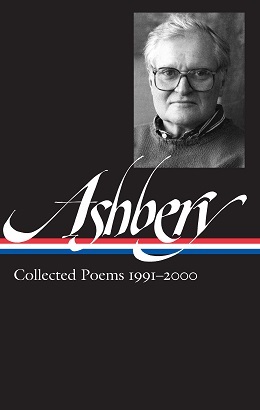

The second volume of Library of America’s John Ashbery edition, Collected Poems 1991–2000, arrived earlier this fall, just after the poet’s death on September 3 at the age of ninety.

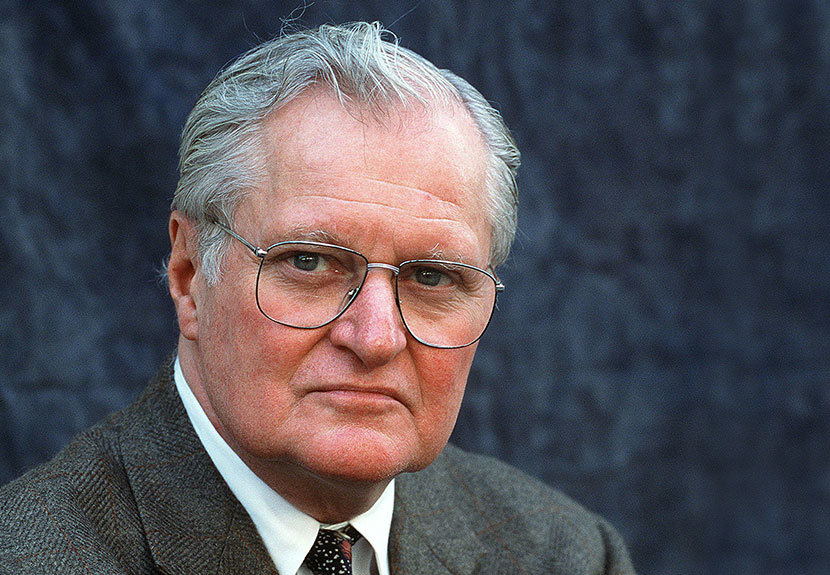

Mark Ford, editor of the Ashbery edition, is one of several poets and critics who contributed to LOA’s online tribute page for Ashbery, and he also provided The Guardian with an obituary in which he summed up:

Ashbery’s work presents a restless, supremely sophisticated imagination meditating self-reflexively on experience, creating in the process a “flow chart,” to borrow the title of his longest work, of the vagaries of memory and the fluctuations of consciousness.

Below, Ford describes some of the revelations he encountered while editing the book, and explains what makes this phase of Ashbery’s long career so distinctive.

Library of America: With Ashbery’s death in September, Collected Poems 1991–2000 has an unintended valedictory quality. How does this decade fit into the overall arc of his career, now that we can see it whole?

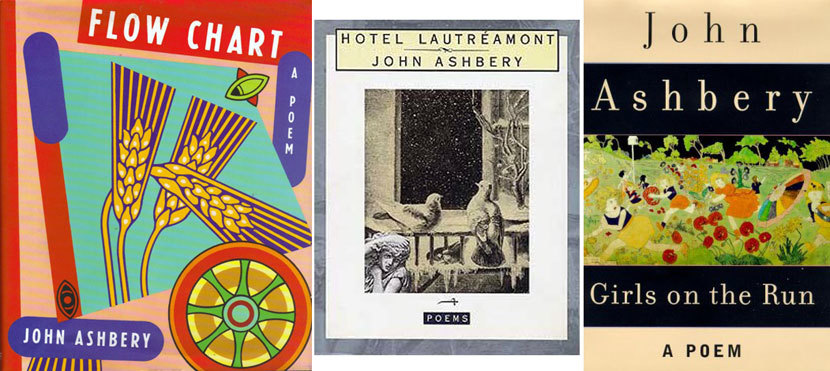

Mark Ford: I think the ’90s might be characterized as Ashbery’s most expansive decade. There is a plenitude to the poems of this period, most obviously signaled by the enormously long Flow Chart, that suggests he was eager to braid together all the different poetic idioms that he had evolved in the earlier phases of his career. This can make these poems occasionally sound as if they are bouncing echoes off his own previous work. He also, I think, pushes further the notion of the lyric as not only presenting an artfully crafted transcription of the fluctuations of consciousness, but as an echo chamber in which literary allusions to favorite poems, such as Cowper’s “The Castaway” or Thomas Lovell Beddoes “Dream-Pedlary,” as well as references to all manner of films and comic strips and operas and waltzes and symphonies, collide with personal memories or random speculations, speculations both profound and goofy—but “collide” is perhaps too strong a word, for in this period the various sources tend to slide seamlessly into each other.

LOA: More than two and a half decades after publication, 1991’s Flow Chart stands alongside Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975) as one of Ashbery’s major achievements. What makes Flow Chart significant?

Ford: In 1985 John was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, which enabled him to give up teaching and art reviewing, and devoted himself wholly to poetry. Two years later his mother died, and the painter Trevor Winkfield, to whom Flow Chart is dedicated and who furnished the painting on its original cover, suggested he write a really long poem not so much about his mother, as about the thoughts and memories triggered by his feelings for her.

Flow Chart is not only very long itself, but makes use, mainly, of long lines, as did, incidentally, his first major long poem, “The Skater” of 1965. Flow Chart’s length was actually determined in advance—John set out to keep writing until he’d filled 100 typewritten pages. In the event one of these pages went astray in the publication process, but it turned up in the Ashbery archive in Harvard, and has been restored in this new edition.

What makes the poem significant? Well, in my opinion he was working at the height of his powers in the late 1980s, and Flow Chart, for all its serpentine divagations and weird experiments—his use of a double sestina for instance, with endwords derived from a double sestina by Swinburne—channels strong emotional currents.

LOA: In 2005, you wrote that Ashbery “rather stubbornly still cherishes the old Whitmanian ideal of aiming the poem at as wide a constituency as possible, however marginal the poet’s current status within society itself.” How does that aspiration inform the poems in this new collection?

Ford: There can be a tendency among critics to classify American poets as belonging to particular tribes or factions, but I think John always nurtured the ideal of a poetry, like that of Whitman, capable of containing multitudes, of speaking for all. Indeterminacy, often through pronoun confusion (“It wants to go to bed with us,” Kenneth Koch once quipped, might be taken as the archetypal Ashbery line) is the principal means whereby he achieves this concept of the poem as “one-size-fits-all,” as he once put it, as appealing to readers on the most general terms, rather than in relation to directly signified affiliations.

His ’90s poems find a variety of new ways of conjugating the mish-mash of voices that surround us—“A Driftwood Altar,” the title of one of my favorite poems in Hotel Lautréamont, perfectly catches the sense these poems often create of improvising an existence out of whatever happens to surround us, moment by moment.

LOA: Girls on the Run (1999) is a book-length poem loosely based on the work of the outsider artist Henry Darger. Was there any precedent in Ashbery’s work for his being inspired to such an extent by one artist? What do you think he responded to in Darger’s somewhat outré imaginative universe?

Ford: Well, obviously Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror is based on a work by Parmigianino, but it also relates various other incidents from Vasari’s life of the Italian painter. _Girls on the Run is much less directly an ekphrastic poem, to use the technical term, than Self-Portrait, developing a kind of shadow-narrative rather than asking us as readers to relate particular sections to particular Darger pictures.

|

| Collected Poems 1956–1987 (LOA’s first Ashbery volume) |

I think the poem mines his fascination with childhood—first articulated in the very early “Picture of Little J. A. in a Prospect of Flowers”—as well as with children who feel at an oblique or estranging angle both to adults and to other, less troubled children. As Karin Roffman demonstrates in her account of John’s childhood and adolescence in The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life (published last year), it wasn’t easy for him growing up gay on a remote farm in northern New York State; and the death, when he was twelve, of his younger brother from leukemia made his adolescence even more difficult. In Girls on the Run he both explores a fantasy of childhood innocence, and at the same time reveals how even that fantasy is menaced by impossible difficulties and dangers. In this it matches Darger’s world, which can at first look cute and wholesome and fun, but soon turns out to be dark and weird and disturbing.

LOA: Along with seven books Ashbery published between 1991 and 2000, the new volume reprints twenty-five poems that have never been collected in book form before. Are there standouts for you in this gathering? What do they add to the collection?

Ford: My favorite is “These Symptoms I Know So Well,” which was originally published in Verse in 2000: “Aching, we lay aside / the book of summer, winter’s ruts are still ahead.” It reveals Ashbery in fascinating dialogue with romantic poems such as Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (“The loon fixes / us with its stare then”) and Keats’s “Eve of St. Agnes” (“Lock up your casement, lovers, / for night, noble night, the bearer of shadows, is coming”). I think it was Ashbery’s ability to write modern poems that also reached into the traditions of romanticism that first excited me, and “These Symptoms I Know So Well” is a good example of this.

They are pretty well all interesting in various ways, and collecting them here will save future Ashbery scholars from hunting through databases, as well as prompt speculation as to why they were passed over when he was assembling individual volumes.

LOA: Given your familiarity with Ashbery’s poetry, were there any discoveries or surprises while you were preparing this volume?

Ford: Assembling the notes, I was struck by the range of his references, and their recondite nature. You don’t, when reading an Ashbery poem, need to “get” his allusions in the way you do with, say, T. S. Eliot or Ezra Pound, and indeed sometimes you don’t even spot that an allusion is being made. But anyone interested in Ashbery’s tastes in film or music or poetry or fiction could do worse than to flick through the notes at the back of the book. My hope, or rather my experience, is that this can lead to great discoveries—that is, if you like Ashbery’s poetry, you might be intrigued, to take the most obvious example, by the reference to Lautréamont in the title of Hotel Lautréamont and seek out Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror. And then enjoy it, if that’s the right word. . .

To put it another way, the discoveries and surprises came when I used the poems’ references as tips for further reading or listening or movie-watching, and I derived a further pleasure from pondering what it was about the work in question that appealed to him. Sometimes we’d discuss these matters in our email exchanges—a selection, incidentally, of those parts of his letters to me in which he riffs on movies and books and music is to be published in a John Ashbery tribute number of the British poetry magazine PN Review early in 2018, and I strongly recommend it!