By Michael Atkinson

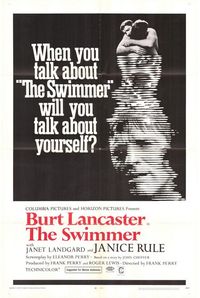

Expanding on John Cheever’s enigmatic short story, and with a genuine movie star as their protagonist, Frank and Eleanor Perry created a haunting parable of the all–American good life and its discontents.

It could’ve only happened in the ’60s—a roiling, electric time of rules rewritten, social roles turned inside out, presumptions and privileges discarded. More than that: culturally speaking, it was an age in which rampant experimentation was fashionable, and truth was pursued by way of crazy psychological expressionism, hard-bitten realism, and a slippery subjectivity (sometimes all at once). John Cheever’s story “The Swimmer” (1964) and Frank Perry’s film The Swimmer (1968) are classic milestones from this cliff-diving renaissance, two complementary works of pitiless all-American existentialism that today look to be, simultaneously, autopsies and prophecies.

Cheever’s “The Swimmer” is a particularly spooky template for class indictment. Its close-third-person mode hews so tightly to its hero’s subjective experience that the narrational voice doesn’t seem to understand it’s fracturing and slipping anymore than Ned Merrill himself does. The story is shaped as a quintessentially modernist pointless journey, the passage of a man through a materialist landscape as his consciousness decays, disconnecting with reality, memory, and time. Eventually it reveals to us, in almost undetectable splats of mid-story disjuncture, how the opulence and familial joy Ned feels at the outset, alongside a strangely euphoric ardor for the summer day and the loveliness of pool water, is in fact dead in the past, and the present is a lost and terrified stumble through the ashes of a failed and empty upper-middle-class life.

| READ THE STORY |

|

| in John Cheever: Collected Stories and Other Writings |

How Cheever manages this Doppler shift is all in his precise and subtle use of language, the mark of a master short story craftsman as much as it is, often, the barrier of entry for filmmakers dazzled by literature. It’s virtually impossible to film subtle rhetorical hints of consciousness and ruminative subjectivity and close-third-person voice, which is why certain modern writers, from Nabokov to Updike to many others, have proven almost impossible to adapt into successful movies. When Robert Altman tried to do it with Raymond Carver, in Short Cuts (1993), Carver’s painfully restrained stories ended up being uncomfortably transformed into nasty comedy. Look at the track record for Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald: what made great twentieth-century writers great, namely their ability to make the prose, and everything it implies and doesn’t say, live in the reader’s head as a kind of prismatic consciousness, is exactly what movies are not made of.

That doesn’t slow some besotted filmmakers down, and it’s easy to see how director Perry and his wife, the screenwriter Eleanor Perry, became gripped by the story’s creepy eloquence. The Perrys, after all, were pioneers of what was becoming, for lack of a better term, the American art film of the ’60s, directly answering the psychological gravitas and thematic ambiguities of Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni with their first two films. The gritty, intimate David and Lisa (1962), about the institutional romance between two disturbed teenagers, got them Oscar nominations, but it was their rarely seen follow-up, Ladybug Ladybug (1963), that presaged The Swimmer’s elliptical structure and sense of despairing qualm, following as it does an an air-raid-panicked elementary school evacuating and scattering across the countryside, convinced nuclear devastation is nigh, though the alarm might’ve been false. Based on a true incident (one girl falls behind, and the class won’t let her into the shelter, dooming her), and doggedly ambivalent about nearly everything—focusing on the post-Cuban Missile Crisis paranoia and not the Cold War itself—Ladybug Ladybug established the Perrys’ fascination with metaphoric journeys and collapsing certitude. They pursued this classic postmodern vibe after The Swimmer, either together or separately, in Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970), The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun (1970), The Deadly Trap (1971), Doc (1971), and the Joan Didion adaptation Play It As It Lays (1972).

What probably doesn’t need to be said is that neither version of The Swimmer could be achieved in today’s culture. Cheever’s acclaimed tale is too mysterious, too densely written, and too ironic-earnest for the first-person-voice, glib-tragic fashions of today’s short fiction, while the loopy, pathological film, made with an honest-to-God movie star bearing a twenty-year pedigree (Burt Lancaster), is as far from a twenty-first-century Hollywood movie as one can imagine. Back then, the projects’ incisive rip through upper-middle-class social structures was standard, but the sense of inherent lostness, and the lean metaphorical conception that expresses it, has an almost dizzying toxicity that would undoubtedly prove too strong a drink for modern multiplex stomachs. Today’s culture doesn’t seem very invested in showing us the mind-bending destitution of our commercialized, conformist lives—indeed, Cheever’s and the Perrys’ diptych plays a kind of prelude to our current dystopic whorl, where we blissfully communicate almost entirely through advertising-jacked electronica, intensely conflate our identities with gadgets and brands and commercial styles, and live in a hyper-mediated bardo state between what we think is real and what we’re not sure is completely virtual.

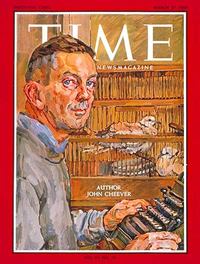

Writing as one of the godheads of the golden age of American fiction, when he served on the board of The Way We Live Now alongside Updike, Mailer, Pynchon, Vonnegut, Barthelme, Roth, Bellow, et al., Cheever possessed a paradigmatic vision of a particular slice of the postwar culture: the complacent, hard-indulging affluent bourgies of the outer urban suburbs, with their brick mansions in the woods, their catering-service parties, their scrupulous insulation from middle and lower classes, their complementary priorities of high-earning day work and compensatory boozing, their bone-deep sense of entitlement, their strict codes for inclusion, their neglected children, and, of course, their elaborate in-ground swimming pools. He trained his vision on this human zoo just when things got interesting—when American society was riven, to an unprecedented degree, by all-out generational conflict. The turning point was, quite naturally, World War II, which left an entire up-and-coming generation disillusioned about the sociopolitical world, the mayhem their own parents were capable of mustering, and their complacent privilege in the years thereafter. In just a decade’s time we had the emergence of youth culture, with all its attendant fury and hunger for radical change, a phenomenon that proliferated until it faced the reality of another and far more unnecessary war, and exploded into an authentic Zeitgeist, changing American institutions, social norms, media, art, and literature forever.

Like many writers, Cheever was fascinated not by the youthful ramparts of those years but by the “normal” aging America in the crosshairs—the moral squalor of the white ruling class, having earned its props during the war and now standing in what they thought was the world they’d made, stupefied by the changes around them and by their own empty priorities. Cheever, as a child of high-born Massachusetts who saw both wealth and humiliating poverty in his youth, and thrived on the fringes of serious New England wealth in the middle century, knew the milieu well. (He knew the seductions and consequences of indulgent everyday drinking, too, as only a handful of novelists did on his scale.) Casting a gimlet eye on these cosseted, super-privileged, self-destroying pure-breeds, from the perspective of the younger set (even if, as with Cheever, the rebellious youth’s point of view was the implied default position, which it still is today), was one of the era’s great spectator sports, and many of the great films of the ’60s–’70s, from The Graduate to The Godfather to Two-Lane Blacktop, play variations on the theme so well it’s how we see ourselves looking back.

Lancaster’s pivotal presence feels organic, too. Alongside his run of big-budget westerns and swashbucklers through the ’50s and ’60s, many self-produced, he had evolved into one of the most progressive and adventurous stars in Hollywood, often taking on unconventional films that directly attacked the conservative establishment (and frequently playing the evil power-monger himself), including Sweet Smell of Success (1957), Elmer Gantry (1960), Seven Days in May (1964), Lawman (1971), Scorpio (1973), and Executive Action (1973). Lancaster’s career was built upon his athletic energy and poised strength, but he knew as few stars did how thin his own box office persona and how ephemeral his stardom could be—anxiety and neurosis boiled right below the broad-shouldered, big-grin surface.

In The Swimmer, Lancaster certainly “got” Ned’s swimming euphoria, described so intensely by Cheever, but in making what’s whimsical and interior in the story so overt and physical—so Lancasteresque—he nudges the film immediately into a strangeness the story reserves in its back pocket for its last third. During the opening credits we see Ned running through the woods in only his tight swim suit: Where is he coming from? How long has he been running? Lancaster’s stylized delivery of the dialogue, all teeth and showy gestures, as he stands practically naked in front of Ned’s secretly uneasy neighbors, tells us right away something’s off. The plan to swim “across the county” through a long series of his neighbors’ pools isn’t an indulgent man’s lark, as it is at first in Cheever. Already at the movie’s outset it has the air of dementia, a lost man’s defensive fantasy breaking into his waking life and obliterating his grip on reality.

The perfectly rancid Marvin Hamlisch score—his first—may be the film’s biggest Hollywood hurdle. In every way the film is necessarily more concrete than the story, and the Perrys compensated for the loss of Cheever’s enigmatic narration, and its impressionistic suggestions of temporal confusion, in fascinating ways. Ned Merrill does seem to appear out of nowhere—out of his muddled ideas of his own life. Only through exchanges with the neighbors do we slowly glean fragmented awareness of the recent past he refuses to acknowledge. Ned’s relentless, oblivious good humor is a symptom of his pathology, born out of a familial cataclysm he can’t remember: debt, infidelity, domestic implosion, bankruptcy, abandonment. Different neighbors know different gossipy tidbits of the Merrills’ demise; when he tells one couple he’s “swimming home,” the wife mutters, “Why would he want to do that?” Some—the cheeriest and the drunkest—know nothing more than the fact that Ned’s been away for a while. (Has he escaped from somewhere, like the hospital in David and Lisa?)

The neighbors and their connections to Ned get fleshed out with expository details, and he has a prolonged dalliance with Janet Landgard’s bikinied co-ed, who thinks he’s kidding her with his high talk and promises of babysitting work (she knows his kids are grown, but that’s all she knows). Some of these moneyed New Englanders—including, at the end of the river of pools, Janice Rule’s bitter ex-lover, who apparently lives outside of the town’s ring of gossip—see clearly that Ned has turned a curve somewhere and has essentially gone mad. The home he’s swimming to is, of course, in the unforgettable ending, locked, dark, foreclosed, and cobwebby with desertion for who knows how long. The life he thinks he’s rapturously swimming through is gone.

Whatever the film had to invent to accommodate its own movieness, it retains the story’s grimmest emotional torque—the sense that Ned’s nightmare is the real-time trial of every parent, who daydreams about his or her family being perfect and contented even as the children grow and leave, the idyll vanishes, and aging starts to darken the day. (One of the film’s posters blared the tagline, “When You Talk About ‘The Swimmer,’ Will You Talk About Yourself?”) Time does not literally shift in the film as it seems to in Cheever, but the single day we spend with Ned, loping down driveways and across lawns like an Olympic track star, does get rainy and cold and oddly autumnal. Visually, when it’s not indulging in ’60s sunbursts and slo-mo, the film is imbued with the dream-like terror of getting stranded, near-naked, far from home, and this is nowhere more intense than when Ned must travel the length of a public pool crammed with lower-class patrons, a nuclear metaphor for American class inequity and as arduous a passage as the ritual-with-flame pool-crossing in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983). It’s in Cheever, but the visible-material existence of the scene on film, as with Lancaster’s imposing demigod frame, does something even Cheever’s prose can’t: it creates a tangible and universal experience we therefore cannot dismiss. What literature does in our heads, privately, cinema does in the room, totemically. It’s possible to read the story as one man’s psychological tribulation, but the film is about an entire generation of mystified American men.

The Swimmer had a famously troubled production. Hot on the Perrys, Columbia Studios and producer Sam Spiegel agreed to the pet project without, it seems, quite understanding it. (“What the hell does this mean and who the hell would want to make it?” one studio executive was reported to have said after reading the script.) Battles ensued, with Frank Perry being fired and newcomer Sydney Pollack being brought in for reshoots (these include many of the film’s more ridiculous chunks, including the slow-motion run around the horse track, set to Hamlisch’s cowboy-song jingle). Spiegel literally demanded a happy ending, but Lancaster and Eleanor Perry held firm, and Spiegel—the three-time Oscar-winning bulldog behind On the Waterfront (1951), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962)—yanked his own name from the credits. In the end, Columbia got fed up and pulled the plug on the production, forcing Lancaster to pony up his own funds to pay for one last day of shooting.

It’s something of a miracle that the Perrys’ and Cheever’s vision is still there—an uneasy wail of existential angst, echoing through the fading Eden of a society adrift in its own privileged muck. Even in the late ’60s, when dying studios like Columbia were beginning to let filmmakers try anything to seduce ticket-buyers away from their TVs and back into the movie-houses, audiences and Industry suits alike had no idea what to make of this strange, moody beast of a film. Today, the movie feels very European in its courageous trust in metaphors and enigmas over narrative clarity, but also anchored in Cheever’s all-American soil, making it a puzzling cult item to new viewers, and an authentic and revelatory freak from the days when movies’ risks and truthfulness mattered most.

Video: YouTube Movies trailer for The Swimmer (1:41)

The Swimmer (1968) Directed by Frank Perry. Screenplay by Eleanor Perry. With Burt Lancaster, Janice Rule, Janet Landgard, Joan Rivers, Kim Hunter, Marge Champion, Charles Drake, Diana Muldaur, Cornelia Otis Skinner, and Diana Van der Vlis.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Google Play • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Michael Atkinson writes about film for The Village Voice, In These Times, Sight & Sound, The New York Times, Brooklyn magazine, Criterion, Turner Classic Movies, and elsewhere. His seven books include Flickipedia: Perfect Movies for Every Occasion, Holiday, Mood, Ordeal and Whim (co-written with Laurel Shifrin), and the novel Hemingway Cutthroat from St. Martin’s Press.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.