Ursula K. Le Guin died at her home in Portland, Oregon, on Monday, January 22 at the age of 88. Her career as novelist, poet, essayist, translator, and children’s book author spanned more than half a century, and earned her five Nebulas, five Hugos, and the National Book Award for children’s literature, among many other honors. In 2014 she was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. As Max Rudin, Library of America’s president and publisher, said in 2016, “Ursula Le Guin’s writing has reconceived the literary aspirations, and redefined the expressive possibilities, of every genre she’s touched.”

Library of America publishes three collections of her fiction: The Complete Orsinia, Hainish Novels and Stories, Volume One, and Hainish Novels and Stories, Volume Two. For Stefanie Peters, Le Guin’s editor at Library of America, “The opportunity to work with Ursula, whose wit was as large as her generosity, was an enormous joy and honor. She was incredibly engaged in the process, unearthing material from her attic for us to use, and happily allowing me to quiz her about everything from textual issues to how accents work in the Orsinian language. As a woman and as a titan of American literature she is and will remain a lodestar.”

To commemorate Le Guin’s life and legacy, Library of America reached out to some of her fellow writers. Their responses appear below, in the order in which we received them.

Brian Attebery • Harold Augenbraum • Harold Bloom • Michael Chabon • Karen Joy Fowler • Neil Gaiman • Kathleen Ann Goonan • Nalo Hopkinson • Jonathan Lethem • China Miéville • Joyce Carol Oates • Ada Palmer • Julie Phillips • Elaine Showalter • Zadie Smith • Jo Walton • Gary K. Wolfe • Lisa Yaszek

Zadie Smith

Ursula Le Guin was able to reimagine many concepts we take to be natural, shared, and unalterable—gender, utopia, creation, war, family, the city, the country—and reveal the all-too-human constructions at their center. (She also deconstructed the idea of the “center.”) She took nothing for granted, interrogated everything. That these gifts—more common to philosophers and scientists—should have appeared in a writer was wonder enough. But on top of that there were her sentences, as elegant and beautiful as any written in the twentieth century. And then she extended herself into the twenty-first—and taught us a few things, too. I’ll miss her. Literature will miss her. There’s no one like her.

Back to top

Michael Chabon

I don’t know what to say about the passing of the greatest American writer of her generation except that from the time I was nine years old, continuously, her work deepened, expanded and challenged my expectations of literature, awed me with the power of an unfettered imagination, and obliged me to sympathize with and understand—and in some stunning measure belong to—cultures and societies far removed in space, time, and even biology from my own. Toward the end of her long life Ursula and I became friends, of a sort, which only makes the blow of her loss that much harder to bear.

Back to top

Neil Gaiman

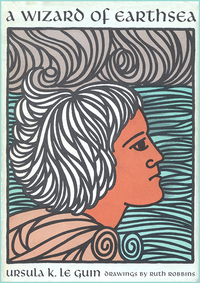

I discovered Ursula with The Left Hand of Darkness and with the Earthsea trilogy, both when I was about eleven. The first of the books opened my head and made me view gender differently—not as something fixed, nor even as something important, but as something mutable and less pertinent than what kind of person you are; the trilogy made me look at the world in a new way, imbued everything with a magic that was so much deeper than the magic I’d encountered before then. This was a magic of words, a magic of true speaking.

I read everything I could by her, after that. Her essays on writing changed me as a young writer, made me see the craft more seriously and made me try always to remember the joy in it.

I was honored to have been able to present her with the National Book Awards’ Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, in 2014. I wrote to her, then, and said:

You have no idea how nervous I am at the idea of writing to you. You’ve been one of my heroes since I bought A Wizard of Earthsea with my pocket money at the age of 11. Your SF shaped my head as a teenager, and told me that anything was possible and that events occur in context. Your essays on writing shaped me as a writer (something that occurs to me every time the train home passes through Poughkeepsie), and your later essays made me begin to think of myself as a feminist, and to change the way that I thought about men, about women, about language, about stories, about abortion.

I asked if there was anything she wanted me to mention in my introduction. Her reply told me that age hadn’t softened her a bit. She said:

Having sat through five-minute thankyou speeches that seemed to last three hours, I thought I’d enliven the gratitude with some very brief remarks about (for one thing) the big publishers’ practice of grossly overcharging public libraries for ebooks, limiting access, etc. I know you’re a true library lion. So I wanted to check if you’d welcome this, & if so we could maybe kind of strike the same note—or at least tell you, so that if I do say some things that our publishers will perceive as ungrateful, subversive, unladylike, etc., it won’t take you by surprise.

And she made a speech about publishers and about Amazon that only someone in her position could have said. I’m so glad I was there, and so glad I was alive and reading books when she was writing them.

Back to top

Jonathan Lethem

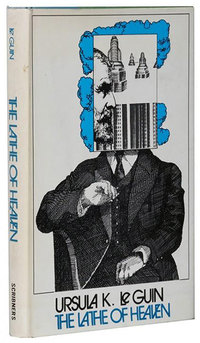

Like nearly any other reader of my generation, I was awed by early encounters with Ursula Le Guin’s writing—in my case, The Dispossessed, The Word for World Is Forest, and The Lathe of Heaven, as well as a short story I still teach, “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.” I wouldn’t claim a direct “influence” from her work; that word doesn’t describe the exact angle at which her writing entered into my own attempts. Instead, Le Guin set a very high standard, implicit in every word she wrote, and it was that standard—of grace, intelligence, precision—that pushed me.

In the ’90s I had the luck of knowing Ursula. I suppose that in a mild way I was “taken up” by her. It began with a postcard, out of nowhere, it seemed to me, in which she expressed her fondness for a story I’d written, which she’d encountered while judging the James Tiptree Award. Shortly after that I was invited to a lunch at her country house, along with Carter Scholz, Karen Joy Fowler, and Kim Stanley Robinson. I was by far the youngest there, and the least-published. Driving there with the other guests, the day was already a heady one for me before we’d arrived at the lunch, which Ursula and Charles had laid out on a long table in an orchard. The scene was like something out of a Bergman film (one of the happy ones). There were flowers, the slow unveiling of all sorts of good food, and embracing conversation which beguiled me into thinking I’d entered into the enchanted circle of a writer’s real life, at last. (Nope.)

I remember another evening, in Berkeley, where we had dinner at a Thai restaurant with the SF writer Poul Anderson. I can’t recall the circumstances leading to this, but I’m embarrassed to remember that I held myself above him, in some way, not for his genre identification but for his association with a kind of reactionary Libertarian strain which, in my thinking, divided that literary field utterly between writers like Le Guin and writers like Anderson. For Ursula, it wasn’t so simple. She treated Anderson, a tall shy brainiac type, as a fellow storyteller and student of culture, a bearer of unique forms of wisdom. So, the conversation was as extraordinary as it had been in her country orchard. Here was Ursula Le Guin’s gentle standard, again, pushing me in person as it had in her writing.

She also taught me, long after I should have known, to say the word “Diplodocus” correctly.

Back to top

Watch: Ursula K. Le Guin’s remarks at the 2014 National Book Awards (6:09)

Ada Palmer

Like many authors, I have a fat folder of rejection letters. Over years as I added to the folder leaf by disappointing leaf, I kept inside a printout of Ursula Le Guin sharing a rejection she received for The Left Hand of Darkness, with her note, “This is included to cheer up anybody who just got a rejection letter. Hang in there!” It helped so much, and in a thousand moments like that she was not just a brilliant author, but a custodian of young writers, and of the field.

In 2014, when I had (finally!) sold my books to Tor and was waiting breathless for the big day, I spent half an hour rewatching her breathtaking National Book Awards speech. And crying. I wrote to her, and thanked her for synthesizing so potently how invaluable F&SF literature is, not as escapism or passive entertainment, but as a creative, boundary-pushing force that widens perspectives and galvanizes social change. And I told her how it helped me finally articulate my fears about what is happening to book publishing now. My first series is oddball, difficult, hard to describe, so hard to sell. It’s been a success but I was incredibly fortunate to find an editor so excited by the ideas that he was willing to gamble on it. And it’s getting harder for editors to take those risks as publishers are increasingly battered by aggressive, profiteering forces. Her speech reminded us of what aspiring writers rarely understand, that publishing is a partnership, that agents and editors help us reach bookshelves and podiums, and that new authors will never reach them if editors are no longer free. As I wrote to her then, “I don’t want to be part of a small, last generation of F&SF authors published by bold publishers who love the genre and what it can do for the world. I don’t want my voice to enter the conversation only to be followed by an era of the clipped-winged works monopoly produces. You helped me realize that we—readers, authors, people—have the power to stop that if we try.”

She wrote back, that to me the most amazing part, this incredible author living in a whirlwind of deadlines and requests wrote back to an unknown not-yet-published author, because she was a custodian of literature, and always took the time to reach down and give others a leg up. To pay it forward. And her reply began with words I never expected to hear from such a towering figure. She said, “I really thought nobody would pay attention. The response has been strong, and heartening. Reminds me that it is always worthwhile speaking out, even when it is a bit scary and seems useless. Write in freedom! Ursula Le Guin.” Well, we paid attention, and we always will. Thank you.

Back to top

Jo Walton

When I went to Shakespeare’s grave in Stratford, I thought how strange it was that he was dead in the church when he was still alive in the theater. I feel the same about Ursula K. Le Guin. Even as I’m shocked and sad to hear of her death, I know that her books are still alive. It’s impossible to overstate the quality and significance of her writing, which means so much to me personally not just as a writer but as a human being, that I don’t think I’d be the same person without it. She changed science fiction, she opened it up, she widened the possibilities of what we can do with it. I can’t mourn her loss as a writer, because that isn’t gone. In the day since her death I’ve seen so many writers talking about her influence, writers at the top of the field, newly emerging writers, everyone. But she’s gone as a person. She has left the conversation. She kept on writing with clear eyes and a sharp tongue, she was so alive and vital and passionately involved in everything right up to the end. She is exemplary in so many ways. Her work persists, her influence persists, but I’ll miss her all the same. We’ll never know now what she would have made of tomorrow. It’s up to us to carry her fire forward.

Back to top

Harold Bloom

I knew Ursula Le Guin only through our extensive exchange of emails. We became friends who discussed her work and mine and her darkening views of our nation and indeed of our world. I encouraged her to write more poems as I believe they have been undervalued. Our mutual health problems necessarily were a part of our discourse. She was half a year older than I was, and both our marriages had gone past sixty years. Though I worried about her condition, I was unhappily shocked when she departed two days ago. I had sent her a last email yesterday, not knowing that she was gone. I learned a great deal of wisdom from our exchanges as I had from her novels, poems, and other writings. Ursula was a seer and what she called a Foreteller.

Ursula was an exquisite stylist. Every word was exactly in place and every sentence or line had resonance. She was a visionary who set herself against all brutality, discrimination, and exploitation. Her religion was the Tao, in a personal interpretation. We discussed it but I never quite understood its dimensions. I am hardly unique in feeling bereft. Many thousands of readers have been moved by her to a richer sense of life.

So many of my old friends have died recently that Ursula was a blessed new person in my existence. I will go on missing her until I end.

Back to top

Elaine Showalter

In 1986, giving the Commencement address at Bryn Mawr College, Ursula Le Guin drew a distinction between the Father Tongue, the language of power and reason all women who wanted a public voice had to speak; and the Mother Tongue, the language of stories, conversation, and relationship. In her conclusion, she told the students that women are “volcanoes. When we offer our experience as our truth, as human truth, all the maps change.” And she implored them to speak with a woman’s tongue, to erupt. “If we don’t tell our truth, who will? Who’ll speak for my children and yours?” Le Guin was a great artist and a noble person despite never winning the Nobel, and set the pace as a writer for women unlearning silence, fear, and self-doubt. Now she belongs to the ages.

Back to top

Harold Augenbraum

In 2014, when I was the Executive Director of the National Book Foundation, the Foundation’s Board of Directors voted to offer its Award for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters to Ursula K. Le Guin. Ursula had had an uncomfortable relationship with the National Book Awards. Several years before, she had responded to my request for a nomination of the best National Book Award winners in Fiction by stating, graciously, that she did not always agree with the Foundation’s approach and would prefer not to take part in such a poll. When several years later I called and asked if she would be willing to accept the lifetime achievement award, she reminded me of her uneasy relationship to the Foundation, said she didn’t travel much, would think about it, and would get back to me the following day, which she did. A few months later she came to New York for the ceremony. Neil Gaiman introduced her. She adjusted the microphone downward, and proceeded to speak truth to power, praising writers and lambasting the assembled publishing industry for putting profits before art, interrupted only by applause and audience member Jackie Woodson’s shouting “We love you, Ursula!” In the following three weeks, 250,000 people viewed her speech on YouTube. Ursula was a great writer and a powerful presence, always thoughtful and gracious.

Back to top

Joyce Carol Oates

Ursula Le Guin is one of the great American writers and a visionary artist whose work will long endure. We will miss her luminous presence and her outspoken sense of justice, decency, and common sense.

Back to top

Brian Attebery

Wherever I go as a scholar, as a teacher, as a person, I find that Ursula K. Le Guin was there first. By now it’s a habit that as I struggle toward some new discovery about narrative or gender or justice, I check through my collection of Le Guin stories and essays and, sure enough, she was thinking about the same thing twenty years earlier, with more acuteness and imagination than I could hope for. It has also been my habit, for the past four decades, to run ideas past Ursula herself in a letter or an email or a phone call. She always responded, and her response always helped me understand what I was struggling with. As many can testify, she was amazingly generous with her time and attention, willing to act as cheerleader or sympathetic ear or tough critic for innumerable young writers and scholars. She was mentor to more than one generation, with the result that contemporary literature is a whole lot more interesting than that of the mid-twentieth century. She invented us: science fiction and fantasy critics like me but also poets and essayists and picture book writers and novelists from Karen Joy Fowler to David Mitchell: just about anyone whose work looks past the here-and-now.

I had the incredible privilege of receiving some of my Le Guin mentorship in person, and so I have her own warm, humorous, mesmerizing voice in my ears when I read her words. But anyone can read those words: thank the universe that she wrote prolifically and brilliantly on so many subjects and in so many forms. The voice is there, whether or not a reader ever heard it firsthand. And the wisdom is still there, still twenty years ahead of the rest of us. Some of that wisdom concerns death. I will be rereading some of Le Guin’s fiction and poetry looking for understanding and consolation over the next months, especially the Earthsea stories. In The Farthest Shore, Ged speaks, mentor to pupil, about life and death. He says to Prince Arren, “Look at this land; look about you. This is your kingdom, the kingdom of life. This is your immortality. Look at the hills, the mortal hills. They do not endure forever. The hills with the living grass on them, and the streams of water running. . . .” I will try to think of Ursula walking here in that kingdom of mortality with us, although she has also gone ahead, leading the way, as she has always done.

Back to top

China Miéville

We mourn the incomparable Ursula Le Guin, and it hurts.

A writer of intense ethical seriousness and intelligence, of wit and fury, of radical politics, of subtlety, of freedom and yearning, Le Guin was a literary colossus.

Let us remember her as that, rather than, in the title of an obituary in one major newspaper, a “grande dame of science fiction.” Not that she needs “rescuing” from the genre she never hesitated to defend: the label is not wrong, but inadequate. Le Guin was impatient, and rightly, at those who, as she put it, “stick me into that one box, while I really live in several boxes.” And, more importantly, “grande dame?” It’s hard to imagine someone so acutely and acidly attuned as she was to sexism, and the particular slights against old women, letting such gendered and ageist condescension pass. And the primness implied in the designation is a particular insult to one so endlessly curious, one who never stopped listening to and learning from the readers to whom she gave so much. It was in part out of such conversations that Le Guin repeatedly revisited her own seminal work, with an open-mindedness that was humbling, and unique in modern letters.

There has never been a writer more generous than Ursula Le Guin. She wrote for our own better selves.

Back to top

Karen Joy Fowler

One of my favorite Le Guin books is the little noticed Changing Planes, and my favorite story in that book is “Seasons of the Ansarac.” Sometimes you read a Le Guin story and you can’t imagine where it came from; the imagination that produced it remains awesome and inexplicable. But sometimes she helps you out, telling you that Omelas is Salem O backwards or that “Seasons of the Ansarac,” in which she details the lives and migrations of an alien people, was inspired by what we know about the lives of our earth-dwelling ospreys.

I mention this in the hope that everyone will go read that book, but also because birds figure in so many of my memories of Ursula. She noticed birds, really saw them, listened to them. She noticed the natural world in a way I worry we may have lost, we, who live indoors, glued to our screens and devices. One of the last times I saw Ursula, she and Molly Gloss took me to Sauvie Island to see the sandhill cranes. They pointed out the pairings. Ursula imitated the purring call so I would know what I was hearing.

There are so many things to say about Ursula, but I don’t want this one to get lost—how often and how beautifully she gave voice to our fellow animals, in all their unknowable mystery. She never took sides or got sentimental; she was a great cat lover—those adorable killing machines. But she gave every creature the courtesy of her attention and curiosity. And how many other authors have tried to write a story in the voice of a tree? Much less pulled it off?

Back to top

Gary K. Wolfe

Ursula K. Le Guin was already an intimidating figure, regarded by many as the best science fiction writer in the world, when I first met her at an academic conference in the late 1970s. She had published her original Earthsea trilogy, The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed, and The Word for World Is Forest, as well as several now-classic short stories including “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” which later turned out to be possibly the most successful story I would ever teach in my college classes. So even back then it took a couple of deep breaths to get up the nerve to actually speak to her.

In person, though, she was anything but intimidating—brilliant and sharp-witted, to be sure, but also quick to laugh, deeply attentive, and politely willing to engage with the half-baked literary theories of a junior professor. We only met a handful of times over the next few decades, sometimes on conference panels, once on a podcast, a couple of times for group meals. And each time, it seems, she had just written something that further extended the possibilities of the kind of fiction she loved, which was unabashedly and unapologetically the fiction of the fantastic: the remarkable multimedia Always Coming Home, the later stories which revisited and interrogated her own earlier work about Earthsea or the Hainish worlds, the comic-absurd stories of Changing Planes, the moving (and thoroughly nonfantastic) chronicle of the generations of women in a small Oregon town, Searoad, and, late in her career, the remarkable feminist revisioning of the Aeneid in Lavinia.

Her influence is impossible to catalogue, and—rather amazingly—even those earlier novels and stories never lose their freshness. New generations still learn unexpected ways of thinking about gender from The Left Hand of Darkness, or more complex ways of thinking about utopia and dystopia from The Dispossessed. Her work has become a staple of college classes, but perhaps more impressive is the number of readers who find her work entirely on their own, or through the recommendations of friends, or from learning that their own favorite authors built their careers quite consciously in Le Guin’s wake. For a writer who usually avoided didacticism in her own work, even when dealing with the most complex ideas, she seems to have taught us all.

Back to top

Julie Phillips

I first met Ursula when I was a freshman in college and she came to give a poetry reading. The next day, she had agreed to meet with a group of interested students. Although she inspired devotion in her fans, she wasn’t the household name she later became, and the group was small. We were the same age as her own children. We sat on the floor around her chair and asked her questions, which she answered in a deep, musical voice. She projected authority but invited conversation. I had recently noticed something about her books that bothered me, so I gathered my courage, put my hand up, and said, “Why are there so few women characters in your Earthsea books? Why do only men do magic?”

She’d been asked that question countless times by 1983, but if she was impatient she didn’t let it show. She said, “All the fantasy stories I had read, all the models I had, were about men. I didn’t know how to write a fantasy about a woman character.” My question was callow. Her answer surprised me and gave me a new perspective. In conversation and in her work, Ursula has been surprising me and widening my field of vision ever since.

Several years after that session with us kids, she went back to Earthsea and rewrote it from the point of view, not only of a wizard and a king, but of a housewife and a child who is also a dragon. Few other writers would have had that courage, but freedom was something she valued above all, including the freedom to change.

At the end of her last Earthsea novel, The Other Wind, she broke down the low wall of stones that separated the living from the unchanging land of the dead, so that death could be part of life again. The pulling apart of the stones brought tears to my eyes when I first read it, and every time since. As Brian Attebery said this week, Ursula taught us in many different ways to accept death. What she couldn’t do for us was make it easier.

Back to top

Nalo Hopkinson

Ursula, I’ll always remember your mischievous smile when I told you at a convention that I’d been too shy to come up and talk to you, and you replied, “Silly girl.” I loved it when I’d read a simple, compassionate, beautifully-wrought sentence in a work of yours and find myself in tears without exactly knowing why. I loved it that you didn’t suffer fools gladly. I’m in tears again at the news that you’re gone. This time, I know exactly why. Thank you for what you brought to the world.

Back to top

Lisa Yaszek

Science fiction lost one of its true legends with the passing of Ursula K. Le Guin. This is a particularly sad event because we’ve lost not just one of our most gifted and imaginative visionaries, but one of our community’s best citizens as well. Le Guin’s work first gained attention in the 1960s and early 1970s, an era when other writers of literary science fiction—Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, and Margaret Atwood—were carefully distancing themselves from genre fiction to maximize book sales. By way of contrast, Le Guin always remained firmly entrenched in her chosen genre, exploring its edges and pushing its boundaries in her fiction while using nonfiction essays and other means of public expression to explain the meaning and value of science fiction to non-genre readers. She was truly one of our best ambassadors to the mundane world.

Le Guin was also incredibly gracious with her time and energy in the science fiction community itself. I had the pleasure of first meeting Le Guin as a graduate student working at WisCon in the late 1990s. Her willingness to reach out and share a breakfast with a student she had never met before touched me deeply; it was one of those pivotal events that made me realize, yes, I really do want to be part of this world. I had a similar experience more recently when Le Guin agreed to blurb one of my forthcoming books—and then went above and beyond the call of duty by editing and fact-checking parts of the book for me as well. I was honored—Ursula K. Le Guin was literally helping me make (feminist science fiction) history! Once again, I was struck by how fortunate I am to be part of a literary community where the boundaries between author, scholar, and fan are so permeable, and where brave people so often act just like the heroes they write about, putting aside their differences and working together to build new and better futures for all. And so, thank you, Ursula K. Le Guin, for all you’ve done for those of us left here on Earth. I hope you are having a wonderful adventure among the stars.

Back to top

Kathleen Ann Goonan

Ursula Le Guin was one of the most influential American writers of the past fifty years. She wrote from her own strong place, her mind, character, and interests fostered by an academic anthropologically-focused family that valued vanishing cultures. It seems inevitable that she too would explore culture and diversity in a brilliant oeuvre owing allegiance to no particular genre, although the field of science fiction, which welcomes brilliant idiosyncratic explorations of what makes us human, gave her resounding ovations early in her career, as did the National Book Foundation late in her career when it bestowed on her its Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

It may come as a surprise to those who do not read science fiction to learn that its focus is relationships. Our relationship with technology might first spring to mind as that most strongly defining SF. Le Guin pioneered the shift toward understanding that the exploration of relationships among ourselves wherever they manifest—politics, gender issues, or in the other/alien/enemy Walt Kelly pointed out is us—is a literary act to which the marvelously elusive boundaries of science fiction are powerfully suited.

And then there is, of course, our relationship with the astonishing spectrum of our fellow-travelers, and myth. Coyote. Tree and Forest and the community therein. The infinite richness of our origins, and the concurrent breadth of ways humans form community amongst themselves and what Le Guin called World; World in the sacred sense, outside of time, to which we connect in ritual and from which we, increasingly, have learned to isolate ourselves. Her work is a breaking open of the assumption that technological change and capitalism are infinite corridors of growth and positivity, and has been academically considered in relation to philosophers, economists, and political thinkers as varying as Socrates, Lao Tzu, Marx, and Hanna Arendt. It challenges the long-running paradigm of insularity toward the suffering of people, other living beings, and resources damaged in the pursuit of lopsided, exploitative wealth. She knew that change is the sacred energy informing life; she reminded us that our own economic and political system will change and that we ought to consider and move toward life-respecting sustainable alternatives with all her ferocious commitment to truth.

Through self-revelation, attention to the living roots of language and to the mysterious process of how stories come into the world, she became our Wise Woman, unsparing of well-supported and well-sharpened arrows aimed at stirring us from self-preserving slumber, knowing that community requires full participation.

She was all that, and also very, very funny.

Her influence on my own literary path is beyond measuring. Born in 1952, I was a normal girl, sporting a six-shooter cap gun and coonskin cap, roaming the neighborhood on skates and bike, until I learned to read. Fiction grabbed me and has never let go. I learned that a sunny day meant that I should go outside and play, and formed a strong love for gloomy days, when I could read. In 1959, though I had seen it many times on (black-and-white) television, I read The Wizard of Oz on my family’s journey from Ohio to San Francisco on Route 66, emerging changed at some deep level, primed for a summer of devouring fairy tales while planes taking off from Oahu’s Hickam Air Force Base roared overhead, solidifying a deep lifetime connection to the fantastic within the vast, catholic sea of my readings. Thus, when in 1968 I finished Catch-22 and immediately opened Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, I was hooked for life, though I did not know it then.

I followed Le Guin from fantasy into science fiction without passport, gliding across borders noisily guarded by the armed critics eternally stationed at the interstices of literary cultures. All of her worlds, from coming-of-age to the mythical and the magical, and then the political, offered sustenance. I lived and gained power as a boy in Earthsea, experienced kemmering on the ambisexual planet of Gethen, moved toward adulthood in Orsinia, and studied politics, power, and scientific breakthrough on the twin planets of The Dispossessed. I ran into her in The New Yorker, in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, in Poetry. She was the voice in my heart, no matter what she wrote. She spoke with the voice of a tree, or a coyote, an anarchist, a young boy, an old woman, with equal authority. She wrote nothing I did not devour; nothing that did not enlarge me in some way.

Like most writers, I realized that I was one quite early. By fourteen I spent a good deal of my waking hours writing when I was not reading—not particularly disciplined writing, but torrents of words that might find order as poetry, surrealism, the absurd, or political satire. College and marriage did not change this, but being a Montessori teacher—a practice shot through with joy and humor—did, for a spell, until The Writer Inside intoned dramatically, in a dream on the morning of my thirty-second birthday, “If you want to be a writer, you’d better get started!” And so, I did.

I never imagined that I might someday write science fiction—I was a poet, a surrealist, a humorist, a fantasist, a writer and illustrator of children’s books—or meet Le Guin as a fellow writer.

I did, though, in 1993, when she was Guest of Honor at the International Conference for the Fantastic in the Arts, a year before the publication of Queen City Jazz, my first novel, science fiction, and a New York Times Notable Book. Virginia Kidd, a well-known agent, represented both of us. When Ursula invited me to have a drink with her, we first reminisced about Virginia, and then discussed topics Ursula knew well: writing, career choices, and my own need to remain without boundaries as a writer.

We corresponded sporadically for many years. I knew her as kind, witty, sharp, and funny; helpfully unsparing with well-supported criticism and always ready to share experience, to talk, to be both friend and guide. Thus when she agreed to read This Shared Dream, my seventh novel, and proclaimed it “A tough-minded, kind-hearted, fiercely intelligent novel,” I was and will always remain thrilled at this praise from a woman who embodied all these qualities.

Time is the thing writers prize most, or ought to. We are so cognizant of its passing because we have precise ways to measure it (a story we did not have time to write, or, even, a novel). Ursula was tremendously generous with that increasingly rare resource, granting grace to Sisters of Tomorrow, a scholarly book about the history of women in early science fiction edited by my Georgia Tech colleague Lisa Yaszek and Colin Sharpe and to which I wrote the conclusion. She took time to read it and write “May Sisters of Tomorrow fly long and high,” though she was nearing the end of her time, and of her powers, and knew it.

I know many writers that I admire, respect, and sometimes even love for the brilliance of their thought, but I well know that the writing is not the writer, and that, in person, I sometimes belie the fantasy that readers have created of me based on my writing.

The essence of Ursula Le Guin was that she and her work were one; she shared her own journey. I want to take care to say nothing she would snort at or dispute, were she here to do so, but in my experience that was the case. I delight in reading her correspondence with other writers, her essays, her books about writing, her translation of the Tao Te Ching. I delight in having known her, however peripherally, and rejoice that she has left so much of herself in this world, anchored in the sacred, communal space of the written word, for us to draw on as we head into a turbulent, soul-trying future.

“The Creation of Éa,” the frontispiece of A Wizard of Earthsea, are the first words of Ursula Le Guin’s that I read. Fifty years later—perhaps to the day—they have the same power as when I was, almost, a young woman. Though she sent them forth in time, they came from and connect me to that place where poetry-and hawk-forever fly.

Only in silence the word,

only in dark the light,

only in dying life:

bright the hawk’s flight

on the empty sky.

More on Ursula K. Le Guin

Roz Kaveney at The Times Literary Supplement

Laura Miller at Slate

David Mitchell in The Guardian