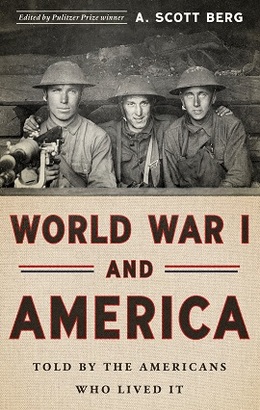

Library of America’s new anthology World War I and America: Told by the Americans Who Lived It collects 127 pieces of writing that trace the entire arc of U.S. involvement in the cataclysm that shaped the twentieth century. Covering battlefront and home front in equal detail, these vivid eyewitness accounts form an unprecedented mosaic overview of the war and its aftermath, offering revelatory perspectives on the conflict whose consequences are still being felt today.

The book’s editor, A. Scott Berg, is the author of a series of notable biographies, including Wilson (2013), an acclaimed portrayal of the twenty-eighth president; Lindbergh (1998), which won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography; and Max Perkins: Editor of Genius (1978), which won the National Book Award and was recently turned into the feature film Genius.

Via email, Berg discussed the choices that went into the new volume and the enduring effects of World War I on American life and culture.

LOA: The writings in World War I and America come from a wide cross-section of Americans: soldiers and civilians, reporters, politicians, pacifists, nurses, and others. How did you decide what to include—and how much of a challenge was it to decide what to leave out?

Berg: Selecting the contents of this book was an enormous challenge, one I would not have undertaken without the editorial advisory board that assisted me—historians Jennifer D. Keene, Edward G. Lengel, Michael S. Neiberg, and Chad Williams, all of whose suggested pieces were combined with my own stack of possibilities. And then Library of America editors Geoffrey O’Brien and Derick Schilling helped me winnow the thousands of pages until we found the shape of the story we all wanted to tell.

I tried never to lose sight of the book’s primary mission: to provide a compelling narrative—the history of the war and its immediate aftermath. Every piece had to advance that story and illuminate a particular aspect of life affected by the war. And, of course, every selection had to gleam with literary value.

LOA: In your introduction, you write that the theme of identity unites most of the pieces in the collection. Can you elaborate on what you mean by that? Does this sense of the word identity resonate with how it’s commonly used today—in the phrase “identity politics,” for instance?

Berg: From the beginning of time, people have questioned their identities—where and how they fit into the world. As I was examining the contents of this book, I noticed that very theme ran through virtually every piece, in one way or another. The period’s rampant nationalism (identity on a grand scale)—exaggerated by displays of military might—contributed greatly to the start and continuation of this unnecessary war. At the same time, alienated minority populations living within vast and motley empires sought to assert their own identities.

The adolescent United States—some fourteen decades old—underwent an identity crisis, with its population gravitating from rural to urban environments. And drawing upon his own identity, President Woodrow Wilson—descended from a long line of Presbyterian ministers—introduced a moral component to American foreign policy. In articulating new ideals by which he believed his country should live, he redefined its place in the world, as he moved the nation from its isolationist posture into interventionist action. With the planet coming apart at the seams, factions of all identities—especially women and African Americans—asserted themselves, seeking their places in the new world order.

LOA: As a biographer of Woodrow Wilson, you’re aware of the controversies that have surrounded his name and legacy in recent years. What role does he play in the story this book tells, and what impressions are readers likely to take away from his many appearances?

Berg: Woodrow Wilson was the dominant personality of the era and its most eloquent voice. A genuine visionary, he sought not a new balance of power, but what he called “a community of power,” built upon a League of Nations—a table at which all countries might peacefully resolve problems before considering war. Readers may conclude that Wilson was either idealistic or naïve, too rigid or too compromising, a genuine savior or a man with a messiah complex; but I don’t think anybody who reads his words and considers his actions can doubt his sincerity.

For me, the most moving selection in the book is his speech at the American Cemetery outside Paris on Memorial Day, 1919. This passionate address bespeaks all that we fought for and the price both he and the nation paid for it. Wherever one comes down on Woodrow Wilson, nobody can dispute that he changed the world.

LOA: In Wilson’s April 2, 1917, address to Congress (included in the book), he states, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” As we know, that sense of mission would become a guiding principle of U.S. foreign policy. What can we learn from encountering it in the context of a hundred years ago?

Berg: I think we can learn where the country was a century ago—an isolationist nation with an army the size of Portugal’s. I consider Wilson’s address to Congress the most important foreign policy statement in modern American history, one that dramatically altered the country’s mission and has dictated practically every American intervention since. His words have been used and abused by politicians from both ends of the political spectrum, as the concepts of self-determination and collective security have evolved into a policy of policing the world. What began as peacemaking has become peacekeeping.

LOA: World War I and America spotlights the role of African Americans in the conflict, both at home and overseas. What makes the presence of black Americans in the war so significant? Is there a particular piece that’s crucial to this topic?

Berg: Fifty years after slavery had been abolished in the United States, the great majority of African Americans remained second-class citizens. Many black men considered the war as a means of gaining full citizenship, a chance to fight on behalf of a country that did not do the same for them. Four hundred thousand Negro soldiers went to war, many giving “the last full measure of devotion.”

But African American soldiers returned to the same conditions they had left behind, or worse; and President Wilson did nothing to rectify that. Bloody riots broke out across the country during what became known as the “Red Summer.” Many African American activists wrote compellingly about this turning point in race relations. Nobody captured—and ignited—the new spirit of the day better than W.E.B. Du Bois in his “Returning Soldiers.”

LOA: More than a hundred pages here are devoted to events that took place after the Armistice of November 1918. How did you decide where the story should end?

Berg: The Armistice marked the end of the fighting but not really the end of the war. Wilson had led the nation into this war, in part, because he felt the United States could write the peace—one that might insure that they had just fought the war to end all wars. But the diplomatic battles in composing the Treaty of Versailles—especially because of Wilson’s insistence upon its including his League of Nations—would affect the world far beyond the four years of massive destruction. It took another three years before Wilson’s never-ratified Treaty had met its demise and his successor, Warren G. Harding, officially ended the war with the Treaty of Berlin. Three months later, the Unknown Soldier was laid to rest, and that seemed the most fitting conclusion to this earth-shattering story.

LOA: The book’s coda introduces three literary responses to the war by writers closely associated with it: Ernest Hemingway, E. E. Cummings, and John Dos Passos. What are these pieces doing in an anthology of nonfiction accounts?

Berg: While this volume celebrates the wealth of nonfiction that emerged during the war, it would have been remiss had it not acknowledged the vast amount of great fiction that was written in its wake. Two decades of some of America’s finest writing—much of it written by what Gertrude Stein named “the Lost Generation”—seemed too important to ignore. I wanted readers at least to remember that many threads of the material in this book would be spun into some of the most enduring fiction ever fashioned.

LOA: Elsewhere you’ve mentioned being pleasantly surprised by Edith Wharton’s accounts of the western front. What else are readers likely to find surprising in this collection?

Berg: I think the quality of the pieces from the nonprofessional writers will surprise readers, the sharp observations and lyrical language from Americans from all walks of life—the bookseller who was aboard the Lusitania, the taxi driver serving in a Mobile Ordnance Repair Shop who corresponded with his sister, nurses’ diaries, the schoolteacher’s comments on the riots in East St. Louis, the Ivy Leaguers who flew with the Lafayette Escadrille, the soldier from Independence, Missouri, writing home to his sweetheart before returning to start his career as a haberdasher and later in politics. . .

World War I and America is part of a larger two-year initiative, supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, that is designed to bring veterans and the general public together to explore World War I’s continuing relevance one hundred years later. Visit ww1america.org for more information on the project, including a calendar of free public programs around the country, videos, and other resources for teachers and readers.