Published this month by Library of America, Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality collects more than 120 firsthand documents—speeches, letters, newspaper and magazine articles, reports, and testimonies by Americans from all walks of life—that tell the story of the American attempt to achieve racial equality in the twelve years after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox.

Among the politicians, journalists, activists, and eyewitnesses whose writings are included in Reconstruction are such well-known public figures as Ulysses S. Grant, Andrew Johnson, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Frederick Douglass, as well as dozens of lesser-known men and women. Cumulatively, these vivid eyewitness accounts bring one of the most consequential, troubling, yet still misunderstood eras in American history to life.

The book’s editor, Brooks D. Simpson, recently answered questions about Reconstruction for Library of America via email. Simpson is ASU Foundation Professor of History at Arizona State University and the author of two books on Ulysses S. Grant in addition to The Reconstruction Presidents (1998). He previously co-edited the four-volume firsthand narrative The Civil War: Told by Those Who Lived It for Library of America.

Library of America: In your introduction to the volume you write: “Most Americans don’t know very much about Reconstruction, and in many cases what they may think they know is wrong.” What do you hope readers will learn from Reconstruction? What does the experience of reading writings by those who lived during Reconstruction offer readers that standard narrative/analytical histories do not?

Brooks D. Simpson: Reconstruction is typically taught at the break in a year-long survey of American history, so it tends to get short shrift in most courses. Instructors of first-half surveys sometimes fail to reach it, while in the second-half survey Reconstruction is at best a prelude to the Gilded Age, with its stories of industrialization, urbanization, immigration, and social and political turmoil. Moreover, once upon a time accounts of Reconstruction featured assumptions about poor southern whites punished by vindictive white northerners, while giving scant attention to the fate of freedpeople deemed by most scholars to be unfit for freedom in any case. Although W. E.B. Du Bois challenged that interpretive framework in 1935 with his magisterial Black Reconstruction in America, it took until the 1960s for mainstream scholarship to contest that tale. It has taken far longer for new interpretations to take root in classrooms and textbooks: old beliefs continue to have staying power in the minds and hearts of a significant number of white Americans.

By presenting what people at the time said about what was going on in the world about them, this volume reminds us that Reconstruction was a time of great turmoil when Americans debated what the Civil War and emancipation really achieved. Was the war for reunion nothing more than that? What did freedom for over four million former slaves mean? How did Americans contest the concepts of liberty and equality, and what role would government and the governed play in resolving that dispute?

Instead of imposing on the past what we assume people must have said and meant, we can discover what they said, what they wanted, and how they viewed the issues at stake. We can hear many voices, black and white, North and South, male and female, well-known and unknown, participate in this discussion. In particular we can come away from this volume with a notion of just how fiercely contested were definitions of freedom, liberty, and equality, and the extent to which violence helped shape the outcome of America’s first great experiment in racial democracy.

LOA: Reconstruction arrives at a moment when the legacy of the Civil War and its aftermath is being more publicly and hotly fought over than at any time in at least a generation. What role do you see the anthology playing in the context of Charlottesville and the recent controversies over Confederate monuments? Could you have foreseen this context when you began selecting the contents for the book a few years ago?

Simpson: Historians are far better at recovering the past than in predicting the future, but the commemoration of the sesquicentennial of the American Civil War provided an opportunity to discuss just exactly what that war was about. Efforts to defend Confederate heritage by detaching it from the issues of slavery and racism proved counterproductive, and both scholars and the broader public contested once-dominant themes that romanticized the Old South and the Confederacy and minimized the violent repression of black freedom during Reconstruction.

This volume will remind us that Americans at the time viewed race and race relations as central to debates over the meaning of the war, with many white southerners seeking to win in peace what they had been denied in the war: the preservation of white supremacy. Readers will learn that similar beliefs also circulated throughout northern political discourse and even found expression through an American president, Andrew Johnson. These excerpts remind us that it is not so-called “political correctness” that places race at the center of Reconstruction debates: it is faithfulness to the historical record as demonstrated through contemporary documents.

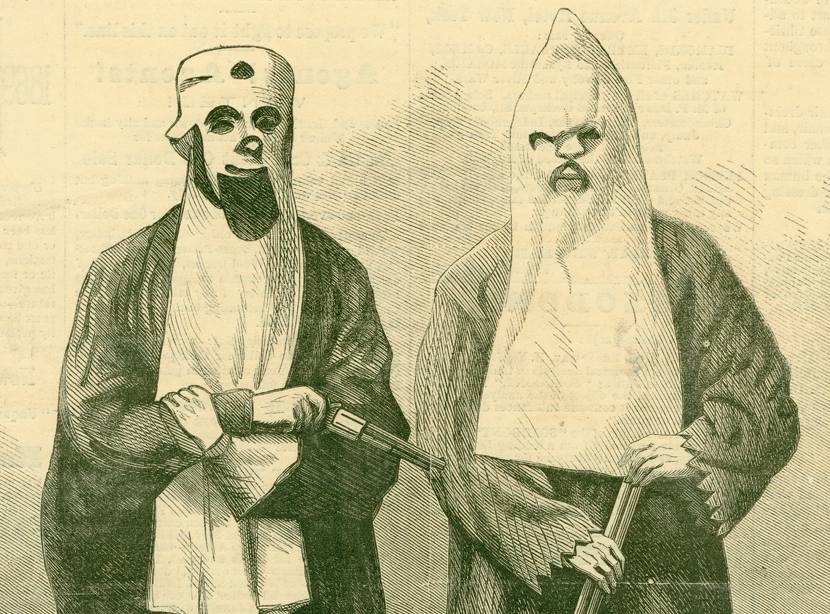

LOA: In a January 1875 dispatch from New Orleans to Washington Lieutenant General Philip H. Sheridan uses the word terrorism to describe the ongoing white supremacist violence in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Have historians of Reconstruction traditionally been reluctant to follow Sheridan in labeling these acts terrorism? How important was terrorism in determining the outcome of Reconstruction?

Simpson: White supremacist terrorism fundamentally shaped the outcome of Reconstruction. The consequences of the violent suppression of black aspirations for freedom, equality, and advancement remain with us to this day. Once some Americans celebrated such terrorists as defenders of the social order and white womanhood, notably in the film The Birth of a Nation (1915): to this day, there are those Americans who still hold in high regard famous people associated with the Ku Klux Klan and other such organizations, including Nathan Bedford Forrest, John B. Gordon, and Wade Hampton. Perpetrators of terrorist activities not only intimidated or murdered their opponents in the South, but they also wore down what will there was among white Northerners to resist them. White southerners fought with a persistent determination to preserve white supremacy that they rarely showed in fighting for independence. Only now are historians acknowledging the importance of terrorism in undermining Reconstruction’s promise.

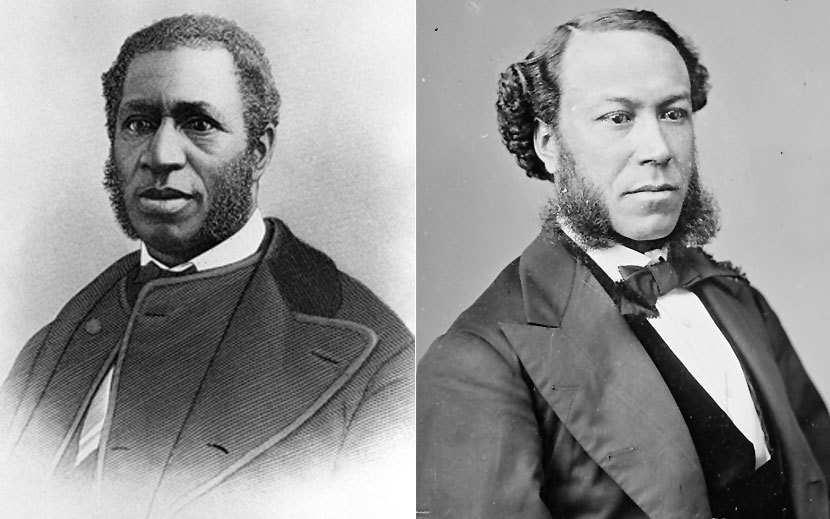

LOA: Two major figures in the volume are Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant. How do they differ, both in terms of their Reconstruction policies and the way they exercised presidential leadership? What do their speeches and messages tell us about how they chose to communicate with the public?

Simpson: Andrew Johnson gave short shrift to black aspirations, preferring to characterize Reconstruction as a restoration of the old order shorn of slavery and dreams of independence. He wanted both the Union and the Constitution as they were before 1860. The Tennessean could be blunt and even profane in articulating his views in language that escalated political divisions. Although Ulysses S. Grant was committed to sectional reconciliation, he became a staunch advocate of protecting black rights in the postwar era, defining that achievement as one of the fruits of northern victory. Johnson’s obstructionism led to his impeachment and near-conviction, but it also stalled efforts to achieve a more thoroughgoing Reconstruction by forcing Republicans to rally behind veto-proof legislative measures.

In contrast, despite his popularity, Grant was unable to achieve more than momentary triumphs on behalf of black freedom and equality, and retired from office frustrated that he had been unable to achieve more in the face of white resistance and apathy. Not known as a public speaker, Grant nevertheless set forth his views in a clear and concise matter in several of his presidential messages, most notably in his special message of January 13, 1875, concerning affairs in Louisiana. Yet one can sense in his strident denunciation of white southern terrorism and northern white apathy that he knew he was fighting a losing battle.

LOA: Many famous public figures are represented in these pages, but readers also encounter several remarkable spokesmen for the rights of freed people who might be less familiar in 2018, such as Congressmen Robert Brown Elliott, Richard Harvey Cain, Joseph H. Rainey, James T. Rapier, and John R. Lynch. Could you talk a little bit about these men and their significance, both during Reconstruction and for us today?

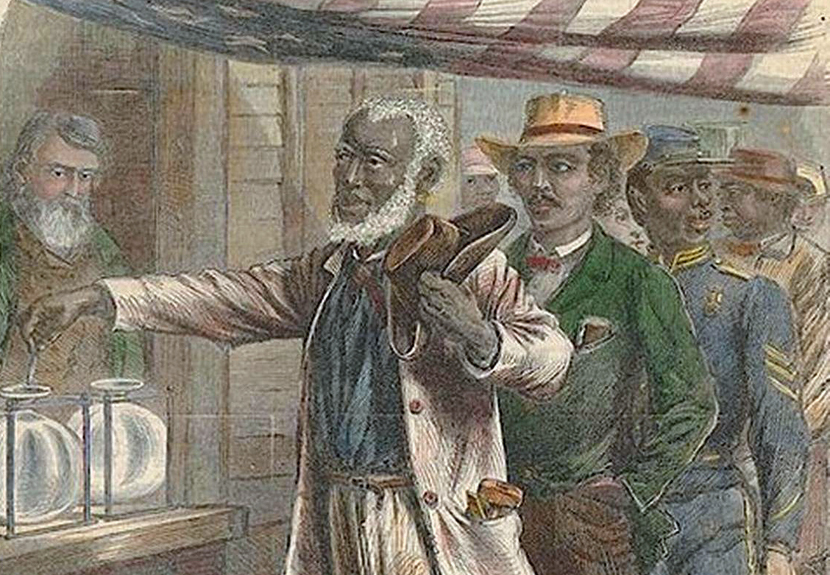

Simpson: Reconstruction witnessed large numbers of black Americans becoming involved in the political process for the first time. Former slaves voted in state elections in 1867 and 1868 and participated in such numbers in the 1868 presidential contest that Grant owed his popular vote majority to their turnout at the polls, as many voters defied threats of violence to cast their ballots. Black Americans also secured election to office and used that opportunity to express what they wanted, namely freedom, equality, and opportunity. African American members of Congress engaged their white critics and made the case that they exemplified American values while demonstrating that notions of black inferiority and unfitness for office were utter nonsense. They articulated a vision of equality that remains compelling today.

LOA: You’ve been studying and writing about Reconstruction for decades. In putting together the volume, what document did you come across that was the most interesting/surprising?

Simpson: While there are many documents reprinted in the volume that merit repeated reading, including those composed by the freedpeople themselves, I continue to be startled by Andrew Johnson’s remarks to a regiment of black veterans returning home in October 1865. We are used to presidents praising the service of members of our armed forces, but Johnson used the opportunity before him to admonish and advise the men before him to make sure that they proved worthy of the freedom for which they had fought. The result is a discordant message that reminds me that Johnson held deep and unconquerable prejudices that underlay his approach to emancipation.

LOA: If you could persuade all Americans to read just one piece in the collection, which one would it be?

Simpson: In December 1874 and January 1875 Ulysses S. Grant twice addressed the nation on political violence in Louisiana. Both addresses are worth reading, but it is in the second message that the president lays it on the line in words that set forth the nation’s failure to realize the promise of Reconstruction. He pointed out that while Reconstruction’s critics continued to focus on election squabbles, the terrorists who murdered perhaps upwards of a hundred people at Colfax, Louisiana, on April 13, 1873, remained free, “and no way can be found in this boasted land of civilization and Christianity to punish the perpetrators of this bloody and monstrous crime.” Rarely has an American president spoken so bluntly . . . and honestly.