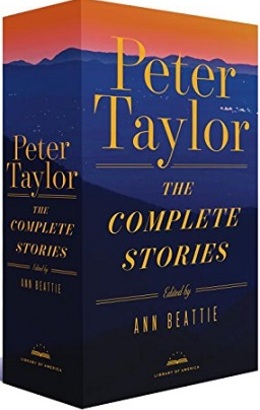

Published this month by Library of America, Peter Taylor: The Complete Stories is a two-volume set gathering the short fiction of the writer Madison Smart Bell called “arguably the best American short story writer of all time” in 1986. Presented in the order of their composition, the fifty-nine stories span more than half a century and explore, in exquisite detail, the private and public dramas of a Tennessee gentry living through an era of unprecedented social change.

Library of America is especially fortunate to have as the editor of Complete Stories Ann Beattie, who not only knew Taylor as a colleague and friend but is also a distinguished fiction writer herself, the author of ten short story collections and eight novels. A recipient of the PEN/Malamud Award in 2001 and the Rea Award for the Short Story in 2005, she is Edgar Allan Poe Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Virginia. In the following interview with Library of America, Beattie shares a fellow practitioner’s insight into what makes Taylor’s art unique.

LOA: As you acknowledge in your introduction to The Complete Stories, Peter Taylor remains something of a mystery man in contemporary American fiction. How would you characterize his contribution to American writing, and what do you hope this two-volume Library of America edition of his stories will achieve?

Beattie: The mystery is only why he isn’t better known. Circumstance had something to do with that. Other writers of his group got such appreciative attention, so soon, that he was elbowed aside. The counter argument to that, of course, could be that there’s room to single out many writers and to praise them all if they deserve it—but that strikes me as much too easy. Sometimes an exceptional writer comes along at the right time and manages to find solid footing (a particular publication that embraces the writer and promotes the work; the right agent; a book that speaks to the moment, even when—maybe especially when—it’s not premeditated); other times, writers don’t hit it right immediately, but they garner attention (a reviewer; a particular editor) and they’re carefully watched—or it can be as simple as this: their mentors call attention to them. Peter emerged under the tutelage of Allen Tate (whom Peter greatly admired), Robert Penn Warren, and the group that came to be known as the Fugitive Poets. Certainly, back then, a lot of attention was directed toward Tate and John Crowe Ransom, among older, more established writers, but I don’t think (this is not a value judgment) their reputations have endured into the present day, so there’s been little interest in looking, retrospectively, at what writers might have been neglected. Perhaps these men (they were primarily male, though Jean Stafford was among them, as was the brilliant Elizabeth Hardwick) were a bit more hermetically sealed than they knew (or wished to be). It’s not usual now, but when the numbers were lower (before the proliferation of MFA programs), writers often learned through one-on-one apprenticeship.

Looking back, Peter and his group were small in number, and in remaining close (though they certainly also criticized each other’s writing, those times they weren’t being rather fierce with one another personally) they might have contributed to marginalizing themselves. Does it help to be thought of as a writer who’s part of a movement or group? Not necessarily. The attributes and inevitable limitations of the group (at least, as critically perceived) can also work against an individual writer. Peter Taylor is on record as being skeptical of literary awards and prizes, but of course he was pleased when they were conferred. The Pulitzer came rather late in his career. His mentors and many of his writer friends were gone. It wasn’t a time when he could follow through and jump into the limelight to receive a larger readership. He had health problems. And he was disinclined, anyway. I have to admit that: he was disinclined.

As to why many reviewers overlooked him? In paraphrase, his writing is difficult to make sound exciting (a real compliment, that). In terms of his often baroque structures and the stories’ underpinnings, he was so clever that he accommodated people who read on the surface, while he revealed to more sophisticated readers what he was really up to. Other writers (such as Eudora Welty) were bringing new attention to the short story at the same time Peter was revitalizing the genre, but as time went on, and as Peter became even more of a magician, he ended up standing there all by himself. Therefore, you could look away if so inclined.

LOA: Readers discovering a white Southern writer in 2017 will perhaps inevitably be curious about how race figures in his work. Taylor’s career spanned the entire Civil Rights era; how is that time reflected in these stories?

Beattie: Race figures in Peter’s work in ways that resemble the way it did in his historical moment; it was ubiquitous, influential, but often not addressed directly. We have become far more self-consciously vocal about injustices that have festered through our entire history, so that today there’s pressure on artists to foreground these issues. True, writers such as James Baldwin used literature to express outrage and press for change, but any number of threads co-exist in the culture at any given time. Other pressures and goals were there; in visual art, critics such as Clement Greenberg almost militantly demanded that the arts explore their own means, emphasizing form rather than content, and the joys of art for art’s sake would not have been foreign to Charlie Parker or John Barth.

Peter Taylor was, like all of us, a product of his time as well as an individual with his own project. In 1983, an interviewer named Robert Daniel asserted that Peter’s fiction “was not concerned at all with political or social issues, is it?” “No,” began the reply—but I think Peter was making a pre-emptive strike against the question he sensed was coming. His answer: “No, but when I’m writing I discover sometimes what I really think about social issues. . . I’ll discover what I think of a lot of the issues that people talk about constantly.” Writing as self-discovery is so usual, it’s pretty much synonymous with the endeavor of writing. Part of why people write is to make sense of their personal wonder at the weirdness (including the injustices) of the world, and it never stops supplying them with material. Navigating through life is hazardous, and there are any number of shoals, some seen, some just far enough under the surface to haunt our dreams.

LOA: Discussing his early work in a 1987 Paris Review interview, Taylor said that “I found the blacks being exploited by the white women, and the white women being exploited by the white men. In my stories that always came through to me.” Comment?

Beattie: He was fascinated by, and disturbed by, power, and power imbalances.

His stories are full of people dependent on one another. These needs cut across class, they cut across age, sometimes they directly involve race (“Bad Dreams” or “A Friend and Protector”), but in no case does the writer back away from all that’s implied in these complex relationships in which people are burdened with their sometimes differing, sometimes overlapping needs; those matters seem to become the dynamic of the stories, but that’s way too simple. The stories are complex psychological studies of individuals. The tension that informs the reader of some underlying mystery resides below the surface, rather than in the moments dramatized. Being dependent, of course, is an inherent imbalance of power. I find the ending of “The Old Forest” magnificent in articulating the story’s subtext: not because we applaud Caroline by today’s standards (nor would that have been a good idea back then), but because the writer is explicit about what we must understand—the unspoken ways in which men and women respond differently to a conundrum. Through the narrator’s perspective (which is only his), we reach an epiphany when he does. But he’s had time to think. We’re just finishing the story for the first time; we’re getting to know it. The phrasing is elegant; the last paragraph is like watching someone skate a perfect figure 8. That exuberance, that energy, carries the story somewhere else, beyond its particulars. It’s great, but on some level it’s also a performance. I’m not saying the reader should be skeptical of the information delivered, but rather that the cloth being woven was never as recognizable as we’d come to assume. The cloth shows a variation, an irregularity in its weave, in the last paragraph. The word “pride” was cagily, deliberately chosen, conjuring up (even if only subconsciously) a pride of lions. This returns the reader to the Old Forest, to the different associations it carries for men and for women. Everyone in the story takes—we all take —what we need. (Yes; I’m still reacting to Peter’s Paris Review statement, while recontextualizing it a bit.)

One last thought: The reader would be missing what’s going on in “A Friend and Protector” to read it as a story about race and class. That’s obvious, but what’s unstated is larger than the incidents. Again, as in “The Old Forest,” a woman is gradually revealed to have great power, but my reading of the story finds this to be almost unbearably sad: the husband and wife employ Jesse to look after their needs (they are white, wealthy enough to have a servant)—but by story’s end, they primarily fail themselves. Jesse (with his drinking and his wild actions off the page) has always been the opposite side of their coin. In Freudian terms, the Id to their Superego. He ends badly—he does not triumph—but ironically, he fits in elsewhere, even though that means residing in the asylum (“they will almost certainly never let him go.”). At story’s end, Taylor portrays Jesse’s employers—the ones who do have a kind of power—as devastated, as if they’ve been deservedly struck by lightning (metaphorically speaking). The religious symbolism, the wife’s simultaneously animalistic and penitential position (she actually topples, after falling on her knees!) shows us, visually, how their story, itself, topples—how the class system Taylor is writing about, with its injustices, topples. Ultimately, this is because of pride (one of the Seven Deadly Sins) and simple fear, as well as the couple’s passivity regarding the unfairness of the old order. The story is an indictment, not merely a display of race relations and the class system’s inherent unfairness. It’s a protest story. And it’s anguished.

LOA: A reader of Taylor’s stories soon realizes he’s not the straightforward realist he initially seems to be. Your introduction mentions the importance of dreams as a source of inspiration, and there are gothic undertones to some of his greatest stories, like “Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time.” How do you read him?

Beattie: I know I’m being asked to categorize him as a realist, a modernist, or something else, but he just transcends every category, so I’m going to wiggle away.

He wanted to do different things, which included writing in different genres; he knows those genres, so readers will do well to stay alert to echoes of, or allusions to, poetry, and—of course—painting.

It’s helpful to read the stories keeping Freud in mind (to state the obvious, Peter and Freud were emphatically focused on the unconscious). Know mythology. It’s helpful to have historical perspective (though he’ll help you there), and to suspend disbelief when you’re brought into the realm of the occult. Literature talks with other literature. Also, sometimes it jabs at it, for its conventions. (Peter is in dialogue with Henry James, for example, with his ghost stories.) Also, since Peter Taylor is so visual, be alert to the picture you’re seeing that gathers above your head and hovers like a cloud. Obviously, the visuals don’t appear as they do in film, but in his writing bits and pieces accrue until you finally realize what you’re looking at, what composite picture he’s drawn.

LOA: Longtime Taylor advocate Jonathan Yardley argued that the work Taylor did after the publication of 1969’s Collected Stories was actually his best. Do you agree? How does Taylor’s writing change over the fifty-four years covered in these two volumes?

Beattie: It’s human nature to say what we prefer and why; Mr. Yardley isn’t discounting the earlier work, or implying that readers should jump in only for the “best” part. An aside: Peter’s writing method was often to structure a manuscript one way in rough draft, differently when he submitted it (or was asked to change it). He said that every story in In the Miro District was initially written in verse.

The other part of the question is difficult to answer. There were many things in Peter’s early writing (beginning in his college days) that re-emerged in later stories, but by then he was even more adept at a story’s delivery. His perspective on things also necessarily changed. If he says he wrote to discover how he felt about things, he must have had quite a few answers by the time he wrote his later work. The writer’s problem is always to get around not only what you know, but what you think you know. He believed there were covert forces, unforeseen circumstances—that chance and unspoken demands intervened in lives, and that his stories should reflect this. He wrote a “ghost” story for his college literary magazine. He mentioned the occult throughout his writing, but especially in his late collection, The Oracle at Stoneleigh Court, whose title was no accident. One of many things he wondered about was unconscious forces, those we couldn’t control (or could we?), and how those—or certain other systems or belief—might shape lives.

LOA: We know it’s not easy, but can you name a personal favorite among all these stories? And is there one story you would recommend to someone who’s never read Taylor before?

Beattie: Honestly, it depends on when you ask. It was a fascinating undertaking to read or to re-read, at this point in my life, all his stories in chronological order. As with every writer, his stories were not equal undertakings, though writers have to fool themselves in the moment of composition into assuming all writing is equal in intent, in order to get a rough draft.

Today? “The Old Forest” remains a favorite, as does a smaller (in length, and also in breadth) story, “Porte Cochere.” (These stories also speak to each other.) As Taylor has his narrator describe it, the father’s private area of the house in “Porte Cochere” exists in limbo. Read the passage. It’s a wonderful observation about what the writer and the writing process is. Add to that the fact that the son with whom the narrator is preoccupied is named “Cliff.” At one point, the troubled and troubling Cliff confronts his old father: “You play sly games with us still or you quarrel with us. What the hell do you want of us, Papa? . . . Why haven’t you ever asked for what it is you want?” In a larger sense, the direct, yet naive question explains a lot of what Peter Taylor was up to—especially as he considered unanswerable questions that he nevertheless revisited.