Just out from Metropolitan Books, Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder is a biography of the Little House on the Prairie author by Caroline Fraser, who edited Library of America’s two-volume Wilder edition in 2012.

Prairie Fires situates Wilder’s life in a broad historical context stretching from the white settlement of the upper Midwest in the mid-1800s to the dawn of the modern libertarian movement in reaction to President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Fraser’s approach has already won praise in the New York Times Book Review from noted Western historian Patricia Nelson Limerick, who singles out “the extraordinary care and energy Fraser brings to uncovering the details of a life that has been expertly veiled by myth.” Reviewing Prairie Fires for The New Republic, Vivian Gornick calls it “an impressive piece of social history that uses the events of Wilder’s life to track, socially and politically, the development of the American continent and its people.”

Last week we published an excerpt from Prairie Fires as a News & Views feature; today we’re pleased to present an interview with Caroline Fraser. In addition to editing the Little House novels for Library of America, Fraser is the author of Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution (2009) and God’s Perfect Child: Living and Dying in the Christian Science Church (2000). A resident of New Mexico, she has written for The Atlantic, the Los Angeles Times, and The New York Review of Books.

Library of America: Prairie Fires opens with the Homestead Act of 1862, which encouraged migration to the Western U.S., and its gruesome sequel, the U.S.–Dakota War. Why did you choose to begin your book with these events that took place several years before Wilder’s birth?

Caroline Fraser: When I was writing the notes for the Library of America edition of Wilder’s work, the “Minnesota massacre” (as Wilder called it) stopped me in my tracks. It was an astonishing and horrifying event in American history that I’d never heard of, and it was one of things that made me want to write a historical biography.

Together, the Homestead Act and the war established the conditions for the final agricultural settlement of the Great Plains. The two events are not often yoked together, but I saw them as essential to understanding the frontier that Laura Ingalls was born into. At the beginning, the war took the form of a sudden and unprecedented attack on white settlers, triggered by widespread starvation among the Dakota and treaty violations that were extreme even by standards of the day. Prior to 1862, there were relatively few casualties caused by Indians on the overland trails, so it came as a complete surprise: During the first days, some 600 white settlers, men, women, and children, were killed in an attack of great ferocity.

Tragically, all Indians in the region would ultimately pay the price for that attack: In the aftermath, white officials and politicians took the war as a pretext for extermination and embarked on a plan to rid the entire state of Minnesota of virtually all native people, not just those who had taken part in hostilities. That extreme reaction created a population vacuum in the southern half of the state which would in short order be filled by farmers like Charles Ingalls.

Understanding the U.S.–Dakota War is vital to understanding Wilder’s most famous novel. In her memoir, Wilder recalled seeing the ruins of burned-out houses near the town of New Ulm, much of which was burned to the ground during the war. The “massacre” is mentioned but never explained in Little House on the Prairie. The notorious slur that arose during the aftermath—“the only good Indian is a dead Indian”—comes up several times in that book, introducing “Laura’s” ambiguous response to Indians, her fear tempered by fascination and identification.

LOA: How reliable are the Little House books themselves as sources for Wilder’s biography? To what extent does she take liberties with her own history in the books?

Fraser: Wilder always spoke of the books as a memorial to her parents, and she felt strongly that they were true to her experience. I’m sure they were, emotionally. So the books were “true,” but they were not accurate in every detail, as she herself acknowledged on occasion.

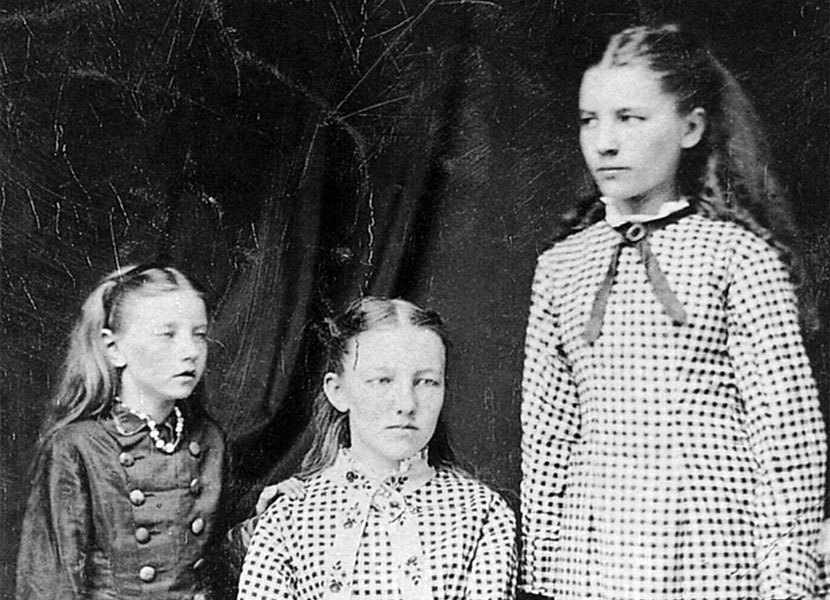

In consultation with her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, Wilder changed the chronology of her life and burnished the portrayal of her parents by leaving out material that did not reflect well on her father as a provider. She skipped an entire year in Burr Oak, Iowa, which the family fled in the middle of the night to avoid paying debts, and a particularly aimless period in Walnut Grove, when the family had no land of their own. There Laura began working as a servant for the Masters family, but you never see this in her books.

She added fictional scenes and invented characters, such as “Mr. Edwards,” keeping the dog Jack with the family until By the Shores of Silver Lake. Jack would become a real favorite among readers, part of the novels’ emotional apparatus adding to the sense of a secure, stable family life. But in real life, the dog was left behind when the Ingallses left Kansas. The family may well have been every bit as warm and loving as they appear, but they were never as secure as the Little House books suggested.

LOA: The Library of America edition of the Little House books includes The First Four Years, which wasn’t published until 1971, fourteen years after Wilder’s death. As your new book mentions, the markedly more adult, even harsh perspective of The First Four Years makes it an anomaly in the series. Did you have any reservations about including it in the LOA edition?

Fraser: The manuscript of what Wilder called “The First Three Years” is an essential text in understanding both her life and her writing process, I think. It helps in evaluating the gloss she and her daughter put on the raw material of her life. Through it we hear her unvarnished voice. That certainly comes through in the eight original books as well but is often modulated with a gentler tone and cheerier outlook.

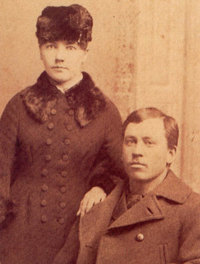

The adult perspective of that final manuscript seems entirely appropriate given that Wilder married at eighteen and then had to negotiate some of the worst experiences of her life—crop failures, debts, her husband’s illness and disability, the loss of child, and their home destroyed in a fire. It’s a vivid, stark account that reveals a great deal about her actual feelings—her love for her husband, her insecurities about her new adult responsibilities and her difficulties in raising a child while coping with all her duties on the farm. The pain of their losses really comes through, and when you consider that she wrote it decades after the fact, it’s quite a remarkable document.

In the Library of America edition we used the published text from 1971, but provided notes explaining the more substantive editing changes that were made, including the graphic language Wilder used in describing childbirth (deemed unsuitable for children) and a sentence in which she expressed doubt about her husband: “How much could she depend on Manly’s judgment, she wondered.” Apparently, in 1971, the idea of Laura distrusting Almanzo was a bridge too far.

LOA: Any biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder necessarily has to reckon with her daughter, the gifted, complicated Rose Wilder Lane. What’s your assessment, finally, of the nature of their collaboration on the Little House books?

Fraser: Lane was clearly a powerful force behind her mother becoming a writer in the first place. Early on, during her period writing for the San Francisco Bulletin, Lane provided a model of the writing career (albeit quite a sensational one) and pressed her mother to take up the trade by writing for farm newspapers. Later, she secured for Wilder a feature magazine assignment at McCall’s.

In other crucial steps, Lane would help Wilder find a publisher for Little House in the Big Woods, providing plenty of advice on how to structure the story and arranging for her own agent, the very competent George Bye, to handle her mother’s work as well.

Their editorial collaboration appears to have been fairly involved, with Wilder writing her books longhand, producing draft after draft of each manuscript. Then Lane would take her turn, typing out revised versions, often adding dialogue, punching up scenes, and—especially early on—providing more structure. She deserves great credit for her major role in making the books what they are.

But the teamwork was no more involved, I think, than many other close editorial relationships—when you look at the famous Maxwell Perkins, for example, editor and friend of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, he too was intimately engaged in the process of creation and revision, even suggesting the idea and structure for Rawlings’ The Yearling.

So, given Wilder’s extensive work on drafts and her strong views and detailed instructions on later revisions, I don’t think their process meets the definition of ghostwriting. Indeed, Lane wrote her own adult versions of her mother’s material in two serialized novels, Let the Hurricane Roar and Free Land, and they exhibit a very different sensibility. As I suggest in my biography, the mother and daughter working together were able to produce something that neither of them might have accomplished on their own.

LOA: Readers encountering Rose’s life story for the first time may be startled to find how many present-day political controversies it touches on. Was that a surprise for you as well?

Fraser: I had some notion of this from writing the notes for the Library of America editions, but yes, I was surprised at the extent of it, particularly at how today’s divisive political rhetoric so closely reflects that of the 1930s. To read Lane’s letters excoriating FDR and the “New Dealers” and Wilder’s denunciations of Truman and Eleanor Roosevelt is to be strongly reminded of the conservative right-wing blogosphere of today. Lane takes up many of the same concerns: rejection of big government and federal agencies, an abhorrence of taxes, and the championing of absolute self-reliance.

One of the reasons I wanted to follow up the Library of America edition with a historical biography was to examine Wilder’s connection to the ecological transformation of the Great Plains. Even as she took part in it, she mourned the coming of towns and railroads and the loss of wildlife and open space. In the run-up to the Dakota Boom, which sent farmers like Charles Ingalls out to Dakota Territory, there was a battle between the federal government and its own scientists, who warned against letting loose thousands of homesteaders in a region too arid to support them. The Boom won out, but it presents unmistakable parallels to today’s political posturing over climate change.

Wilder herself experienced the disastrous results of the inflated expectations for Dakota farming, fleeing the region during the drought of the 1890s as part of an extraordinary mass exodus. She saw the same pattern repeated during the Dirty Thirties with the Dust Bowl, and mourned the collapse of the land all over again. Yet despite her work for the Federal Farm Loan program, she continued to feel that farmers must be solely responsible for their own survival.

LOA: On the face of them, the Little House books seem like unlikely children’s classics, dwelling as they do on work, discipline, and even privation amid the harsh realities of life on the frontier. How do you explain their enduring appeal for younger readers?

Fraser: The Little House books are at once intensely comforting in their portrayal of a warm, loving, secure family and thrilling and alarming, in their depiction of terrifying events—the locust plague of the 1870s, the blizzards, the prairie fires, the beautiful yet fearsome wolves, the constant approach of hunger and potential ruin. Yet it’s only as an adult that I noticed the darker strains. For children, I think, the true pleasures lie in the adventures, the growth of Laura into a young woman, and the intensely satisfying happy ending toward which the books progress.

But those darker tones are there. Wilder herself wrote movingly about her parents’ protective instincts, suggesting that they defended their children against fear. Describing the deaths and injuries that commonly took place on the frontier, she once wrote, “Sister Mary and I knew of these things but someway were shielded from the full terror of them.” Were they? I think that remains one of the deep and unresolved tensions in these works, something that keep us coming back to them, over and over again.