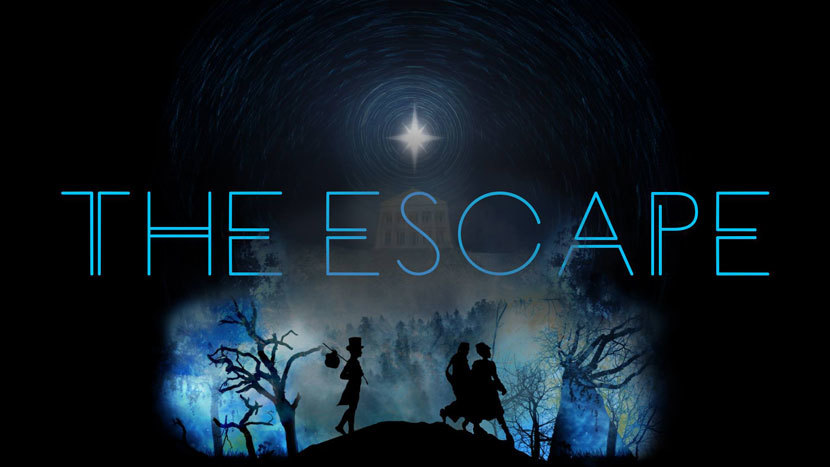

A rare opportunity to see an American theatrical landmark comes to life this week when the Columbia School of the Arts presents a fully-staged production of William Wells Brown’s play The Escape; or, a Leap for Freedom for five performances between February 14 and 17.

Considered the first published play by an African American, The Escape is a five-act comic melodrama centered on two Missouri slaves who secretly marry before making a desperate bid for freedom. Brown had it printed as a pamphlet in Boston in 1858; though the work was never produced theatrically in his lifetime, he performed excerpts from it at abolitionist rallies and other public events at which audiences were said to roar with laughter. In his 2014 biography of Brown, Ezra Greenspan (the editor of Library of America’s Brown edition) writes that The Escape is marked by “superior imaginative complexity, social commentary, and personal investment,” and “has the distinctive iconoclasm of Brown’s zaniest work.”

The Columbia School of the Arts staging of The Escape is the passion project of Columbia MFA Directing Candidate 2018 Mark H, whose enthusiastic advocacy makes it clear that Brown’s play is seriously overdue for a fresh assessment. Along with two members of his cast, he responded to Library of America’s questions via email.

| READ THE PLAY |

|

| in William Wells Brown: Clotel & Other Writings |

Library of America: Brown published The Escape in 1858 but apparently its first fully-staged production wasn’t until 1971, and even today it’s somewhat obscure. What drew you to the work, and how are you going to make it speak to a contemporary audience?

Mark H: I was first drawn to the work simply for its historical and cultural significance. I consider myself not only a theater director, but also a theater scholar. I, too, am an African American man madly in love with, and invested in preserving and expanding, African American cultural heritage. Part of my work as a theater director and educator is in developing a philosophy, an aesthetic, and a practice that is uniquely African American, and uniquely my own. There is no better way to do this than to mine the richness of the past, and no better place to begin than the beginning.

It was a few years ago when, as I was reviewing my copy of A History of African American Theatre, by Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch, I came across the name William Wells Brown, and his play The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom. It wasn’t until a little over a year ago, however, as I was considering ideas for my MFA thesis project at Columbia University, that I finally sat down to read it.

The play is a miracle—funny, tragic, beautiful, and complicated. Just like America, then and now. It was written in a period in which many of our current institutions were newly forming and solidifying, and many of the larger issues facing American society then are still alive and well today. Despite this year marking the 160th anniversary since it was first published, this play still feels vital, fresh, and totally relevant.

The one full production of this play on historical record that you mention just so happened to be directed by one of my earliest theater mentors, James “Jim” Spruill, whom I had the fortune of studying with as an undergraduate at Boston University. He was a man and teacher that I truly admired and respected. It makes so much sense that he would have discovered this play and seen how truly special it is, and it feels so right to be following in his footsteps, directing what may be only the second-ever production.

LOA: Judged strictly by the text, a comic character like Cato, a slave with medical training, could be uncomfortable for a modern audience—he regularly refers to his “ole massa,” mentions wanting to look “suspectable” (meaning respectable), and so on. How are you handling these and other parts of the play that have an aspect of minstrel show about them?

Mark H: By the time William Wells Brown wrote The Escape, blackface minstrelsy had already become America’s first truly unique form of popular entertainment, and it has had a profound influence on American entertainment since. It’s a form of theater as complicated as America itself, and it’s important that we reckon with it, that we pull lessons from it, and not ignore it. In writing the character of Cato, Brown is referencing the minstrel tradition through what would have been in his time a very well-known and popular archetype from that genre. Cato provides a steep challenge for any performer, as well as an amazing opportunity for virtuosity.

What I find so fascinating about Cato, and about this whole play, is that Brown simultaneously honors, critiques, and subverts the various genres that influenced him—namely Shakespeare, melodrama, and blackface minstrelsy—as well as American culture in general. Cato shucks, jives, and grins in the presence of “ole massa,” but we very quickly learn just how extremely WOKE he is, how nimbly he can navigate any situation, and how deeply passionate and sensitive he is. This is a character of extreme dignity and pride, with a clear vision of the man he would like to be, and he is always prepared to seize on any opportunity to become that. Cato is a character ahead of his time, and one that a 2018 audience will really connect with.

To me, The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom at its core celebrates the triumph of freedom over those forces that seek to destroy it, and the achievement of the imagined self. This is the perspective from which I’ve approached the play, and I believe that despite any uncomfortable moments, and there are some incredible ones, this spirit of celebration is what will be most resonant in the minds of the audience as they exit the theater.

LOA: At the same time, the romantic leads Glen and Melinda often speak in an elevated diction that might come across as over the top in a present-day performance. How are you, and the actors playing Glen and Melinda, approaching these passages?

Mark H: Oh, don’t get me started on Glen and Melinda. Their speeches are some of the most beautiful moments in the play, and the language is stunning. Where Cato is a reference to the minstrel tradition, Glen and Melinda were clearly inspired by Shakespeare, whose work was extremely popular in America at the time. Shakespeare even holds an important place in the African American theater tradition, as the very first production of the very first black theater company in America (The African Theatre) was of Shakespeare’s Richard III. Glen and Melinda are the young lovers, our Romeo and Juliet, and we root for them.

Poetry is capable of expressing a heightened reality, and I can’t think of many situations more heightened than the high of deep romantic love, or the crushing despair of enslavement. The characters’ heightened poetic language reflects the attempt to capture through words what’s really beyond description, beyond language. In anticipation of moments when verbal language isn’t so clear, or is inadequate, I’ve worked a lot with the actors to make sure that their own understanding of the language isn’t just cerebral, but is understood in their bodies, that they experience the language physically.

Aisha Carpenter (Melinda): I think the best, and quite frankly only way to approach elevated, “over the top” diction is with patience. When it comes to the two lovers, it’s almost as if William Wells Brown wrote this play, then plucked Glen and Melinda from another play or piece of writing and dropped them into the mix of The Escape. No one else in the piece speaks, thinks, or acts the way they do. I think that because of this, their way of speaking not only needs to be acknowledged but emphasized and honored.

Brown wrote this language for a reason, and we may never know what that reason may be, but, my father always used to tell me, “Knowledge is Power.” And what that means to me is anyone can take away anything from you except what you know. Slaves couldn’t read or write. The thought or tiniest inkling of them doing so could have resulted in torture or death. When assimilation and colonization destroyed the African tongue of the American slave, they were left with language more similar to that of Cato or Hannah [another character]. That uneducated tongue is part of what made a slave sub-human, and animalistic. The fact that Glen and Melinda have the incredible power of their thoughts, words, and knowledge makes them strong. The fact that their thoughts and words are so elevated and over the top makes them that much stronger.

David L. Glover (Glen): After my first reading of the script there were clear indicators that the language in the play was profoundly deliberate and that the text ascribed to Glen and Melinda was influenced by Shakespeare. Every character is a custom job, and it was highly useful to have a set of principles for deconstructing Shakespeare’s language available in unpacking Glen’s language. Being a poet myself and having a personal passion for Shakespeare’s plays helps a lot, in the sense that I take a great deal of pride in the work required to bring forth non-colloquial text as clearly and effectively as possible. So, in unpacking the language I navigate the text through as many ways as possible. First, I research every word. Language evolves, it’s never a sure shot that what a word means today is what it meant fifty years ago or when it was originally derived. In fact, I’ve found that it usually doesn’t mean what I originally thought it meant. So research is key.

One example of embracing the text as my own is an exercise in which I had to physicalize every word in one of Glen’s soliloquies. It forced me to quite literally feel what the words do to my body, and imbued each word with a tangible, physical sense of meaning that’s personal to me. It told me that Glen’s spirit is aching, and that words aren’t always enough.

LOA: The musical interludes Brown included in The Escape are important in the original context because he took popular minstrel numbers and transformed them into abolitionist anthems. Can you tell us a little about what your Music Director (Jerome Brooks, Jr.) and composer (Nolan Williams, Jr.) will do with the songs for your production?

Mark H: When I first met with the creative team, I expressed that I was more interested in capturing the spirit of mid-nineteenth-century America than attempting to recreate it. I asked the team to look for the principles underlying art and design at the time. If clothes of the time were designed to be modest, then it was important that the costumes in this production reflected that. So with that we’ve given ourselves the flexibility of pulling from many different sources, as long as the sum of all the parts capture, as closely as we can, our understanding of the spirit of the period.

This applies to the music as well. As you mentioned, almost all the songs in the play are set to classic minstrel tunes with lyrics that have been refashioned to turn the songs into political anthems. I think this is brilliant on Brown’s part. The tunes indicated in the play would have been recognizable to the audiences of the time, but not so much to a contemporary audience.

One directorial choice might have been to use music recognizable to a modern audience, music that might highlight the critique inherent in Brown’s lyrics, just as he intended. However, because music is so closely linked to historical context, and we set out to keep the feel of the period, it felt like a better choice to use the original melodies as a base from which to let our creativity fly. Our fantastic music director, Jerome Brooks, Jr., created some wonderful new arrangements, and added a few surprises that I think greatly serve the play—and flat-out rock!

There is one song where no melody or other musical reference is indicated in the script—Glen’s musical ode to the North Star, that cosmic symbol of freedom and hope that helped guide thousands to freedom. This song is a real turning moment in the play, and our composer Nolan Williams, Jr., CEO of NEWorks Productions, has created a stunning composition for us that has both a classic folk and gospel feel to it. The songs, performed by our actors, accompanied by our live band, are some of the most memorable moments in the entire production.

Official Facebook page for The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom at Columbia Stages