Exactly fifty years ago, on the night of January 30–31, 1968, one of the crucial battles of the Vietnam War broke out as almost ten thousand North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong soldiers launched a surprise attack on Huế, the third-largest city in Vietnam and its former capital.

The assault on Huế was part of the Tet Offensive, a series of coordinated Communist attacks on more than 100 cities and towns throughout South Vietnam that led to some of the most intense fighting of the war. (The offensive took its name from Tet, the Vietnamese word for Lunar New Year, which fell on January 30.) American and South Vietnamese forces retook the city after twenty-six days, but at a terrible cost in human life and material destruction. As with the larger Tet Offensive, the outcome was widely perceived as a Communist military failure that led to an unexpected political victory. Although the Tet attacks failed to start popular uprisings against the Saigon government and cost the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong as many as 40,000 killed, the unexpected ferocity and extent of the fighting turned American public opinion against the Johnson administration’s open-ended pursuit of military victory. The title of Mark Bowden’s new history of the battle is Huế 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2017), and in yesterday’s New York Times, historian Max Boot writes that in the wake of Tet, “The American quest for victory in Vietnam was over; the only question now was the pace of disengagement.”

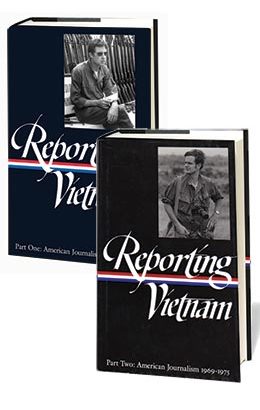

|

| Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959-1975 |

Several pieces collected in Library of America’s two-volume anthology Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959-1975 offer contemporary reporting about the Battle of Huế. Historian Geoffrey C. Ward, who wrote last fall’s eighteen-hour documentary The Vietnam War, recently called Reporting Vietnam “an astonishingly polished first draft of history.” The publication of Bowden’s book presents an opportunity to revisit that first draft from the perspective of a half-century later.

In Huế 1968, Bowden refers to Don Oberdorfer of The Washington Post as “the definitive chronicler of the Tet Offensive.” Reporting Vietnam includes an excerpt from Oberdorfer’s 1971 book Tet! describing the meticulous, months-long planning by the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong for the offensive, and how the poorly coordinated U.S. and South Vietnamese intelligence services were caught off-guard by the attack on Huế. Oberdorfer also includes graphic testimony about the widespread “purges” (i.e., executions) the Viet Cong conducted against the local civilian population.

Michael Herr offers a more personal account of Huế in the famous “Hell Sucks” episode from Dispatches (1977), his classic impressionistic account of covering the war as a correspondent for Esquire. In Herr’s vivid telling, the battle is a waking nightmare:

It was cold and the sun never came out once, but the rain did things to the corpses that were worse in their way than anything the sun could have done. […] On the worst days, no one expected to get through it alive. A despair set in among members of the battalion that the older ones, the veterans of two other wars, had never seen before. Once or twice, when the men from Graves Registration took the personal effects from the packs and pockets of dead Marines, they found letters from home that had been delivered days before and were still unopened.

About the Tet Offensive, Herr wrote: “We took a huge collective nervous breakdown [. . .] instead of losing the war in little pieces over years we lost it fast in under a week.” Assessing the enduring influence of Dispatches, Bowden, looking back, asserts that over time Herr “would probably do more than any other writer to frame the story for American readers—the story not just of Huế, but of the whole war.”

Reporting Vietnam also includes CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite’s closing commentary from the special report the network aired on February 27, 1968, in which the veteran newsman—increasingly mistrustful of the official government line—reported on his firsthand impressions from his visit to Vietnam a few days earlier. Bowden writes: “He had seen enough to be convinced he had not been told the truth.” Cronkite ended by telling viewers, “To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion,” and recommended that the United States pursue a negotiated end to the war.

In the Epilogue to his book, Bowden calls the reporting done from Huế “a vital public service” and concludes:

Journalism has long been blamed for losing the war, but the American reporting from Huế was more accurate than official accounts, deeply respectful, and uniformly sympathetic to U.S. fighting men.