the great villain in that book is really the system, the college basketball system that wants to claim these guys but betrays them, it seems, at every turn.

LOA: And that villainy is then echoed in a more recent book you’ve included as an excerpt, George Dohrmann’s Play Their Hearts Out, which is not about playground ball per se but about the perils of contemporary youth basketball.

Wolff: We could easily change the name of the canopy we put over these pieces from “playground” to “grassroots.” The young prospects in Dohrmann’s book don’t play on playgrounds anymore because their knees and feet are too precious. But beyond these sorts of pieces I’ve also included Melissa King’s, about playing in Chicago, and the Brian Doyle essay, and then the book ends with David Shields’s “Life Is Not a Playground,” which might seem like a rebuke to Telander but really isn’t. O.K., heaven may be a playground—but life isn’t.

LOA: The playground has its own dynamic, which is different from the more structured, team environment with its drills and practices and game strategy. Especially for young black players it’s a kind of stage to perform on. That said, one has to be careful not to be reductive or fall prey to stereotypes: some sportswriters (though not the ones in the anthology) have opposed a purportedly “black” style of play, flashy and raw, with the more “disciplined” play epitomized by Bill Bradley, who of course was discipline personified.

Wolff: I’m delighted that the book contains a couple of pieces that subvert the easy racial assignments you’re alluding to. Charles Pierce’s profile of Larry Bird, “The Brother from Another Planet,” makes the case that Bird is the ultimate trash-talking playground player. And then Shane Battier, the subject of Michael Lewis’s “The No-Stats All Star,” is perhaps the apotheosis of the “scientific” player, African American though he may be. He comes to each game armed with video study, and does nothing that, to the naked eye at least, would account for him being out there, and yet his teams have this weird way of always winning. When I was hunting for pieces I did look for writing that might zig where a lot of the literature zagged.

LOA: As a longtime sportswriter at Sports Illustrated and as a lifelong fan of the game, could you talk about your personal connections to some of the material in Basketball?

Wolff: There are a lot of connections. I remember when the McPhee profile of Bradley came out in The New Yorker back in February 1965. I was eight years old and living in Princeton, New Jersey, where Bradley was on everybody’s lips. My parents had no interest in sports, but even they read it. I remember the Bantam Pathfinder edition, I believe it was, of A Sense of Where You Are, and it was the first basketball book I ever held and read. In college I devoured Telander’s book when it came out. As a young fact-checker at SI I had the manuscript for Deford’s “The Rabbit Hunter” plunked on my desk, which led me to call up Bob Knight and ask him whether it was indeed true that on a trip to New York City with the Ohio State varsity back in the early ’60s he had shoplifted a tie from some gift shop in Times Square.

Dave Kindred is somebody I’ve long followed and admired. Before doing the Pete Maravich obituary included in the anthology he wrote a book about basketball in Kentucky, and when I did my very first book, about playground ball around the country—kind of a Baedeker guide to where to find the best games—I cold-called Kindred and asked where in eastern Kentucky I should look for games, and he couldn’t have been more gracious. For some of the headnotes in the book I had the chance to talk to the contributors, and it was great fun to hear the back stories and nuggets about the process. So yes, for me there was a lot of revisiting old favorites—but nothing beats discovering something new and getting excited about it.