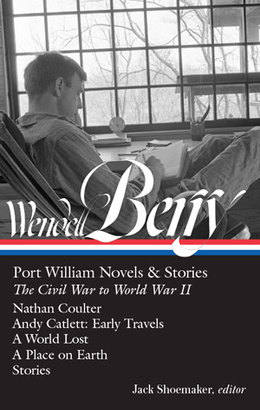

A new author joins the Library of America series this month with the publication of Wendell Berry: Port William Novels & Stories (The Civil War to World War II), a thousand-page compendium of novels and short stories set in the author’s meticulously realized fictional world of Port Royal, Kentucky, set along the western bank of the Kentucky River.

Prepared in consultation with the author, the book includes a newly researched chronology of Berry’s life and career, along with helpful notes; deluxe endpapers feature both a map of Port William and a family tree of some of Berry’s most memorable characters.

Berry responded to Library of America’s questions in writing from his home in Henry County, Kentucky, where he has lived for more than fifty years. We’re particularly pleased to be able to offer the following interview with the renowned poet, essayist, farmer, and activist.

Library of America: This first Library of America volume presents four novels and twenty-three short stories of the Port William sequence in the order of their narrative chronology—a long arc tracing roughly eighty years of rural American life. What might a reader of your work gain from seeing it laid out in this form, instead of in the order in which it was written?

Wendell Berry: “Might” is the right word here. I know this work from the inside, whereas a reader can know it only from the outside. I know it, or have known it, first in the order in which the parts were written. The whole work “from the Civil War to the end of World War II,” as Library of America has published it, was not written from first to last according to a plan. The order of writing was simply the order in which the parts became imaginable to me. A reader, reading from earliest to latest in the order of history, may know this body of work differently, and even better, than I can know it.

LOA: For readers who are familiar with your other work but haven’t read your fiction, how do you see these novels and stories connecting with your nonfiction, or your poetry?

Berry: I have needed all the genres I have used, and, as a sort of common denominator, I have been the same person with the same concerns from one genre to another. As a measure of the usefulness of the genres to one another and to me, I can say that language has become available to me in one genre that was then useful to me in another.

LOA: The early novels Nathan Coulter (1960) and A Place on Earth (1967) appear here in the significantly revised versions you published in 1985 and 1983, respectively. What led you to revisit these books, and how had your ideas about writing fiction evolved in the intervening years? Do you continue to think about revising your work?

Berry: I knew that in the early versions of those novels I had not been as competent a writer as later I had become. In the early versions the writing was sometimes flimsy or thin or misdirected. By the time I realized that the Port William fiction was likely to continue for the rest of my life, I thought I needed a solider, sounder foundation to build on. And so I made the revisions.

LOA: First-time readers may be struck by how prominent humor is in your work—from the overt comedy of “Down in the Valley Where the Green Grass Grows” to a story like “Watch with Me,” where the comic moments are a kind of counterpoint to the grave main situation. Can you talk a little about the role of humor in these novels and stories?

Berry: My people here, so far as I know them, have been talkers and storytellers. Conversation has been, with them, a prominent art. They have remembered the stories of sorrow, which they can’t forget. They have treasured the funny stories because they have needed, and loved, to laugh. The native stories here, as I heard them, were never long, but they were carefully made, shaped for strength, told in the course of both rest and work. My debt to these stories and to our local way of telling them is immeasurable. The comedy is there, I think, less as “counterpoint” than as a necessary completion of the life of the place.

LOA: For the returning veteran Art Rowanberry in “Making It Home,” World War II is nothing less than “the great tearing apart.” If Americans are so often taught to regard World War II as “the good war,” why does it seem to represent such an irrevocable breach, a point of no return, in the Port William novels and stories?

Berry: I don’t think that there is such a thing as a “good war.” But our wars, certainly since our Civil War, have brought industrial innovations, or “progress,” from which there has been no return, upon which there has been no restraint. After World War II, the manufacturers of machines, explosives, and poisons to serve “the war effort” needed a new outlet for their products. That outlet was the industrialization or militarization of agriculture. The idea of maximum power relentlessly applied replaced the standards of husbandry.

As experienced in such places as Port William, this came as an increasing dependence on purchased supplies, and an increasing substitution of technologies for human workers. The ancient dependence on help from nature and neighbors, in fact necessary to the health of the land and its human life, has by now disappeared entirely from public consciousness, and just about entirely from the countryside.

LOA: You’ve written steadfastly about economic landscapes; it’s a theme in both your fiction and nonfiction. But it seems as if the current dwindling farm population is echoed in the scarcity of contemporary fiction set in rural America. Is there a connection between these two things?

Berry: Most writers, like most people, have now acquired urban consciousness and urban attitudes which too easily imply disregard or contempt for “country” things, including the natural world, in which and from which we live, and the economies of land use. And so the “lobby” for good husbandry of the working landscapes of farming and forestry is now drastically underpopulated and ignored.