Today on News & Views we present a guest feature by Dr. Rafia Zafar, Professor of English, African & African American, and American Culture Studies at Washington University in St. Louis; editor of Library of America’s two-volume anthology Harlem Renaissance Novels; and a member of LOA’s Advisory Council. Here, Zafar reflects on how her proximity to James Baldwin (whom she never met) and their shared New York City background offers insights into the “somewhat jumbled past” underlying her “accomplished adult self.”

By Rafia Zafar

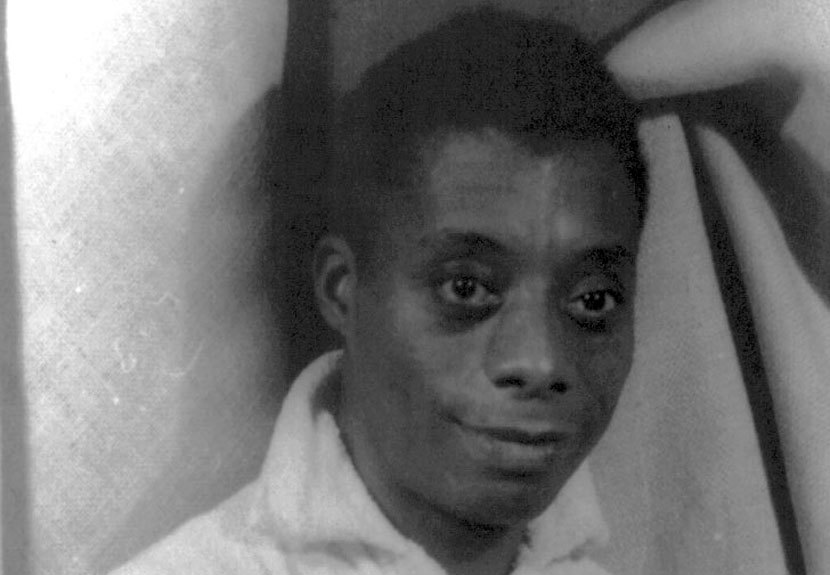

When I think about James Baldwin, I do so not only as a literary scholar and historian but also as a New Yorker. Despite the fact that he lived abroad for the better part of his life, largely in France, and travelled throughout Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, Baldwin was and is very much a man of his earliest years. And although as a scholar I generally travel in the nineteenth century and frequently in locales not my own, twentieth-century Harlem is often on my mind. For me, to think about James Baldwin is to reflect on our proximal lives, to regret my few degrees of separation from him. Baldwin’s pull for me is his powerful, compelling voice; he forcefully modeled a way to write about race and literature, however unattainable that achievement stands. Yet his impact on me is more than that of a literary ancestor. I likely first read Baldwin in my teens; I must have done so at City College, in the class of the late Baldwin scholar Stanley Macebuh. But it is our shared New York—a childhood in Harlem, a high school in the Bronx, young adulthood in Greenwich Village—that links us personally, if tangentially.

First degree of separation. My father Nooruddin Zafar (aka Alfred Walker, Jr.) and James Baldwin were born about three months apart in 1924. For a time my father, like Baldwin, lived with a single mother; my paternal grandparents were married briefly, although they remained legally separated for decades. While my childhood memories of my father’s Harlem apartment were of the large first-floor flat in a building on the still lovely Hamilton Terrace, he also lived for a time in crowded circumstances. According to the 1940 federal census my father and grandmother were boarders on 123rd Street “down the hill,” as my grandmother would later never fail to call eastern Harlem once she was living off Convent Avenue. Wherever my grandfather was at the time they lived on 123rd, he was not listed as resident with them. Like Baldwin, who many times referred to himself as a southerner for having parents who came north during the Great Migration and for growing up among thousands of such migrants, my father too had parents who had journeyed to New York when young. Daddy’s mother was from Virginia, his father from North Carolina. What happened in the period between my grandparents’ marriage in 1924, a few months before my father was born, and 1940 I do not know; neither do I know exactly when mother and son moved “up the hill.”

|

| Harlem Renaissance Novels Edited by Rafia Zafar (2-vol. boxed set) |

Few Harlem boys were admitted to the then prestigious DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, but my father and Baldwin walked its halls at the same time. My father had been enrolled in at least one parochial school, so I do not think he had the serendipity of studying with poet Countee Cullen in junior high school, as Baldwin had. Cullen, member of the DeWitt Clinton class of 1922, wrote a recommendation for Baldwin, whose talents had been evident from earliest elementary school. How my father ended up at Clinton I will never know, for any family members who might have remembered died years ago. Baldwin also recalled being in Harlem Renaissance novelist Jessie Fauset’s French class at Clinton, for after she left her editorial position at The Crisis she returned to her first profession. By the time I would know well the names and works of Cullen and Fauset, my father had passed away. In my teens, like most of my peers, I was heedless of any history but our own and had never asked about my father’s high school days. (Nevertheless to this day I can still sing the first few bars of the DeWitt Clinton fight song; Daddy taught it to his daughters no doubt to counteract the ill effects of the Bronx High School of Science.) If my father had been assigned to Jessie Fauset’s homeroom or had her as a French teacher, I will not learn it from his lips.

Similarly, there was never a chance to talk to my father about James Baldwin, whom he must have known at least slightly. Baldwin and my father would have been two of the few huckleberries in that bowl of milk known as DeWitt Clinton. But by my twenties Daddy was gone and with him a direct connection to so much of what I today study. The chance to have a conversation with Baldwin—we were so close during the 1980s, when he was a distinguished visitor at the University of Massachusetts and I a graduate student at Harvard—evaporated before I had the sense to visit him. Isn’t life a series of missed opportunities? Those conversations that never happened echo more degrees of separation.

The integrated DeWitt Clinton High School offered multiple avenues for self-expression to numerous talented young men. (Clinton became coed in the 1980s.) Among its numerous notable alumni are photographer Richard Avedon, a lifelong friend of Baldwin’s with whom he co-authored a book; artist Romare Bearden; composer Richard Rodgers; historian Ira Berlin; boxer Sugar Ray Robinson. My father, a professional jazz musician during my childhood, was admitted to both Julliard and Howard. The draft, then the bebopper’s life in musically rich Harlem, drew him away from higher education. Baldwin’s early life, scarred by his tenement neighborhood but propelled by an adolescence surrounded by other creative lights, embodies the plight and hope of African America, as he himself knew and wrote of time and time again. His bleak childhood offered the adult author the opportunity to meditate on how his own path, marked so powerfully by want and longing, mirrored countless, unnamed others: No Name in the Street. He gave a narrative to the collective life of countless other Harlem boys. Like my father’s, his career pointed to a path that could be taken if opportunity and luck held out. I can only guess at other similarities in their paths from the streets of the 120s, Baldwin to France, my father “up the hill.” The commonalities I know exist, I just cannot identify them.

Second degree of separation. Sometime in the 1960s, my mother saw James Baldwin in one of the New York airports. Perhaps she astonished him by rushing up to beg an audience. My mother, as I used to joke, was one of the skinny white chicks who married black jazz musicians. She did not think twice about accosting Baldwin to introduce herself and attest to her fandom. She even insisted on an autograph for her younger daughter (me), who she informed him was also going to be a writer. He complied with grace and good humor, she said, yet the thrill was more on her side than mine; she already loved his writing and I had not yet begun to read him. I was merely embarrassed that she shared my secret aspirations with a world-famous author. Maybe that exchange and his handed-over signature did have an impact on my future, however; here I am writing this, after all. Sadly, I lost that piece of paper with his signature long ago. A part of me expects it to turn up stashed in a book or in the back of a file folder. You never know.

Degree of separation unknown. Before I came to love Baldwin as a writer, he was part of my terroir: he comprises part of my New York, black Harlem background. Only recently have I understood how much geography shapes us human animals. Perhaps that’s a function of age, perhaps it’s a side effect from my having lived away from New York City as long as I have. Place shapes New Yorkers as much as prairies or other natural features shape others. As I’ve gotten older this has become more apparent rather than less. Baldwin was born in 1924 in Harlem Hospital; my sister was born there nearly thirty years later. The first version of this essay, in fact, was written in my office at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; as a boy Baldwin roamed an earlier incarnation of the Schomburg, albeit without permission, during its eponymous curator’s lifetime.1 Despite the fact that he lived for much of his life in France, Baldwin was a New Yorker. He claimed Harlem as an integral part of his being, as I and uncountable others do.2

But even beyond the fact of my barely missed-actually-knowing-him relation to Baldwin, his essays spoke powerfully to me from the very first time I read them. Baldwin’s deeply felt and often acrid memories of his childhood in Harlem, even when he writes bitterly about those dark and smelly hallways, resonate with me. My family was never as economically deprived as his was, but I know enough about less than ideal neighborhoods to recognize what he writes about. Rather than bone of my bone, flesh of my flesh, I say plaster of my plaster, stair of my stair: even if what traumas he experienced appeared in my life as little more than frightened peeks at the drug activity across the street or the three locks on our door, his childhood troubles sound my internal resonator. The brief excursions my family had early on into the land of the eviction notice I do not recall; I only know about them from my mother. The sleeping on couches in someone’s apartment I remember better, but they seemed a kind of holiday. When I once asked my mother if we had ever gone on welfare she replied that we could have but “your grandmother would have killed me if I had.” I remember too her saying that she fed us baby lamb chops so we would grow strong and so she skipped meals, smoking cigarettes and drinking Coca Cola. When at one point my sister and I lived with my mother and white stepfather, four in a one-bedroom apartment, we were on the Upper West Side, not in what had become the virtually all-black and largely impoverished Harlem. Then it was a few blocks to Central Park, to the varied stores on Broadway. When I subsequently lived with my grandmother and father it was in the apartment on Hamilton Terrace, dark with its first floor view of rooftops on the slope below us, but secure and clean and big.3 (The Fox lock’s clank dates from those years.)

Baldwin’s essays, then, not only offer me an insight to the existential state of black authors and specifically American blackness, but also and perhaps expectedly into the somewhat jumbled past that lies beneath my accomplished adult self. His essays whisper to me almost/could have been you. Queequeg’s coffin: Baldwin’s memories buoy me so I can tell my own tale.

Iver Bernstein and Katherine Mooney encouraged me to write this essay and offered helpful suggestions early on. Miles Grier and M. Lynn Weiss assisted with their thoughtful feedback.

1. Current Schomburg books curator Associate Chief Librarian Maira Liriano pointed me to the transcript of a former librarian’s oral history. Ms. Augusta Baker recalled: “James [Baldwin] knew how you could sneak up those back steps, and he’d come out in the work area of the Schomburg you see, and then he’d go through, and nobody’s paying attention and here were these wonderful, wonderful books on the black experience, which even then this was the thing in which he was interested. Well then, they’d find him and they’d call downstairs, Mrs. Baker, would you please come up here and get one of your children. I’d trot up the backstairs and say, “James, how did you get up here?!” And he wouldn’t say a word. [I said to] Dr. Schomburg, “Couldn’t we make an exception and let this boy use this collection?”↩

2. My sister, a different kind of expat, has spent the last twenty-plus years in Minneapolis; like Baldwin, she lived in the Village as a young adult. She too considers herself a New Yorker and proudly announces that her birthplace was Harlem Hospital.↩

3. My Bard colleague Myra Armstead reminded me to look again at Manchild in the Promised Land: Claude Brown there refers to the scary life “down the hill” and eventually moves to Hamilton Terrace. My grandmother, having spent time as a single mother boarding with her son on West 123rd Street, obviously felt the same way.↩