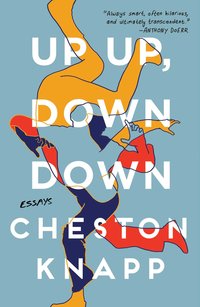

Our latest guest post by a contemporary writer comes to us from Cheston Knapp, whose debut essay collection, Up Up, Down Down, is out this week from Scribner.

In the book’s seven interlinked pieces, Knapp works outward from all-American phenomena like fraternities, UFOs, and skateboarding to explore larger concerns like the nature of faith, community, and what constitutes maturity in the early twenty-first century.

Up Up, Down Down has already won the praise of prominent names in creative nonfiction: Leslie Jamison writes that “its insights will keep echoing in me for a long time,” while Maggie Nelson cites Knapp’s “uncanny, welcome ability to make so-called mainstream or dominant culture . . . appear newly strange, and newly open to analysis.”

Below, Knapp discusses the writers and artists who have influenced his writing.

Ralph Waldo Emerson. Here be the wellspring, the mighty fountain from which all other American essayists surge or trickle forth. Hardly a month goes by that I don’t find myself drawn, almost gravitationally, as though part of some lunar cycle of my soul, back to his work. It’s one of the major dangers of canonization, that familiarity with a writer’s name can dim the strangeness of his or her work, and this had happened to Emerson for me, until about ten years ago, when I started to read him again and rediscovered exactly how weird his essays are. There’s something feral about them, which I think has to do with the untamable way his mind moves and, furthermore, the way he lets us observe it moving. He allows himself to occupy that ideal middle distance between ignorance and certainty, grants himself the freedom to speculate, to mull, to converse with himself, and so us, on the page. It took me a goodly long time to understand how generous this is, and how essentially humane.

William James. Between the brothers James, I’d take William any day of the week. (“Henry James most likely died a virgin.” Or so hazards David Markson in Reader’s Block…) My sense is that folks unjustly assign to William’s work the rank, cheesy fetor of scholarship, an academic taint funk. But his best writing—e.g. in the “Sick Soul” chapters of The Varieties of Religious Experience and “Is Life Worth Living?”—is animated by lived experience, by an ambition to shrink the distance between ideas and life. He shows us how one’s life can be both a breeding and proving ground for one’s ideas, and he gives his curiosity free rein, pursuing all species of quarry on the page. There’s this bit I really like from The Man Without Qualities, where Musil writes, “A man who wants the truth becomes a scholar; a man who wants to give free play to his subjectivity may become a writer; but what should a man do who wants something in between?” For an answer you could do a lot worse than saying, “Follow the lead of William James.”

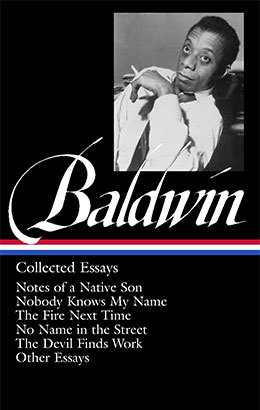

James Baldwin. Perfection is a dicey and divisive notion, particularly when it comes to art. But if I were forced at knifepoint to name the perfect American essay, I wouldn’t hesitate to say, right after I’d finished whizzing myself, “Notes of a Native Son.” I was trying to think of a visual analog for what Baldwin pulls off in the essay, something that captures the way he balances the personal and the public material and negotiates the tonal Bermuda Triangle of anger, resentment, and grief, and the best I could come up with was this performance I once saw at halftime of a Blazers game: a woman wearing a jazzy leotard summited an eight-foot unicycle, balanced a cereal bowl on her head, and then flipped other cereal bowls from her foot up into the one on her head. This continued for a while. But the act culminated in her stacking four bowls on her foot, balancing them on her shin, and flipping them all up into the growing collection on her head. It was among the most spectacular things I’ve ever seen, just as the essay continues to be one of the most spectacular things I’ve ever read.

William Gass. It can still loosen my noodle, the fact that I’ve been alive on earth, in America, at the same time as certain writers. Saul Bellow. James Baldwin. Ursula Le Guin. John Ashbery. Joy Williams. And God, William Gass. (When Gass was my age, my mom was two. (Time!)) Over and over he demonstrates how, when writing about ideas, rigor need not be followed by mortis. That one can expect the same aesthetic delights from an essay as a story or poem. Language is genre-blind, after all—words don’t know who or what they’re working for. And as he himself says, encouragingly (?), “It’s our words, roughly, we remember; oblivion claims the rest.” Plus, it turns out he also moonlighted as self-help writer: “There isn’t very much satisfaction in getting the world to accept and praise you for things that the world is prepared to praise. The world is prepared to praise only shit.”

Randy Newman. Don’t ask.

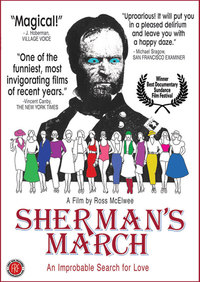

Ross McElwee. To watch McElwee’s movies is to study with a master of digression. I’m even tempted to say that his movies formalize the digression, that in his hands they’re not just flappy skin tags on the body of a piece, but are the body itself. He pursues them, relentlessly, until the viewer can no longer consider them a digression. I think this is why they’re not only about life, but also manage to actually feel so much like it. Sherman’s March, especially, continues to astound me, and I’ve probably seen it over ten times at this point. It’s tender, funny, smart, honest, generous, ambitious—a masterpiece, by which I mean that it makes me want to try to be all those things at once, too.

The managing editor of Tin House, Cheston Knapp lives in Portland, Oregon, with his wife and son. Knapp is also a photographer who had his debut solo exhibition, Reclamation, in Portland in 2017.