This February, in honor of Black History Month, Library of America has released Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality, a sweeping new anthology edited by historian Brooks D. Simpson that brings to dramatic life the tumultuous twelve-year period when the nation sought to reconstitute itself after the Civil War and the end of slavery. Through more than 120 speeches, letters, newspaper accounts, and eyewitness testimonies, Reconstruction allows reader to experience this crucial period as it unfolded, and to discover in its vivid descriptions of domestic terrorism, voter suppression, presidential impeachment, and the quest for a full and equal citizenship an inescapable relevance for today.

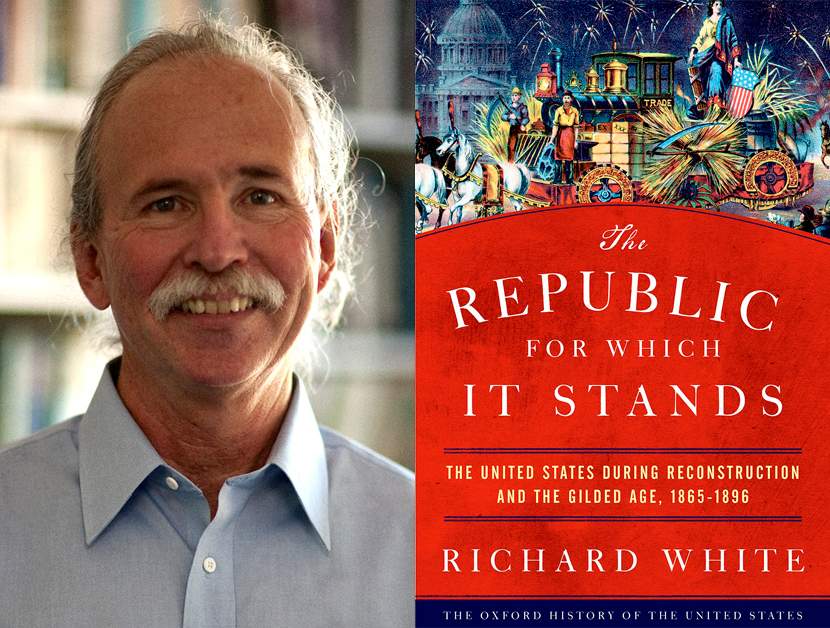

As such, it makes a perfect companion to historian Richard White‘s new book, The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865‒1896, the latest volume in the magisterial Oxford History of the United States, which was released in September. Readers familiar with this series, which includes such Pulitzer Prize-winning volumes as Daniel Walker Howe’s What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815‒1848, James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, and David M. Kennedy’s Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929‒1945, know that it offers historical synthesis of the highest order. Praising White’s “immense learning, wit, indignation, fearless judgments, and imagination,” Yale historian David W. Blight calls this newest installment “a marvelous achievement of narrative history by a great historian.”

Richard White was kind enough to answer a few questions via email this week from his office at Stanford University, where he is Margaret Byrne Professor of American History.

Library of America: In The Republic for Which It Stands, you take up the challenge of treating two periods of American history, Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, which are often written about in isolation from each other. One way you bridge the divide is by taking the Republican vision of a good society—a society of homes and “homogenous citizenship”—as an overarching theme, using it as a kind of yardstick against which to measure the age. Was the distance between governing ideology and life as it was actually lived unusually great in this period?

Richard White: Originally, the distance between ideology and life wasn’t great at all. At the end of the Civil War, the United States hadn’t yet become a nation of wage workers. Independent labor and prosperous homes seemed the inevitable outcome of a war to eliminate slavery. Large factories remained relatively rare and class divisions, although real, weren’t impenetrable. Americans believed that free labor would secure independent homes, and black homes, identical to white homes, would arise in the wake of the war. Springfield—Lincoln’s home town—embodied their hopes; the nation would become a collection of Springfields.

Similarly, a homogenous citizenry with a set of uniform rights guaranteed by the federal government in a remade republic was legislatively possible in 1865, but the ideal was never absolute. In practice Indians and Chinese would be totally, and white and black women partially, excluded.

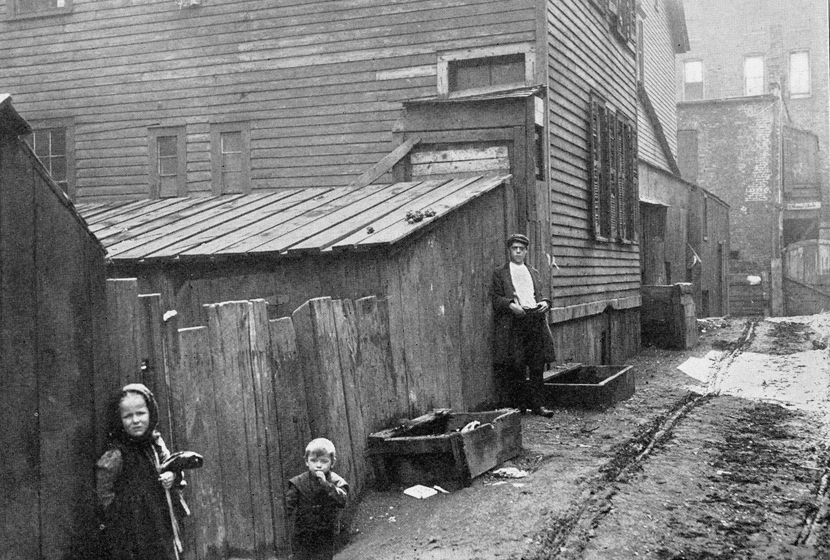

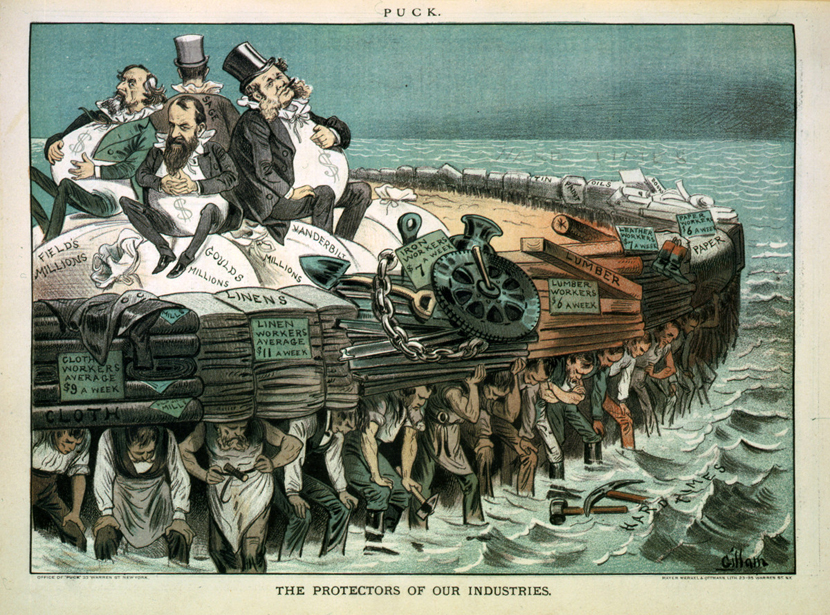

By the 1870s the gulf between the ideal and the reality had widened considerably and would continue to widen for the rest of the century. Americans listed as the markers of this failure the decline of independent labor and the rise of a large and permanent class of wage workers. The inability of many wage workers to earn enough to support the gendered ideal of a home—men protecting and supporting families, women in charge of hearth and home and nurturing children as republican citizens—proved alarming. Particularly in cities, immigrant tenements became the antithesis of the home. Not only did the federal government fail to secure black people a full and equal citizenship, but in both urban areas and the South, reformers pushed restrictions on suffrage. A kind of cultural panic, often racialized, ensued in which black people, Indians, Chinese, tramps, single working women, and many immigrants were defined as threats to the white home.

Although the economy grew immensely, the evidence we have indicates that individual well-being declined. Americans grew shorter, sicker, and the children of the poor—particularly the black and urban poor—died in shocking numbers. If the purpose of the economy was to buttress the Republic, it seemed to be failing while the two dangerous classes, the very rich and the poor, increased in numbers. The old ideal of a working life—the original American dream of a competency, the amount of money needed to support a family, provide a cushion for hard times and old age and to set children up in life, rather than great riches—seemed harder and harder to attain.

LOA: In part because historical interpretations of Reconstruction have changed so dramatically in the last 150 years, it remains one of the least understood eras in our history. And as the recent events in Charlottesville show, the meaning of the Civil War is still bitterly contested. What do you most hope readers will learn about Reconstruction from your book?

White: I would hope that they would realize that white supremacy (even though who counts as white has evolved and changed) has been a powerful and malicious force in American history. It triumphed following Reconstruction because the federal government failed to use the powers that it possessed to suppress terrorism. The failure of Reconstruction wasn’t inevitable. Terrorism won, but the Klan and other organizations could have been suppressed. The federal government and state militias did suppress terrorism in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Arkansas. Ultimately, it was the failure of the federal government to use its authority to place troops in the South and protect black voters—who demonstrated remarkable courage in attempting to retain their rights—that crippled the promise of a homogenous citizenry. Rapidly in some places, gradually in others, black men lost the vote. By 1880 John Hay thought that the Southern Democrats had so perfected their machinery of suppressing black votes “that even murder, the cheapest of all political methods in the South, will hardly be necessary this year.”

I would also hope that readers recognize that white supremacy is only one current propelling American history, and it hardly defines the American past. Reconstruction was a powerful reform movement that with the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments transformed the legal basis of the Republic over a very short period of time. It’s a reminder of how quickly change can come. Reconstruction failed, but not completely.

In the South, it’s easy to stress the inspirational ideals of Reconstruction, but these ideals need to be considered alongside its more ignoble ambitions. In my book, Greater Reconstruction includes the West as well as the South. Here homogenous citizenry included the forced assimilation of Indian peoples who existed under semi-sovereign nations. Unlike black people, they didn’t aspire to assimilate into the American nation. They succumbed to military force that deprived them of territory and tried to suppress their own governments and cultural practices.

A contrast between Southern and Western Reconstruction is instructive. The United States didn’t deploy sufficient soldiers in the South to protect freedpeople, many of whom had fought in the Union Army and virtually all of whom desired full citizenship. Instead they sent those soldiers to the West to conquer Indians who were defending their homelands. The federal government refused to redistribute the property of Southerners who’d violated their oaths of office and committed treason to loyal freedmen and poor whites, but they eagerly redistributed the property of Indians to white settlers and corporations.

LOA: One of the many ironies in your book is the fact that this period so often dismissed, in your words, as “historical flyover country,” an uninspiring age of lackluster “caretaker presidents,” in fact witnessed record levels of democratic engagement, with voter turnout in presidential elections routinely approaching a now unthinkable 80%. And this at a time when the level of economic inequality rivaled that of today. What accounts for these popular passions, and why do you think they’re missing in our own gilded age?

White: In the late nineteenth century most Americans voted out of a deep loyalty to party, but this loyalty didn’t spring from ideology. Politics functioned as an expression of identity. Republicans and Democrats were coalitions that contained factions that stretched across the political spectrum. Neither party was ideologically pure. Membership in the party depended on who you conceived yourself to be. Those who had sided with the Union, particularly those black voters who retained their rights, were overwhelmingly Republicans. Those who had sided with the Confederacy or sympathized with it were Democrats. There were crosscutting identities that modified this. Catholic immigrants in the North tended to be Democrats, in part because of a strong anti-Catholic strain in the Republican Party. Protestant immigrants were more often Republicans.

Political participation became a proclamation and celebration of communal identity. The so-called army campaigns that rallied voters in parades and mass meetings played on culture, religion, and ethnicity. Compared to the politics of identity, ideology was weak gruel. Voters turned out in startling numbers throughout this period.

By the end of the century this was beginning to change as Democrats attained ascendancy in the South and suppressed the black vote, and as Republicans in the North sought to suppress the immigrant vote. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, when it appeared that ideology and class interests were undercutting older loyalties, there was a general movement among the more privileged classes to turn against democracy and restrain it. After the Great Strike of 1877, Charles Eliot Norton of Harvard, one of the leading liberal intellectuals, considered universal suffrage a mistake. He thought the “untaught classes” were in “wide-spread revolt against civilization.”

One reason that we don’t have political participation today on the level of the first Gilded Age is because so many of the attempts to restrain voting have succeeded. Even after the worst abuses—poll taxes, the grandfather clause in the South, etc.—have been removed, voters still face onerous rules for registration, residence, and proof of identity. Recent court cases demonstrate the perseverance of such restrictions. We shouldn’t wonder that voting declines when there are so many active attempts to suppress the vote.

Identity politics has hardly vanished, but many voters find it harder to match those identities to a political party. As partisan loyalties decline and independent voters increase, it’s harder to mobilize the vote.

LOA: William Dean Howells, the great champion of literary realism (represented by two volumes in the Library of America series), emerges as a central voice in your book. What drew you to him, and how well do his novels serve as a portrait of the age?

White: Reconstruction and the Gilded Age together form such a sprawling, contentious, and diverse period that I needed a figure—a surrogate narrative voice—that would persist throughout the era and try to make sense of the overwhelming and rapid change taking place. As one of my colleagues put it, I needed a Dilbert.

Howells is my Dilbert and much more. He was remarkably well connected in political, literary, and broader cultural circles. He was a Republican who grew disgruntled with the Republican Party. He was a nineteenth-century liberal who started out believing in laissez-faire, small government, and the gold standard and realized that his ideological beliefs could make no sense of the world emerging around him. He recognized the era’s failures and injustices, but he could never really decide what to do about them.

In his novels—he was one of the era’s leading literary realists—his magazine columns, and his letters he thought deeply about the world he lived in and about the place of himself and his family within it. He, like all of us, could be deeply flawed with terrible blind spots (for instance the treatment of Indians and women), but he was also thoughtful, self-critical, and articulate. He enunciated the struggles of the age, recognizing how different the nation that was emerging was from the nation that the Civil War generation had expected to create.

Richard White is Margaret Byrne Professor of American History at Stanford University and the author of numerous prize-winning books, including Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America; The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650‒1815; and “It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own”: A New History of the American West. He is a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Mellon Distinguished Scholar Award, among other honors.