Spanning several decades, reaching from doo wop to hip hop, Library of America’s newest anthology Shake It Up: Great American Writing on Rock and Pop from Elvis to Jay Z compiles a “top fifty” of the most outspoken and personal voices on popular music.

Established names like Greil Marcus and Eve Babitz appear in rotation with a younger generation of writers—among them Jessica Hopper, Kelefa Sanneh, and Chuck Klosterman—all of them investing their own work with the same freshness, inventiveness, and often unruly energy that distinguishes the music they write about.

Though the earliest piece in the collection dates from 1963, editors Jonathan Lethem and Kevin Dettmar note in their introduction that “The horizon here is still too near for panoramic views. . . . It’s too early for canon formation in a field so marvelously volatile—a volatility that mirrors, still, that of pop music itself, which remains smokestack lightning. The writing here attempts to catch some in a bottle.”

Jonathan Lethem is the author of ten novels, including A Gambler’s Anatomy and The Fortress of Solitude, and sits on Library of America’s Advisory Council. Kevin Dettmar is the author of Is Rock Dead? and editor of The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan. Via email, Lethem and Dettmar shared some of the editorial thinking behind Shake It Up.

LOA: In your introduction you write, “We’ve assembled a collection of American rock and pop writing—not writing about American rock and pop.” What’s the distinction?

Kevin Dettmar: As befits a Library of America volume, the writers here are all Americans. But the coverage is not restricted to American music. An anthology attempting to represent the richness and variety of writing about American rock and pop would look rather different. We took our assignment to represent the best American rock and pop writing very seriously; and when we had a choice—which Ellen Willis piece to run? How best to represent Robert Christgau?—we tried to select pieces (all other things being equal) that touched on different parts of the rock and pop world. It would have been pretty easy, for instance, to have all the writing here focus on Dylan and the Beatles and Madonna. But as a representation of different genres and scenes in post-war American popular music, this anthology would be wanting in several ways.

Jonathan Lethem: Of course, this gives us a chance to acknowledge that the history of this writing is as mixed up as the history of the music, with crucial moments of call-and-response across the ocean. The early U.S. writers were often yakking back at strong voices in UK criticism (a kind of British Invasion effect), like Charlie Gillett, Nik Cohn, and so forth. For what it’s worth, the last really wide survey of this kind of writing, Clinton Heylin’s The Penguin Book of Rock & Roll Writing, in 1992, came from Over There, and rounds up many of those missing voices.

LOA: In these pages LP liner notes, artist profiles, and capsule album reviews rub elbows with memoirs and more straightforward critical essays. Why the unusual variety of literary forms?

Dettmar: Exciting rock and pop writing comes in all different shapes and sizes. Some great writers, like Greil Marcus, are best known for long-form writing: the book seems to be his natural métier. Whereas (to pick on him again) Christgau’s only books are really just collections of his shorter pieces. Marcus is rock writing’s Dickens; Christgau is its Dorothy Parker. Both have their readers, and their spheres of influence.

Lethem: There’s a semi-fugitive quality to the development of a field of writing about this ostensibly ephemeral music. It emerges in zines and liner notes, in writings on other musical forms, in academia, and in “lifestyle” reportage. We wanted to reflect that constellation as much as possible.

LOA: We’re curious to hear what distinguishes this American rock and pop writing as writing. What were these writers trying to do that hadn’t been done before, for instance, and where and how did they succeed?

Dettmar: Like all popular writing about new entertainment forms, this writing, especially in its early years, had two pretty demanding tasks. First, writers had to argue that their subjects were worthy of serious consideration. A great piece representing this agenda was written by one of the founders of the Library of America, Richard Poirier—his piece called “Learning from the Beatles.” No one writing about the Beatles today would feel the need to defend that choice—which allows Devin McKinney to soar as high as he does in his book Magic Circles, from which we’ve published an excerpt.

But having established the bona fides of the music in question, the writing also has to give us a way to listen to it, a way to hear it. The best of these writers describe with real urgency—and without being too cloying or self-aware—what it is they hear when they listen, and what we should listen for. They teach us how to love it when it’s worth loving, and how to know what’s worth loving, what’s not.

Lethem: All this that Kevin says. And on top of it, in the case of what we’ve gathered here, we were honestly responding to these writers’ ambition, even if it’s hidden in modesty or kidding. That’s to say, their successful desire to deliver what you’d want from any piece of writing, those least quantifiable virtues making baseline conditions for writing worth rereading: voice, mystery, surprise—the sound of a mind discovering some new bit of sense or sensation.

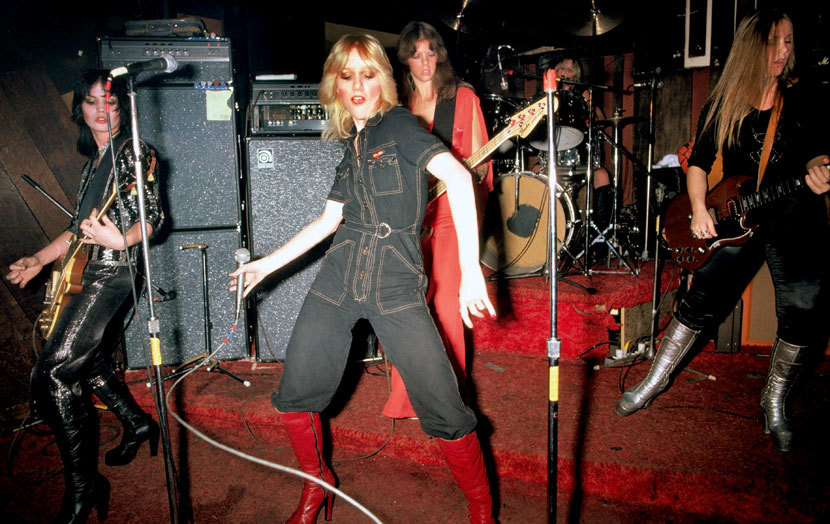

LOA: Shake It Up traces a lineage of women writers in the field, from Ellen Willis through Jessica Hopper and a number of names in-between. Was that something you set out to do, or did the story emerge in the editing?

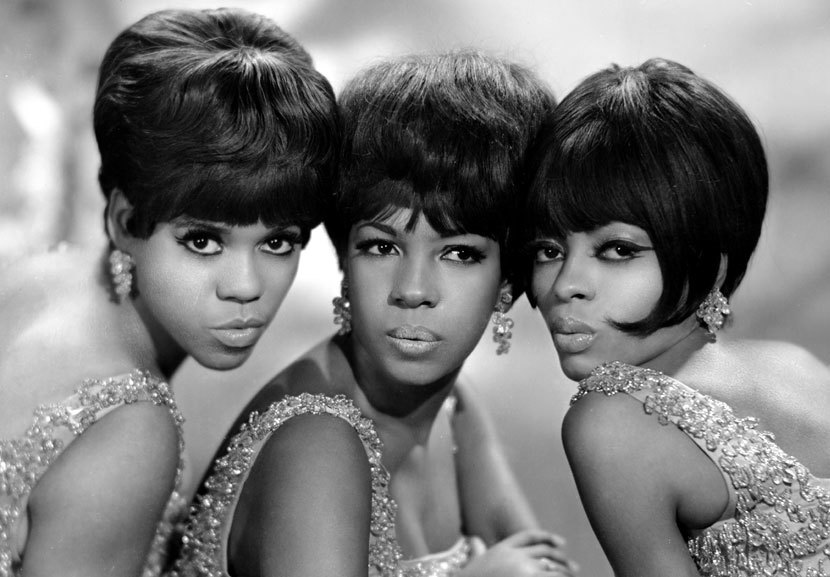

Dettmar: I’d say a combination of those two dynamics. There’s no way around the fact that rock writing, in its early years at least, was a boys’ club: even Ellen Willis got her famous first assignment, writing about Dylan for Cheetah, because her lover Robert Christgau didn’t want the job. But there’s a dude’s-eye view of the music (both exemplified by and sometimes parodied by Lester Bangs) that, for me, palls pretty quickly. Women’s rock writing isn’t worth including just as a palate cleanser; because they have been so systematically marginalized by the androcentric structures of the industry, women rock writers often appear on the scene as fresh eyes and fresh ears. They’re able to identify interesting things that the lads have forgotten how to hear or didn’t hear in the first place.

Lethem: Listen, it would be playing dumb not to admit we set some high (and, in fact, impossible to meet) thresholds for representation when we began this work. What’s happiest to report is how the search, which began practically in a panic, given the dire state of the field for so many years, led to such awesome discoveries. I mean: Lillian Roxon! Plus, it was very generous of Jessica Hopper to become so prominent during the time we were sweating over this contents page (or maybe I mean it was really clever of us to take so long to get this book together).

LOA: In this book we go from the heyday of the vinyl LP and 45 through compact discs, downloads, and now streaming. How has writing about popular music reflected changes in how we listen to it?

Dettmar: That’s a smart and complicated question, one I haven’t thought enough about to provide a really good answer. But one obvious way that the format of the music is affecting the format of the writing shows up in the trend in the past few years for the biggest acts—Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, Radiohead—to drop new albums, unannounced, on a streaming service. So that Lemonade drops on April 23, 2016, and a lot of smart and talented writers essentially stay up all night with the record on “Repeat” and, bleary-eyed, hit “Send” on their “hot take” to their editors early the next morning. I understand the pressures that have driven artists to this kind of extreme tactic, but it’s just brutal on writers, and certainly isn’t conducive to producing thoughtful, measured criticism.

Lethem: There are two different moving targets here: how the music lands in our lives, and how the world wants to find (and pay for) written responses to the music. Could anyone have forecast either the “Amazon comments section” (everyone’s a Christgau!) or the onset of the 33 1/3 series (let a thousand Greil Marcuses bloom!)? I like the suggestion that there ought to be a Pandora for criticism: “After assessing your iTunes, the critical service will write about your taste, so you’ll know you have one.”

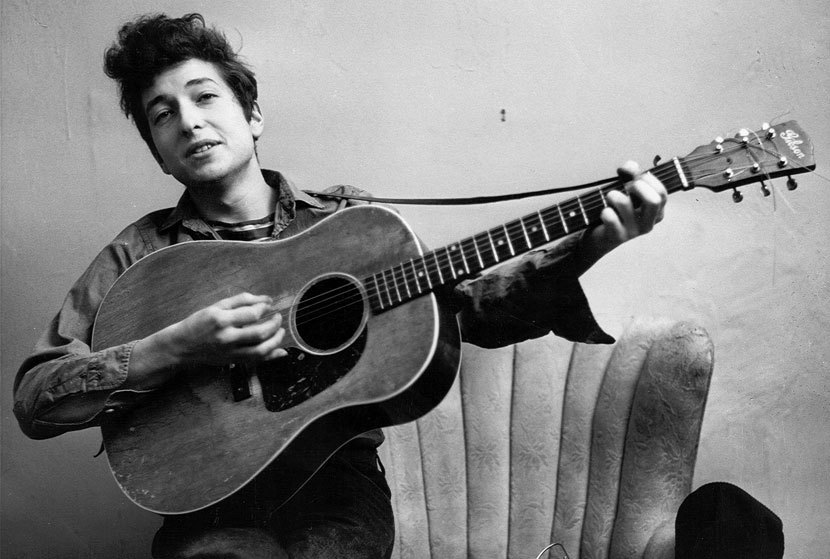

LOA: Bob Dylan is the subject of the first piece in the collection, by Nat Hentoff in 1963, and of another one by Luc Sante, more than four decades and four hundred pages later. Is Dylan the inevitable prominent figure in an anthology of this kind?

Dettmar: For better or worse, yes. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that one could assemble a very credible version of this anthology in which all the writing is about Dylan. (Indeed, under other auspices, it’s been done.) In Dylan, all the energies of literary studies, as it metamorphosed into cultural studies, found its perfect subject. As classrooms from junior high through the graduate seminar felt the urgency of incorporating smart works of contemporary popular culture, Dylan’s literate and poetic work was right there at the ready. (Nobel Prize in Literature, right?) It’s also the case that Dylan and rock writing grew up together, and spurred one another on to new heights. (Though this may have come to an end: much of the writing on Dylan’s recent albums strikes me as sycophantic rather than genuinely critical. Now that he’s an idol whose career spans two or more generations of writers, he seems to have been declared off limits in some quarters for really incisive criticism.)

Lethem: And yet he declined to blurb our book. Sad!

LOA: We know it’s not easy, but can each of you name a favorite piece—a “desert-island-disc” track, as it were—in the collection? What makes it your favorite?

Dettmar: Part of what’s tricky about this question is that some of these pieces were written by friends, and writers who have become friends in the process of thinking about and making this book; so it’s not just an abstract question, but something of a personal one. But the first piece that comes to mind when you ask this question is the short selection from Gina Arnold’s book Route 666. The writing is so alive and immediate and confident and sensual; I first read the book just as I was getting to know Nirvana’s music, and the two—those records, and Gina’s writing about her experience of the band and their music—are ineradicably fused in my mind. I’m tempted to mention two or three other selections that immediately spring to mind as strong contenders for the top spot—but I guess I’ll adhere to the strictures of the question.

Lethem: Aw, crap. Devin McKinney’s excerpt makes the hair on my neck stand up every time I read it again: a piece not about overthinking the Beatles, a mode which it both indulges and critiques, but about right and wrong ways to overthink the Beatles (or anything), and what might be at stake. It treats one of my favorite subjects: how responding to art can induce a kind of paranoia, and whether or not that’s a good situation for anyone at either end of the connection.

Then again, if I could steal one sentence from the book to call my own, it might be Dave Marsh’s effortless and insouciant, “Sometimes I feel that Smokey Robinson raised me from a pup.”