Devotees of American literature have another reason to be grateful to the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City this summer. Simultaneous with its Henry David Thoreau exhibition, which we enthused about earlier this month, the Morgan has also mounted Henry James and American Painting, a biographically rich, visually splendid exploration of the novelist’s lifelong involvement with the visual art of his time.

The exhibition is a cross-disciplinary effort that presents photographs, personal artifacts, typescripts, and correspondence alongside fifty years’ worth of canvases by a number of artists. This inclusiveness seems only appropriate given that the show centers on an unusually fruitful symbiotic relationship between different art forms.

James’s artistic leanings were already evident by the late 1850s, when he was still in his teens and his peripatetic family had temporarily settled in Newport, Rhode Island. His older brother William had begun to study painting with the artist John La Farge, himself recently returned from France; in the way of younger brothers everywhere Henry emulated William in painting lessons before realizing the visual arts weren’t his vocation. But the cosmopolitan La Farge also introduced the James brothers to contemporary French literature (Balzac most crucially), and under his mentorship Henry was able to reach the conclusion he related years later, in Notes of a Son and Brother (1914), as “the dawning perception that the arts were after all essentially one and that even with canvas and brush whisked out of my grasp I still needn’t feel disinherited.”

His entire subsequent career would demonstrate the validity of that insight. As the Morgan’s wall text notes, “In his own fiction, James sought, through nuance, scene, and shaded detail, to evoke his characters almost as a portrait painter would.” On a more literal level, the early novel Roderick Hudson (1875) concerns itself with a young American sculptor in Rome—the first of several artist-heroes in the James oeuvre—and the author also maintained a sideline in art criticism from the late 1860s through the 1880s.

The Morgan exhibition also shows how, in his personal life, James formed a number of lasting close connections with painters, nearly all of them American expatriates like himself: Elizabeth Boott and her husband Franck Duveneck, James McNeil Whistler, and most famously John Singer Sargent, whose work prompted James to declare, in an 1887 essay, “There is no greater work of art than a great portrait.”

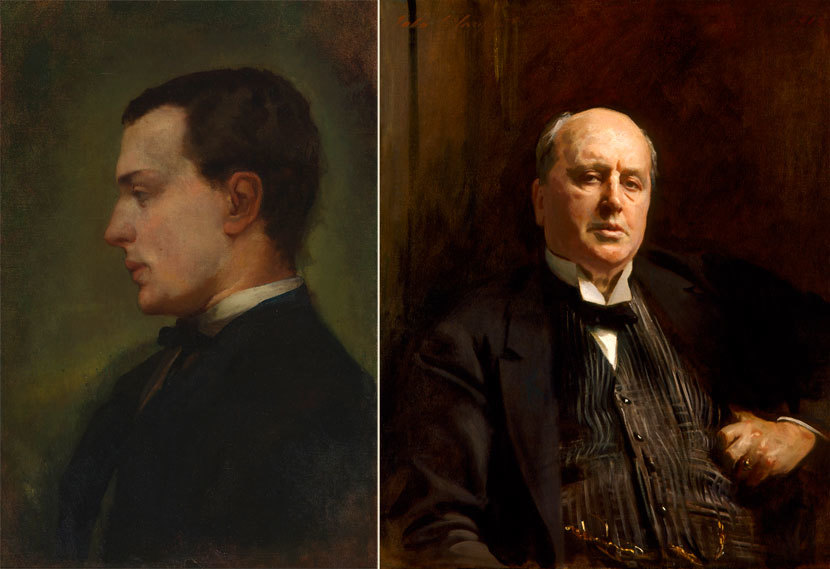

That James’s interest in these and other artists was reciprocated is demonstrated by the number of portraits of him on view, from the unfamiliar bearded figure in an 1881 drawing by Abbott Henderson Thayer to the grandee captured in Sargent’s celebrated 1913 portrait, which was vandalized as part of a political protest at London’s Royal Academy in 1914. (Library of America readers will recognize many of these images from the covers of various volumes in the LOA James edition.)

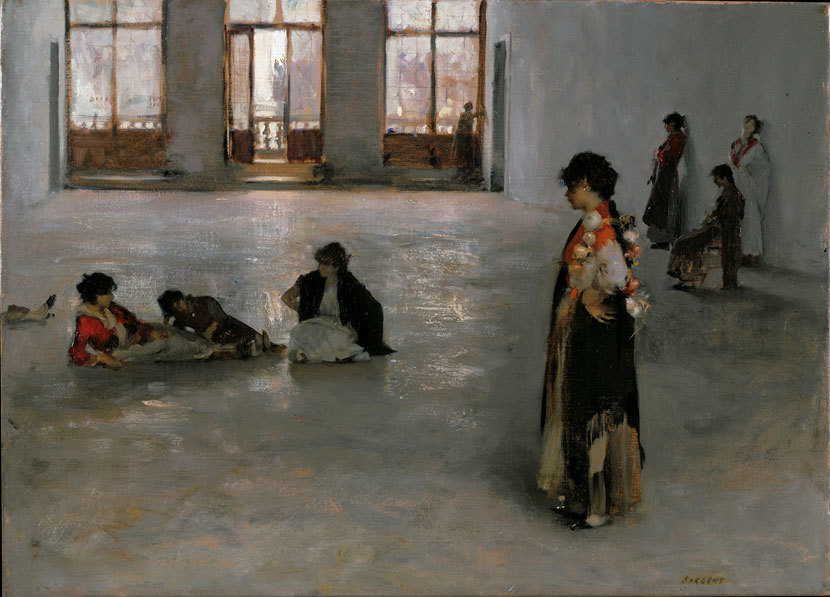

The other paintings on view by James’s artist friends confirm that he had a seemingly infallible nose for talent. A seductive Whistler nocturne; contrasting views, by Elizabeth Boott and Franck Duveneck, of a sun–drenched villa above Florence; Sargent’s magnificent Venetian scenes (both indoors and out)—all these conjure the allure of Europe in varying ways that should speak to any fan of The Portrait of a Lady or The Wings of the Dove.

Worthy of special mention, finally, are the portraits of women in the exhibition. From William Morris Hunt’s Girl at the Fountain (1852–54), with her back turned to the viewer, to Whistler’s spectacular Arrangement in Black and Brown: The Fur Jacket (1872), these portrayals are remarkably suggestive of psychological depth—which is another way of saying that each of them is as multidimensional and as meticulously shaded as a Henry James heroine.

Henry James and American Painting is on view through September 10, 2017, at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City. Visit www.themorgan.org for complete details. The accompanying catalogue, which includes essays by co-curators Colm Tóibín and Declan Kiely, is also recommended.