By Sheila O’Malley

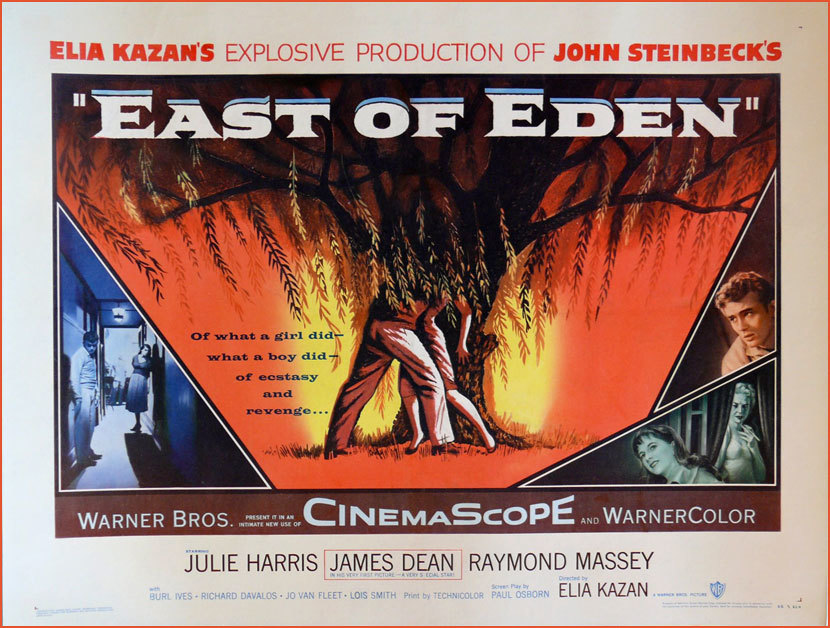

Though the story is severely cut, Elia Kazan’s 1955 adaptation of John Steinbeck’s expansive best seller thrums with the music of the original—partly because of a casting choice that changed American culture forever.

“These people are essentially symbolic people.”—John Steinbeck, journal entry while writing East of Eden

“He’s an odd kid and I think we should make him as handsome as possible.”—Elia Kazan to producer Jack Warner on the casting of James Dean as Cal Trask in East of Eden

The woman in black stalks across the wide screen, her silhouette stark against the landscape. The camera views her from afar. Behind her skulks a lean watchful boy. The visual tension between the two figures keeps the screen in perilous balance. Finally, the camera follows her across a street, and lands on the lean boy, sitting on the curb in the foreground. It’s our first good look at him. It’s James Dean, hauntingly young, with a face described by his director Elia Kazan as “desolate and lonely and strange,” making his unforgettable film debut in (as the credits announce) “John Steinbeck’s East of Eden.”

That impressive credit is evidence of the book’s enormous popularity, but it would be more accurate to say “Elia Kazan’s East of Eden,” since the film—an intricate and cathartic family melodrama/coming-of-age tale—is covered in Kazan’s fingerprints. Kazan was drawn to stories about misunderstood young men going up against father figures and/or society, and that aspect of Steinbeck’s book inspired him. Kazan wrote Steinbeck during the development process, “Eden is the toughest dramatization I’ve ever seen—and for one reason: It’s so rich! There’s so much of it!! Even when you take only the last fourth, there’s much too much.”

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in John Steinbeck: Novels 1942–1952 |

Steinbeck’s first title for the book was My Valley: He wanted to explore Cain and Abel’s legacy on mankind (“the basis of all human neurosis,” he wrote) and also re-create the Edenic land of his childhood, California’s Salinas Valley. Steinbeck is almost as fetishistic in that pursuit as James Joyce was in describing Dublin in Ulysses. You could do a walking tour of Salinas holding East of Eden in your hand. The book is about two Salinas Valley ranch-owning families, the fictional Trasks and the Hamiltons (Steinbeck’s own ancestors) over three generations spanning from the Civil War to World War I. The film focuses on the third generation of Trasks: father Adam and his teenage sons, Aron and Cal. Adam’s wife Cathy took off when the boys were babies and worked as a prostitute for a while before becoming a madam, running the most depraved whorehouse in town. Adam told his sons that their mother died, but restless Cal finds out the truth (this is where the movie begins). Aron is the “good” son, Cal the “bad,” and the boys jostle for their father’s approval, unconsciously playing out their Cain and Abel roles.

A list of what was cut for the film: Adam’s eccentric father Cyrus, the violent relationship between Adam and his brother Charles, Adam’s aimless young manhood, Cathy’s childhood history (which includes killing her parents), and the entire Hamilton clan. Adam’s Chinese American servant Lee, the most important character in the book, is also a casualty. In 1981 there was a three-part East of Eden mini-series, a more comprehensive adaptation. Except for Warren Oates as Cyrus Trask, it’s nearly unwatchable. The mini-series knows the lyrics of the book, but is deaf to the music. Kazan’s truncated East of Eden thrums with the music of the original.

Steinbeck had made his name ten times over with The Grapes of Wrath (1939), but the ambitious Eden nagged at him. He wrote in his journal: “Always before I have held something back for later. Nothing is held back here. This is not practice for a future. This is what I have practiced for.” Steinbeck and Kazan had collaborated together on a film near and dear to them both, Viva Zapata!, a highly fictionalized account of Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, starring Marlon Brando. East of Eden was optioned by Warner Brothers based on the advance galleys. Kazan was attached from the jump. The book became a phenomenon upon publication, perching at the top of best-seller lists for November and December 1952, and into January, 1953.

When Kazan and his screenwriting collaborator Paul Osborn sat down to do the adaptation, they homed in on Cal Trask, slashing away everything that didn’t have to do with Cal’s desire to gain his father’s approval and love. The romantic triangle between Cal and Aron and Aron’s girlfriend Abra becomes peripheral. In a letter to Osborn, Kazan wrote, “Cal is so absorbed in the problem with his father that he can’t really have a girl in any way except for half an hour.” Kazan said in a 1971 interview, “This was really a very personal film, one of the most personal I’ve ever made . . . East of Eden was for me a kind of self-defense. It was about people not understanding me. It was about my relationship with my father, how he disapproved of me all the time.”

From the opening scene, with James Dean lurking behind the woman in black (Cathy, played by Jo Van Fleet in an Oscar-winning performance), Kazan shows his hand: the film will be about that lonely boy, casting shadows twice the length of his body, stalking his parents, both of whom are absent, albeit in different ways. Kazan expressed concern that those who loved the book might be disappointed in what was lost in translation. But the film was a hit, especially with teenagers who took to James Dean’s performance as though they had been waiting for it all their lives. Dean made just three films, East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, and Giant. Only Eden was released during his lifetime.

You didn’t “have to be there” to understand the impact of James Dean on young audiences at the time. I was born much later, but when I saw East of Eden at age thirteen, on late-night television while babysitting, his performance rocked me to the core from the second he appeared. It wasn’t just his beauty. It was the fact that his twisted-up body (which drove—and drives—his critics nuts), and his awkward vulnerability, so enormous he runs away from it at the same moment it bombards him, expressed exactly what it felt like to be an intense teen in a world that didn’t understand.

Six decades later, Dean’s performance, whether he’s dancing through bean sprouts stretching to the horizon (Dean’s idea), flinging his body across the street after a fight with Aron, or collapsing against his father’s chest, still has enormous lyrical power. He is especially good in moments where Cal has a strong objective: wanting to kiss Abra (Julie Harris) while they’re on the ferris wheel (a scene invented by Kazan and Osborn), or bringing Aron to the whorehouse to show his brother what their mother has become. Listen to how Dean pleads in one scene, “Talk to me, father!” That’s how you play an objective as an actor: it’s life or death. Dean’s “mannerisms” may appear “too much,” but the whole film is “too much” and Kazan was smart enough to realize he needed an actor capable of going to that extreme. The result, of course, was that James Dean in East of Eden wasn’t just Cal trying to connect with his father. He became, instantly, Every Misunderstood Kid Everywhere (an identification that would reach its baroque height in Dean’s next film, Rebel Without a Cause). Dean became an archetype of Teen Angst while he was still alive.

The “generation gap” dynamic in East of Eden tapped into a contemporary turbulence when “What’s the matter with kids today?” dominated cultural conversation. The so-called epidemic of “juvenile delinquency” was epitomized in an earlier film, 1953’s The Wild One, starring Brando as Johnny, head of a biker gang. The film includes a famous exchange: “Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” Johnny replies: “Whadda ya’ got?” That rejoinder had terrifying implications to those protecting the Eisenhower Era status quo. East of Eden was filmed in July 1954, the same month a teenage virgin truck-driver stepped into Memphis’s Sun Studio and recorded “That’s All Right,” unleashing a Big Bang of sexual energy that still reverberates today. James Dean’s performance as Cal showed the psychological reasons for all that outer rebellion. Kazan observed during filming, “Certainly there was never such a hero before.”

Raymond Massey plays father Adam Trask as a stern and pious man, a shift from the book where Adam is so devastated by his wife’s betrayal that he walks around in a dream-world, barely acknowledging his sons. In the film, he is a wall of disapproval against which Cal flings himself—literally, in one memorable scene. Richard Davalos (also making his screen debut) plays Aron, the “good” son, although in Kazan’s conception Aron is a smug and petty bore. Julie Harris, as Abra, was the biggest name, although more so with New York theatergoers. An actress who had studied extensively with Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio, she had already won a Tony Award in 1952 for her portrayal of Sally Bowles in I Am a Camera, and would win her second Tony in 1956 for playing Joan of Arc in Jean Anouilh’s The Lark. (Over the course of her career, Harris received an astonishing five Tony Awards and ten nominations.) Significantly older than Dean, she brought to the role, in Kazan’s words, “a wonderful conception of purity and sexual awareness.” There’s a scene in the ice plant where she presses her face up against a block of ice, cooling herself down from the heat of Cal’s presence. She was every teenage girl and gay teenage boy fanning themselves in the dark movie theatres across the land.

Jo Van Fleet is a hard-bitten presence, holed up in her lair, a spider drawing victims into her web. She is not exactly the Cathy in the book, bluntly introduced by Steinbeck with the chilling sentence: “I believe there are monsters born in the world to human parents.” Cathy’s behavior cannot be fully explained, and many critics have rejected her outright, feeling she is too baldly evil to be realistic. Steinbeck insisted he had known a Cathy or two in his lifetime. Either way, Jo Van Fleet’s Cathy is a ruthless businesswoman, a possible drug addict, and a heartless exploiter. (Lois Smith, also making her film debut, is incredibly touching as a girl working in the whorehouse, terrified of her mistress.)

Kazan said of his directing style, “I don’t think of myself as a realist. I think of myself as a poetic realist or ‘essentialist,’ as I call it.” Kazan understood, along with Steinbeck, that the book was essentially symbolic, and he dove into its symbols visually. Warner Brothers insisted that Kazan use CinemaScope, the hot new technology, where the frame was thin and horizontal as opposed to square. Director George Stevens joked: “They finally found a way to photograph a snake.” Kazan did not think CinemaScope was appropriate for an intimate family drama. Close-ups don’t really work in CinemaScope, and individual figures get lost in a frame more appropriate for landscapes and crowd scenes. But Kazan and his cinematographer Ted McCord attempted to use CinemaScope to their advantage. Martin Scorsese observed, “In this movie, the shape becomes dynamic.” They tilt the camera during domestic scenes, giving a queasy sense that the troubled Trask home is a sinking ocean liner. They block out whole sides of the screen so that the viewer’s eye is drawn to the essential. The film is drenched in color and inky-black shadow. There are certain images exquisite in their beauty and asymmetry.

Raymond Massey, a stage-trained professional, was horrified by some of Dean’s shenanigans, onscreen and off. The two did not get along. Kazan, a master manipulator, exploited this clash of styles and temperaments for onscreen sparks. If Dean was Every Misunderstood Kid, then Massey was Every Judgmental Adult. Julie Harris brings out the complexity in Abra, making it clear why this nice girl would be drawn to Cal. And it’s not just about sexual heat. Abra has “father issues” too. She, too, worries she is “bad.” She recognizes herself in Cal. Harris has a way of listening to Dean that is the essence of generosity, and Kazan relied on her to be a lightning rod for Dean’s electric unpredictability.

East of Eden premiered in February 1955, and James Dean’s performance was immediately controversial. The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther referred to it as “histrionic gingerbread.” (A nice phrase, however incorrect the assessment.) Comparisons to Brando were rampant. Crowther scolded: “Mr. Kazan should be spanked for permitting [Dean] to do such a sophomoric thing.” The irony is that there really isn’t much similarity between the two actors, except for a willingness to be vulnerable. A vulnerable leading man was hugely destabilizing to the idea of masculinity and what it should look like. But Brando was all dynamic power and expression, and Dean was all neuroses and repression. It’s impossible to picture James Dean as Stanley in A Streetcar Named Desire, and it’s hard to picture Brando as Cal. The teenagers, boys and girls, who flipped out over Dean didn’t listen to critics arguing amongst themselves. The James Dean Cult had begun. Dean would be dead just seven months later.

In his autobiography, Kazan wrote: “But this I have noticed about people with mysterious gifts: In many cases, a wound has been inflicted early in life, which impels the person to strive harder or makes him or her extrasensitive. . . . These are our heroes, those who have overcome what the rest of the race yields to with self-pity and many excuses. . . . Their precious gifts, for which they paid in pain, have made me successful when I was successful. I’ve relied on their talent; it’s the essence of what I’ve needed most from the race.”

James Dean’s “mysterious gift” is on full display in East of Eden, more so than in his other two films. He vibrates with awareness. Physically, he is fearless. In the scene where his father rejects his gift, just as God rejected Cain’s, the naked agony that pours out of him is excruciating to watch. If you’re embarrassed by his primal scream, then that’s exactly where Kazan wants you. Rejection may not look like that in real life, but it’s what rejection feels like. This is not kitchen-sink realism and Dean was not a realistic actor. The theme of “Steinbeck’s East of Eden” rests on Dean’s sharply-angled slender shoulders. He was more than up to the challenge.

Kazan was known for giving chances to newcomers, like Eli Wallach, Carroll Baker, Maureen Stapleton, Ben Gazzara. He used Brando brilliantly (mainly, he admitted, by staying out of Brando’s way). He took risks on people that paid off magnificently: consider the genius stroke of casting Andy Griffith in the deeply cynical—and eerily prescient—A Face in the Crowd, or casting non-bombshell Barbara Bel Geddes as the sexually suffering “Maggie the Cat” in the Broadway production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. With such a track record, it’s even more striking to hear Kazan’s reflection later in life on James Dean in East of Eden: “It was the most apt piece of casting I’ve ever done in my life.”

Video: 1955 trailer for East of Eden (2:53)

East of Eden (1955) Directed by Elia Kazan. Screenplay by Elia Kazan and Paul Osborn, adapted from the novel by John Steinbeck. With James Dean, Raymond Massey, Julie Harris, Jo Van Fleet, Burl Ives, Richard Davalos, Lois Smith.

Buy the DVD • Buy the Blu Ray • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Fandango Now • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Sheila O’Malley is a film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including Film Comment and The Criterion Collection. She has written two tribute reel narrations for Governors Awards honorees (Gena Rowlands, Anne V. Coates). A short film she wrote, July and Half of August, premiered at the 2016 Albuquerque Film and Music Experience and will screen at the 2017 Ebertfest in Champaign, IL. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.