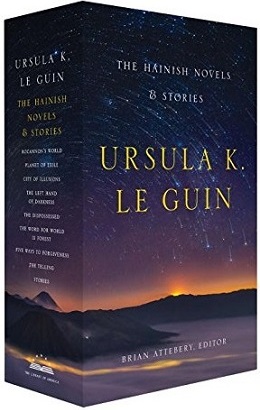

Library of America’s Ursula K. Le Guin edition continues this month with the publication of The Hainish Novels & Stories, a pair of volumes that collects, for the first time, all of Le Guin’s fiction set in the confederation of worlds founded by the planet Hain. In the following guest post, the book’s editor, Brian Attebery, explores the themes and literary techniques that have made these “future histories” such seminal works of modern science fiction.

By Brian Attebery

Rereading Ursula K. Le Guin’s novels and stories of the Hainish universe, collected for the first time in the Library of America’s two–volume set, I was struck not only by how good they are but how important, which is a harder thing to articulate. Why do we need these novels and tales so much? Why do readers emerge from these planetary expeditions with vision refreshed and courage reinforced? Beautiful language helps, and so does simple adventure, but there is some other quality in the storytelling, a pattern that is really three patterns in one.

At the beginning of “The Day Before the Revolution,” a follow-up to her award–winning utopian novel The Dispossessed, the reader becomes aware of a stir in the marketplace: people milling, talking, gearing up for action. A revolution is brewing, but the story focuses on an old woman who sits apart from the disturbance, unnoticed. She is plain, careworn, frail: someone who has seen much and endured more. Utterly unremarkable but unutterably significant, she is one of the characters around whom great fiction is built, like the Mrs. Brown whom Virginia Woolf spotted in the corner of a railway car and began to speculate about. If that were all there was to Le Guin’s story, it would be a worthy piece of mainstream fiction: intensely observed, narrated with elegant spareness. But the old woman is Odo, and the people mustering for revolution are Odonians. She is the source, the spark: she is the revolution. And it is a revolution beyond any in history: a leap to a new language, a new way of life, a new kind of society, a new planet.

Because we believe in Odo the woman, we can envision the possibilities represented by Odo the philosopher: a world without hierarchies, without property, without injustice. Not without pain and friction, of course; in the novel that explores the results of Odo’s activism, there are still people who are petty, short-sighted, vindictive; or, like Shevek the protagonist, too idealistic to settle even for a partially achieved utopia. Shevek allows Le Guin to solve the perennial problem that plagues utopian writers: that of writing an interesting story in an ideal world. Shevek, like Odo and like most of Le Guin’s protagonists, is someone who sees what others don’t. Since he is a scientist, his different way of seeing results in a revolution in temporality, the physics of time, and in a device that can communicate instantaneously across vast distances, the ansible. That, in turn, changes not only his own world but the entire collective of worlds that in Le Guin’s future history is known as the Ekumen.

In another segment of that future history, the novella The Word for World Is Forest, an aggressive force from Earth is exploiting a planet called Athshe, destroying in the process the culture and way of life of the native peoples. One of those Athsheans, a gentle dreamer named Selver, learns the terrible lesson of killing from the invaders after his wife is raped and murdered. He brings this knowledge to his tribe, who are thus able to resist destruction. Selver becomes, according to his people, a god: “a changer, a bridge between realities.” It is a dire fate, but a necessary one if the world is to go on. Many of Le Guin’s central characters are gods of this sort: dreamers who carry their dreams into reality. Their godhood is partly an accident of living in the midst of turmoil and transformation but also partly a result of their being open to the world and alert to its currents.

Odo sees how property binds us. Shevek sees how we construct time even as we move through it. Selver sees that dreaming has a power of which his enemies are unaware. Rolery, in Planet of Exile, sees that her people and Jakob Agat’s are both human and that he is thus someone she could love and be loved by. Estraven, in The Left Hand of Darkness, is the only person on Gethen who sees that Genly Ai, the lone agent of the Ekumen, represents the future. Seeing what is real, they also see how their worlds might be rearranged to form new and possibly better realities. Characters like these are the first part of Le Guin’s threefold method: strong, flawed, believable visionaries in whose wake nothing is the same.

But what of the worlds through which these world-changers, these gods, pass? The many planets seeded by the ancient people of Hain vary widely in terrain and social structure. Rocannon’s world, in the very first Hainish novel, is a romantic landscape of forests, fortresses, and ruins. Werel, in the second, is characterized by extremely long, violent swings of season: decades–long summers giving way to lifetimes of winter (likely the inspiration for George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire). Our own Earth is, at different times in these stories, an almost-destroyed ecosystem or a renewed wilderness of forest and prairie. The Left Hand of Darkness is set on a planet of ice and snow, with a small belt of chilly but habitable terrain between the poles—and a human population whose reproductive biology forces us to rethink every assumption about gender and sexuality. The Dispossessed gives us twin worlds, one lush and the other arid, and at least two competing visions of justice. In later stories we visit mountainous O and slavery-plagued Yeowe and enterprising Aka and ancient Hain itself. What the non-reader of science fiction might not pick up on is that these are all corners of our own world: possibilities in the here-and-now. These many worlds and the divergent social systems we find on them are all based in earthly experience.

So when Odo changes her world, she is also changing ours. There is a reason that Le Guin’s Hainish science fiction is called future history. It has much in common with other historical fiction: with, for instance, Tolstoy’s War and Peace (and with Le Guin’s own Orsinian fiction). Both past and future history help us to see ourselves at a distance, providing just enough strangeness to give us perspective. And unlike fiction of the contemporary world, they don’t date. We go back to them as our own circumstances change and they tell us new things about ourselves. Or, more precisely, they ask us new questions about who we are and what we think we are doing. Historical fiction asks where we came from and how we came to be what we are, and because our understanding of history continuously changes, the past can be revisited endlessly and fruitfully. So can the future: the kinds of thought-experiments represented by science fiction get new answers every time, but especially when the investigator is someone like Le Guin and the conditions of the experiment include a meticulously built environment that resists change even as her characters insist on it.

The third essential element in Le Guin’s method, along with a concretely imagined world and a world-disrupting visionary, is a spyhole, a viewing portal placed where we can observe unobtrusively. Our narrative guides skirt the big public spaces and take us to where the characters live their lives. We meet powerful figures when they are, as it were, off-duty. The stories rarely focus on the battles and debates through which the old powers are toppled and new systems put in place. Rather, we see people living their lives: keeping house as long as there is a house to keep or laying foundations for a new one when the old is lost. Housekeeping is heroic to Le Guin. Even the Ekumen is a household writ large: the Greek word Oikomene comes from Oikos, a living space. Odo is a revolutionary patterned after Peter Kropotkin and Emma Goldman, but she is also a woman who remembers, regrets, desires, devises, and, most importantly, maintains—her work, her household, and her inviolable self. Hidden within the aging Odo is “the little girl with scabby knees” and the “sixteen-year-old, the fierce, cross, dream-ridden girl, untouched, untouchable.”

The first of the linked stories called Five Ways to Forgiveness, “Betrayals,” introduces another revolutionary, Abberkam, who once led and then betrayed the slave rebellion on Yeowe. But we see him in the aftermath as an exile and invalid, his world-altering gifts squandered. The attentions of a seemingly unimportant older woman, Yoss, give him back his health and his self-understanding. Why tell that story, and keep the rebellion in the background? Because Abberkam is both the world-striding leader and the self-defeated exile. We need both moments to understand him, his pride, his revolutionary movement, and his society. And so we overhear the revolution from around the corner, where Odo sits remembering her childhood. We look back on a slave revolt from the little cabin where Abberkam nurses his resentments. We sit with Shevek as he plays with his young daughter while thinking up the Syndicate of Initiative that will shake up even his radical society. World-altering events grow out of dailiness, and people can be both petty and godlike. In Le Guin’s future histories, all these elements work together—the thought-experimental societies, the world-altering individuals, and the oblique narrative perspective—to create a deeply moving and uniquely significant body of work.