The tenth and final volume in Library of America’s Philip Roth edition, Why Write? Collected Nonfiction 1960–2013, gathers more than five decades of writing on a wide range of topics: his own fiction and that of forebears and contemporaries like Kafka, Bellow, and Malamud; his deep engagement with fellow writers in Cold War–era Eastern Europe; and the state of American culture across several tumultuous decades.

Drawn from the full span of Roth’s remarkable career, the thirty-seven essays, addresses, and interviews in Why Write? offer glimpses of a writer, as he notes in the book’s preface, “out from behind the disguises and inventions and artifices of the novel.”

Via email, Roth shared a few thoughts on the collection with Library of America.

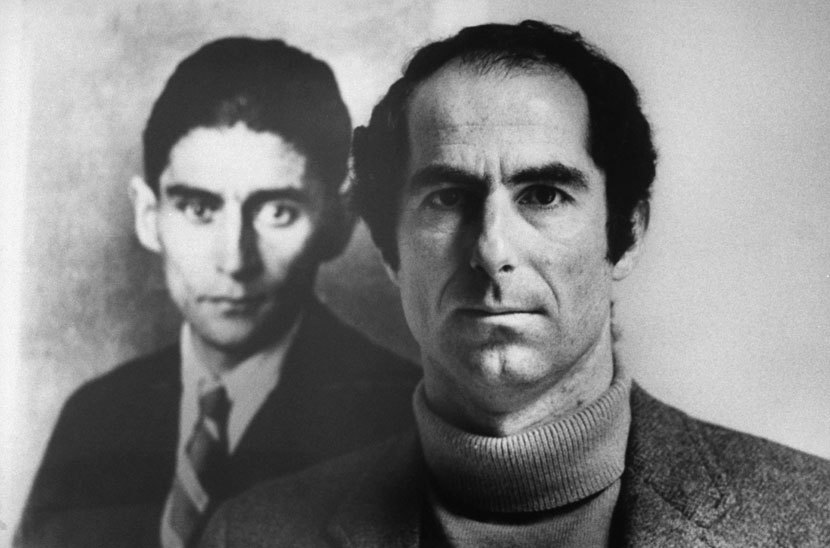

LOA: “‘I Always Wanted You to Admire My Fasting’; or, Looking at Kafka,” the piece you’ve chosen to open Why Write?, is a fascinating hybrid: an essay on Kafka that morphs into a speculative and very funny tale imagining him living out his later years in New Jersey. It’s your first foray into the sort of alternative history you went on to explore in The Ghost Writer and The Plot Against America. Do you recall the inspiration for the Kafka piece, and what led you to veer from essay to imaginative fiction?

Roth: For many years during the ’60s and the ’70s, I was teaching comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania. Sometime in the early ’70s, I began teaching Kafka’s work, the novels, the short stories, and a sampling of the letters, including the famously harrowing long letter to his father. My piece, “I Always Wanted You to Admire My Fasting,” began as a biographical essay about Kafka’s love affair at the end of his life with nineteen-year-old Dora Dymant and about the connections this touching affair—probably his most fulfilling engagement ever with any woman—might have had with his writing.

As best I can remember, it was writing about the tender pathos of those years that spontaneously and quite suddenly produced the image of Kafka as he might have been had he—like his hero Karl Rossman in his lesser-known novel, Amerika—taken refuge from Europe in the United States. As a Hebrew school student in Newark during the war years, I had known of two such refugees who did their best, against all odds and in the face of every American distraction, to make us conversant with our ancient tongue, and I thought, “What if one of them had been Franz Kafka?” Thus the metamorphosis from biographical essay into biographical fantasy.

LOA: From the 1970s onward you engaged deeply with writers from “the other Europe,” particularly Czechoslovakia. Shop Talk features your discussions with Ivan Klíma and Milan Kundera. What drew you to Eastern European writers, and what did you learn from them?

Roth: What drew me first to the writers of Eastern Europe during the Cold War years was their ruinous entrapment both as writers and citizens in totalitarian Communist regimes propped up by the old Soviet Union. I was nothing more than a tourist in Prague in 1972 when I was first introduced to the plight of these writers. My Czech education, as I explain in Why Write?, began then and broadened for the next seventeen years, until finally Communism was overthrown in Eastern Europe in 1989. Courage and anguish—that’s what I saw manifested in the many men and women artists that I met in those years during my regular visits to Prague. Hardship and defiance. Punishment and fortitude. Family suffering and family cohesiveness. Burning rage and superhuman composure. What did I learn? The magnitude of the hatred that can be inspired by writing—the sheer barbarism it can energize.

LOA: Many pieces in Why Write? are interviews, dialogues with literary figures ranging from Joyce Carol Oates and Edna O’Brien to Aharon Appelfeld and Primo Levi. Are there exchanges you remember as particularly revealing or unexpected?

Roth: You don’t mention my conversation with Isaac Bashevis Singer about Bruno Schulz. Of all the writers that appear in conversation with me in Why Write?, Mr. Singer is the only one I had not already known. Consequently, our little discussion at his apartment that day had, for me at least, the charm of discovery, the encounter with a vivid type of Jewish personality at once winningly clever and bewitchingly sly. He couldn’t have been more hospitable or mischievous.

Talking to writers who were already friends, like Aharon Appelfeld, Ivan Klima, Edna O’Brien, and Milan Kundera, had its own kind of strangeness, at least at the outset, because of the unaccustomed formality of an occasion that is governed by certain protocols. As for Primo Levi, we had met briefly once before, but by the end of the four days we had spent together—traversing Turin on foot with him as my guide, dining at night with Lucia, Primo’s wife, as well as some of Primo’s close friends, and endlessly talking during the mornings and afternoons—I had thought to myself, “I have made a wonderful new friend!”, and then seven months later he was dead.

|

| Novels & Stories 1959–1962 (LOA’s first Roth volume) |

LOA: Your very last word in Why Write? about Portnoy’s Complaint is “Alexander Portnoy, R.I.P.” Have fifty-some years of sexual liberation changed how you read the book? Can you imagine imagining Portnoy in 2017?

Roth: Well, in 2001, forty-two years after the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint, I imagined a novel entitled The Dying Animal, which demonstrates just what fifty years of sexual liberation can do to a man. The novel’s protagonist, David Kepesh, is the erotically liberated creature Alexander Portnoy dreamed of being but was too conscience-ridden and biographically compromised ever to become. David Kepesh is Portnoy unPortnoyed, the compleat libertine, actualized miraculously by way of the Sixties’ revolutionary fervor, which is what he explicitly credits for freeing him of all the old impediments to ecstasy. The Sixties do for Kepesh what Dr. Spielvogel could never begin to do for poor Portnoy, if even he, as a Freudian analyst, should want to expedite such an anti-social transformation. Kepesh’s therapy is history.

LOA: Re-reading these career-spanning pieces to prepare the final texts for this volume, what surprised you?

Roth: I was most surprised finding so many pieces responding, in one form or another, to the charges of anti-Semitism that had been leveled against me at the outset of my career. I had to wonder, while rereading them, “Why did I have to so strenuously defend myself? Why didn’t I just ignore them and get on with the job?” Why didn’t I?

I was in my twenties, for one thing, with no experience whatsoever of an assault so consequential—and so public—on my character. Also, I was being charged with embodying and propagating a hatred—Jew hatred—that I myself despised. I was angry and I was wounded, and so I lashed out with as much equanimity as I could muster. Now, in my eighties, of course I think, while reading these pieces, “Why did you bother?” The answer is because when it all happened, I wasn’t in my eighties. I was nearly as far from one’s eighties as a writer can get.