By Tom Nolan

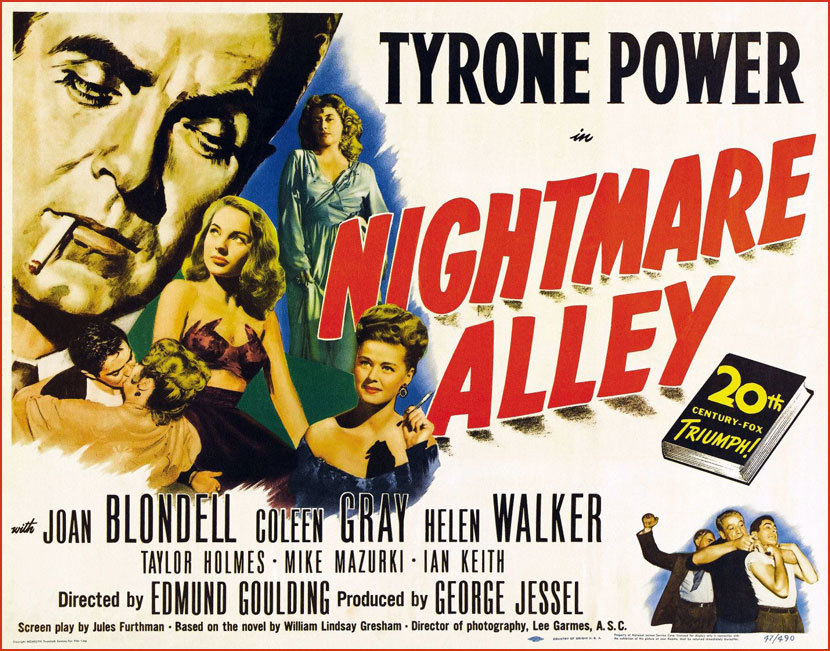

Though it skirts the abysmal depths of William Lindsay Gresham’s original novel, this 1947 adaptation—an unlikely vehicle for leading man Tyrone Power, in a career–best performance—is a remarkable study in depravity and diseased charisma.

Where is Nightmare Alley?

It’s an existential place: a surreal metaphor of a black passageway where a dreamer, chased by an unseen menace, runs and stumbles for his life towards a distant receding light . . .

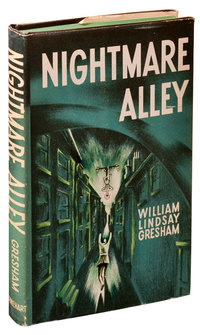

Stan Carlisle is the man with this recurring panic-vision: an ambitious carnival magician and the anti-hero of a grotesque, unforgettable 1946 novel, Nightmare Alley, by William Lindsay Gresham (1909–1962), which was adapted for a dark and damned–memorable 1947 movie starring Tyrone Power.

On page and on screen, Stan is slick, mean, and manipulative: a young man on the make, bound to go places and get rich on the fears and hopes of the “chumps” and “johns” and “marks” he exploits. “Nothing matters in this goddamned lunatic asylum of a world but dough,” the book’s Stan declares to an icily beautiful psychiatrist (is she really a shrink?) who reminds him of the mother who betrayed and abandoned him. “When you get that you’re the boss. If you don’t have it you’re the end man on the daisy chain. I’m going to get it if I have to bust every bone in my head doing it. I’m going to milk it out of those chumps and take them for the gold in their teeth before I’m through.”

Film and novel both open on a small carnival, the Ten-in-One Show, in full daytime tilt. Gresham paints the scene with words: “The ‘marks’ surged in—young fellows in straw hats . . . a fat woman with beady eyes . . . the gaunt woman with the anemic little girl. . . . It was like a kaleidoscope—the design always changing, the particles always the same.”

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s & 40s |

The filmmakers enlarged this kaleidoscope-picture into a down-home panorama as rendered by Thomas Hart Benton: rubes and hicks, harsh prairie beauties and slack-jawed housewives, gum-chewing harridans and wide-eyed kids, all shuffling along the midway eager for whatever sensations present themselves. Here for instance is Mademoiselle Zeena: the wised-up, good-hearted fortune-teller (played by Joan Blondell); Bruno the strongman in a leopard-skin loincloth (Mike Mazurki, in the same year he portrayed Moose Malloy in the film of Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely, Murder, My Sweet); the fetching but naïve young Mamzelle Electra (Coleen Gray)—she wears a flimsy, flesh-clinging costume while static blue fire shoots from her fingers: “only by wearing the briefest of covering can she avoid bursting into flame.” There’s Stanton the magician (Power), handsome sleight-of-hand artist. And then there’s the geek—a bedraggled specimen of savage humanity who bites the heads off live chickens: “Folks,” the carny’s owner intones, “I must ask ya to remember that this exhibit is being presented solely in the interests of science and education.”

From this strange loam Stan will grow his poisoned fortune. He beds the married Zeena, then gains access to her alcoholic husband Pete’s old work-notebook, a treasure trove of mental-act insight: “All have the same troubles. They are worried. Can control anybody by finding out what he’s afraid of.” Stan covertly feeds the drunken husband a forbidden extra shot of booze, which turns out to be wood alcohol: a fatal accident (wasn’t it?). Having learned what he needs from Zeena, Stan wins the heart and faith of Molly (“Mamzelle Electra”); the two leave the carny and work a supper-club circuit with a mentalism act: Carlisle has become The Great Stanton.

They do well, but not well enough for Stan. The “big-time” doesn’t give him peace of mind—or nearly enough money. Sad and wretched memories of his childhood (revealed in the book’s flashbacks, along with the backstories of Molly and other characters) torment him. Tarot deck figures—The Fool, The Magician, The Devil, The Princess—stand sentinel at the top of each chapter: observing, prodding, menacing Carlisle down that nightmare alley.

Humiliated by the condescending treatment of his “high-class” clientele, Stan leaps to an even bigger time with a “spook act” in which spiritualist minister the Reverend Stanton Carlisle helps wealthy old folk speak to their dear departed on the Other Side. “We’ll be doing the marks a favor,” he reassures a doubting Molly, who is to be the reverend’s medium, “we’ll make ’em plenty happy. . . . I tell you, it’s just show business. . . . Pick your crowd and you can sell ’em anything.”

With staged séances and lectures filched from the teachings of “the Masters,” Stan cons his way into ownership of a grand house; and he angles to fleece his richest chump into financing an extravagant temple. Yet bad recollections (including ones involving the death of Zeena’s Pete) continue to haunt him, sending him onto the couch (and into the arms) of a female Chicago “doctor” even more cold-hearted than he. Thus the wheel of fortune spins in a downward spiral for the Reverend Carlisle—the Great Stanton—Stan Carlisle—The Hanged Man.

The writer who produced this extraordinary book, which led to the remarkable film, was writing at the peak of his powers about a world and its characters that had fascinated him for years.

Gresham, born in Maryland to parents who divorced, tall and insecure as a youth, plagued by acne and “weeping eczema” (the poor-man’s stigmata?), felt a sympathetic kinship with the sideshow freaks at New York’s Coney Island. Gresham accepted these people as human beings; just as importantly, maybe, they accepted him. “Perhaps we are all freaks,” he mused, “doing the best we can with the handicaps we carry through the world.”

“He coached himself in the art of conversation,” wrote Abigail Santamaria, biographer of Gresham’s future wife Joy Davidman, “rehearsing like an actor . . . and transforming himself into a smooth-talking raconteur.” In the Depression, he took steps to become a Unitarian minister—not as a con man but to try to do good in the world. Lacking funds for religious training, though, he turned himself into a Greenwich Village folksinger. In the late ’30s, he joined the American Communist Party and went to Spain to serve the Republican cause.

In 1939, Gresham returned to the States, traumatized by his war experience and with a case of tuberculosis. He was hospitalized, in part for emotional instability; throughout his life he’d be prone to depression, which heavy drinking did nothing to alleviate. In 1940, he twice attempted suicide before undergoing psychoanalysis. Meanwhile he began to write—he was intrigued by stories a fellow Spain volunteer had told him of carnival life—and continued to work as a folksinger, appearing at the far-left League of American Writers Fourth Annual Congress in New York along with other artists including Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Burl Ives, and such authors as Richard Wright and Dashiell Hammett.

Also at that conference was another Communist and writer, Joy Davidman. She and Gresham married the following year. “I snatched at love,” Gresham would write, “. . . I snatched at writing . . . I tried to control my own mind by will power. . . .” Davidman’s biographer Santamaria says Gresham suffered “cyclical bouts of insomnia, anxiety, paranoia, and impulsive behavior.” “My mind,” Gresham reported, “was . . . filled with nightmare.”

Bill and Joy had two sons in the course of a rocky union marred by Gresham’s alcoholism, infidelity, and physical violence. At the same time, Gresham continued to seek solace in such disciplines as yoga, Zen Buddhism, Dianetics, Alcoholics Anonymous, and Christianity. Both he and Joy became admiring readers of the English author and Christian apologist C. S. Lewis.

With hindsight we observe that Nightmare Alley was the ideal vehicle for all Gresham’s gifts, suffering, knowledge, intuitions, and preoccupations. Yet books are written in real time, when verdicts are as yet unknown. Back then, it wasn’t even certain the novel would be published.

In late 1944, literary agent Carl Brandt sold Gresham’s unfinished book to Harcourt Brace, with a deadline of May 1945. But in March, the publisher rejected the completed manuscript, for reasons that aren’t clear. Gresham was required to return his thousand-dollar advance. He got a city job and worked long hours to pay his bills and support his family. Meanwhile Bill’s agent placed Nightmare Alley with Rinehart & Company.

Gresham’s drinking increased, and he suffered what he described as “a nervous breakdown.” Both Bill and Joy were emotionally fragile at this time: “They looked to me,” recalled someone who met them then, “as if they were living in a nightmare.”

Then the novel was published to strongly positive reviews, with critics hailing it as a realistic slice of exotica: “a sinister and compelling piece of fiction,” said The Washington Post, “[that will] shock some readers but send the public clamoring to the bookstores.” The Chicago Defender’s Jack Conroy compared Gresham to Nelson Algren as a powerful chronicler of “denizens of the lower depths.”

With ease Gresham reveals the hothouse world of the carnival, with its savvy inhabitants, its us-against-them camaraderie, its rhythmic patter and ballyhoo, its codes of behavior. It’s fascinating to realize the carnie folk think of themselves as being a part of show business—and they are. Stan at one point refers to himself as “a vaudeville actor”; his carny boss urges him to be “a trouper.” The term “grouch-bag” as a storage place for rainy-day funds is authentic show-people nomenclature going back at least to the turn of the twentieth century. One way or another, Gresham knew whereof he wrote.

And when Stan enters the more rarefied worlds of nightclub telepathy and parlor-room spiritualism, the author paints these scenes with equal knowledgeability, describing the medium’s tricks and how they’re achieved, recording Stan’s spiel with a satirist’s accuracy: “My family was Scotch originally, and the Scotch are said to possess strange faculties. My ancestors used to call it ‘second sight.’ I shall call it simply—mentalism.” Stan is so good at what he does, you could almost root for him—but for his loathsome behavior.

With the passage of time, what stands out more clearly is how well the novel is constructed and with what power it’s written. Glimpses into the lives and minds of the carnival’s other acts, and into Carlisle’s marks, are equally vivid and convincing. The psychological insight in Gresham’s novel was no doubt electrified by his psychoanalysis, but it’s summoned by an artist’s wand. A subtle writer who knew the value of “show don’t tell,” Gresham made his most shocking scenes all the more effective for allowing the reader to discover nuances not spelled out.

Nightmare Alley in 1946 came to the attention of movie star Tyrone Power, who urged Twentieth-Century Fox to buy the novel as a starring vehicle for him. The studio paid Gresham $50,000 for screen rights and rushed a film into production for release in 1947.

Fox’s artisans retained and enhanced the book’s fundamental aspects. Cinematographer Lee Garmes (Stormy Weather, Duel in the Sun) and the production-design team gave early scenes the visual look of a Farm Security Administration photographer’s proof-sheet. The male and female leads were seen through a steamy lens that evoked an earthy heat: lots of carnal in this carnival. But the characters moved in and out of chiaroscuro in a noirish dance of shadow and light.

Veteran English-born director Edmund Goulding (Grand Hotel, The Dawn Patrol, Of Human Bondage), who’d just worked to good effect with Power in Twentieth-Century Fox’s picture made from Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge, here guided the leading man through arguably his best career performance, a mesmerizing portrait of seedy charm, facile sincerity, evil ambition, and pathetic disgrace. Several other players are excellent too, including Ian Keith as the down-on-his dignity Pete.

The script by Jules Furthman (whose earlier screen credits included Mutiny on the Bounty, To Have and Have Not, and The Big Sleep) kept much of the book’s dialogue and essence, though many story cuts and compressions were needed. The main departure from the novel came in making Stan less than a complete heel: instead of running out on Molly (in the movie he’s married to her), he gives her all his cash and says he loves her. Thus we’re prepared for a final-scene reunion with its redemptive promise: a “Hollywood” ending at complete odds with Gresham’s last-page leap into the abyss.

The movie’s contemporary reviewers weren’t bothered by its semi-hopeful fadeout, but some were annoyed with its grimy depravity. The New York Times concluded, “this film traverses distasteful dramatic ground and only rarely does it achieve any substance as entertainment.” Other critics were more appreciative. James Agee (who wrote for Time and The Nation), enthused: “This kind of wit and meanness is so rare in movies today that I had the added special pleasure of thinking, ‘Oh, no; they won’t have the guts to do that.’ But they do, as long as they have any nerve at all, they have quite a lot.” A later generation’s premier movie critic, Pauline Kael, was emphatic about the film’s merits, calling it “a tough-minded treatment” and terming “the material . . . unusual and the cast first-rate.” Into the twenty-first century, the movie’s brute force and diseased charisma cannot be denied.

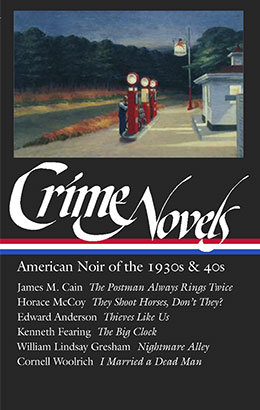

The book’s reputation has soared even higher, with its reissue in an unexpurgated trade paperback and its inclusion in the Library of America’s Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s & 40s (edited by Robert Polito). “For fans of vaudeville and magic, the book is a treasure trove of trade secrets,” promised Walter Kirn in a New York Times review of Crime Novels. In 2010, Michael Dirda in The Washington Post called this “portrait of the human condition . . . a creepy, all-too-harrowing masterpiece” and asked: “Why isn’t this book on reading lists with Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts and Albert Camus’ The Stranger?”

Life was not as kind to Gresham as were the critics. He and his wife mismanaged their movie money, buying a big house but neglecting to first pay their taxes. For the rest of his life, Gresham scrambled to make a living as a freelance writer. In time, he demanded a divorce from Davidman, and she gave it to him—after which she moved to England and married C. S. Lewis (The Screwtape Letters; The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe), with whom she’d begun a lively correspondence; their relationship was dramatized in Shadowlands. Gresham lost custody of his two sons.

At the age of fifty-three, ill with cancer and beginning to go blind, Gresham checked himself into the New York City hotel where he’d written much of his first novel and committed suicide with an overdose of sleeping pills.

Writing the Great American Novel, making a big Hollywood sale: even these archetypal fulfilled dreams couldn’t keep William Lindsay Gresham from plunging down his own nightmare alley.

“Stan, ’fess up,” Zeena asks Carlisle near the start of their acquaintance. “Were you ever really a preacher?”

“That was my old man’s idea once—to make me one,” he answers. “Only I couldn’t see it. Then he wanted me to go into real estate. But that’s too slow a turn. I wanted magic.”

For a while—and still, between the covers of his astonishing book—Gresham had it.

Nightmare Alley (1947). Directed by Edmund Goulding. Screenplay by Jules Furthman, from the novel by William Lindsay Gresham. With Tyrone Power, Joan Blondell, Coleen Gray, Helen Walker, Taylor Holmes, Mike Mazurki, Ian Keith.

Buy the Fox DVD • Watch on Amazon Video

Tom Nolan is the author of Ross Macdonald: A Biography, co-editor (with Suzanne Marrs) of Meanwhile There Are Letters: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and Ross Macdonald, and editor of the Library of America’s three volumes of Macdonald novels. He lives in Southern California.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.