By Wendy Lesser

Contrasting two very different films inspired by Kenneth Fearing’s classic suspense novel, Wendy Lesser argues that the less faithful version is the more satisfying movie.

We tend to imagine that faithfulness to the source is the essential quality of an adaptation. But sometimes violent change works better than minimal tinkering. That’s the case with Kenneth Fearing’s novel The Big Clock, which has twice been adapted to the movies—once under its own name, in 1948 (a mere two years after the book’s publication), and once in 1987, under the title No Way Out.

The book is a noir classic. Not just a thriller writer, Fearing composed poetry that’s been collected in the Library of America (Kenneth Fearing: Selected Poems, edited by Robert Polito), contributed journalism to The New Yorker, and cofounded Partisan Review. But he never really topped this singular achievement. The brief, fast-paced novel is recounted by a number of different narrators (somewhat in the manner of that earliest of thrillers, Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White), but chief among them is the book’s hero, or at any rate protagonist, George Stroud. Stroud works for a magazine corporation that closely resembles Time, Inc. His overall boss is the ruthless Earl Janoth, who has a gorgeous, icy, blond mistress named Pauline. The plot thickens when Stroud, unbeknownst to Janoth, also becomes involved with Pauline, and it thickens even further when Stroud witnesses Janoth going into Pauline’s building on the night she is murdered. The crux of the plot, and what makes it a great thriller, is that the guilty, terrified Janoth and his amoral henchman, Steve Hagen, then select their clever employee George Stroud as the man to locate this unknown witness. Janoth’s and Hagen’s plan (of which Stroud becomes all too aware) is to eliminate the witness while blaming him for the murder. So Stroud’s task is to employ the full force of the magazine empire to find this person—himself—at the same time as he slows up the works sufficiently to prove Janoth’s guilt instead. The “big clock” of the title thus alludes simultaneously to the empire of Time magazine, the time-serving grind of corporate life in general, and the count-down clock against which Stroud is feverishly working on two different fronts.

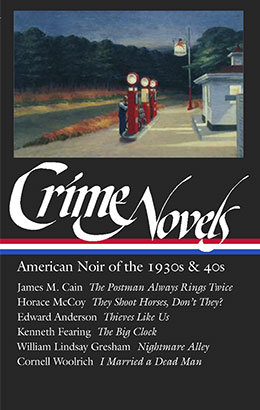

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s & 40s |

As with many noir heroes, both filmic and novelistic, George Stroud is not a hundred percent nice guy. Nicholas Christopher, who introduced the NYRB Classic edition in 2006, became so exercised about Stroud’s flaws that he failed to find anything at all redeeming in him. Among the insults Christopher hurled at Fearing’s main character—some of them glancingly hitting the author as well—were “serial adulterer,” “drunk,” “a corporate man,” “empty,” “numbed,” “stale,” “cold and shallow,” and “plagued by irritation, not angst.” (And that’s just from page one of the introduction.) What such characterizations seem to miss is that George Stroud is essentially our stand-in in this story, and however imperfect he is, we are pretty much rooting for him to win. This is not only because he is clever, observant, and unfairly victimized, but also because he is companionably witty and has unusually good taste. His taste comes out in the fact that he collects the paintings of an artist named Louise Patterson, a figure whose work turns out to be an important element in the plot.

Enter the 1948 filmmakers, including the director John Farrow and the screenplay adapter, Jonathan Latimer. They preserve all the externals of the book—the title, the magazine setting, the characters’ positions and names, even the Louise Patterson paintings—but they proceed to soften the Stroud character, seriously diminishing the noir character of the whole enterprise. Instead of casting a complex figure like Robert Mitchum or Joseph Cotten in the role, they seize on the bland Ray Milland, a suitable everyman. Stroud’s long-term affair becomes a single date, so he is no longer a “serial adulterer” and is instead deeply attached to his beautiful wife (played by the director’s own wife, Maureen O’Sullivan). The murderous Earl Janoth gets portrayed in fine if exaggerated style by Charles Laughton, but the even more important villain, Steve Hagen, gets reduced to a near-nonentity when rendered by a gray-tinged George Macready. In the end, the only scenes that work as vibrantly as they did in the book are those featuring Elsa Lanchester (erstwhile Bride of Frankenstein) as the eccentric artist Louise Patterson: her quick-witted refusal to recognize the missing witness in the person of George Stroud is what saves him from being apprehended. Visually, the movie does have its occasional good moments—filmed in black and white, it makes use of its Art Deco corporate and New York scenery to great effect—but on the whole it completely lacks the edge of a real thriller.

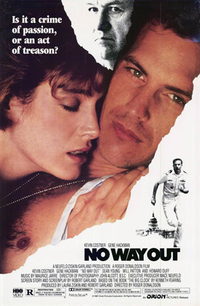

When it came time to make the 1987 No Way Out, director Roger Donaldson and screenwriter Robert Garland went back to the drawing board, junking just about everything from the Fearing book except its central premise—that the only man who could potentially testify against his powerful boss in the murder of their joint lover is precisely the person assigned to find that mysterious witness.

All the names have been changed. George Stroud is now Tom Farrell, and he has no wife at all, so he can’t be an adulterer of any kind. (In fact, he is a completely unblemished Navy hero: we even see him rescuing a fellow sailor at sea.) Earl Janoth, the corporate magazine owner, has become David Brice, Secretary of the Navy, and his assistant is Scott Pritchard, not Steve Hagen. The blond Pauline has become a brunette Susan, and even the movie itself has changed its name, borrowing its title from Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1950 noir, which had nothing at all to do with the Fearing novel.

What this switch to the Washington political setting does is to cause all the plot elements to be made up afresh, with excellent results. In keeping with the 1980s aura of growing paranoia about the government, there is a background story involving scary senatorial and C.I.A. figures who are working against the comparatively benign Brice to influence Defense Department policy. Tom Farrell is brought in to provide “intelligence” to Brice and Pritchard about what these scum might be up to, and when Tom meets the flamboyantly sexy Susan at a party, he apparently has no idea she is involved with his boss, though she eventually reveals who her sugar-daddy is. (“You know I work for Brice?” Tom says, horror-stricken. “That makes two of us,” Susan answers.) The murder becomes an accident—Brice, driven into a jealous rage over the unknown other man, mistakenly pushes Susan off a second-floor interior balcony, and she dies when she crashes through a glass table. To cope with and contain this fact, a penitent Brice and a sinister Pritchard decide that their key snoop should now be reassigned to find the elusive “Yuri,” a rumored Russian spy in whose existence they don’t really believe but who can cover for their unknown witness. From there the plot proceeds very much as in the novel, with Tom racing to find evidence against David Brice even as he is forced to mastermind a full Defense Department search that will ultimately, if it is successful, point toward him.

Lots of delightful gimmicks—a jewelry box with Moroccan writing that Brice gave to Susan, a Polaroid negative from a picture she took of Tom, DNA from semen, phone numbers to and from Susan’s phone, credit card receipts and witnesses from a weekend jaunt the two young lovers took, all intermingled with computer technology galore—enter the story and periodically raise the chances of one outcome or another. Tom’s only completely trustworthy ally, a computer geek who is confined to a wheelchair (and is thus, in movie terms, signaled to be both “good” and “at risk”), gets coldbloodedly shot by Pritchard; two goons from Special Forces roam the Pentagon halls and the larger city attempting to kill off people who get in Pritchard’s way; and, just as in the book, a final showdown at our hero’s place of work involves his having to hide in various obscure locations as witnesses are paraded through the building. It is all extremely well done: inventive, thrilling, and continually surprising, up to and including the shocking denouement about Tom, which reveals another layer to his character that practically recasts the whole plot.

No Way Out has a brilliant script, excellent directing, and even a fine musical score (by Maurice Jarre), but what really lifts it to the level of a great thriller is the casting (Ilene Starger was the casting director). Actors I have hated elsewhere—Kevin Costner, who plays the central character, and Sean Young, who takes the role of his lover Susan—are here actually used for their bad points. Costner’s Marlboro-Man woodenness (as exemplified in the 1987 Untouchables) functions perfectly for the emotional concealment his intelligence job constantly requires of him, and the fact that he seems stupider than he could possibly be also contributes to the veracity of his hero-turned-sleuth role. Sean Young’s brassy near-hysteria (her only response to either pleasure or disgust is a forced-sounding giggle) makes sense in a hardboiled mistress-for-hire. This actress’s inability to deliver any line of dialogue as if she really means it is exactly what we might expect from her compromised situation, and rather than making us question her performance the way it usually does, here her patently bad acting heightens our anxiety about whether Tom can trust anyone, including Susan.

But the true acting in No Way Out is carried off by Gene Hackman as David Brice and, above all, by Will Patton as Scott Pritchard. The grotesquely powerful and narcissistically stupid Earl Janoth of the Fearing novel (“He wasn’t adjusting himself to the big clock. He didn’t even know there was a big clock”) becomes, in the person of Hackman’s Brice, a figure we can actually feel some sympathy for. He is not a bad guy, but a person who has made bad mistakes—some of them fatal, but for reasons that are no more worthy of condemnation than those made by his employee Tom Farrell. (They both, for instance, get too involved with the wrong woman, though with completely different motives.) Hackman’s slightly ugly, surprisingly expressive, immensely intelligent face—the same face he wore in The Conversation a dozen years earlier, in a role that will live forever—insures that we don’t fully want Tom to expose him, though we realize that’s the only way out for our hero. What the Hackman/Costner pairing does is to make us feel divided in much the way that George Stroud’s complex character did in the book.

The triumph of the movie, though, lies in Will Patton’s portrayal of the big boss’s henchman. In its own peculiar way, it goes straight back to the Fearing novel. “Hagen was a hard, dark little man whose soul had been hit by lightning, which he’d liked,” Stroud tells us in his narration. “His mother was a bank vault, and his father an International Business Machine. I knew he was almost as loyal to Janoth as to himself.” Will Patton is neither hard nor dark (if anything, he’s strangely and scarily soft), but that phrase “which he’d liked” utterly characterizes the chilling performance he gives here. There is something terrifying behind his bland smile, and we feel it the first time we see him onscreen, when he says of his boss, “I’d die for him.” That turns out to be true, and there is a sense in which his despicable ruthlessness has its admirable side, in that it’s all devoted to Brice.

The fact that Pritchard is revealed to be a homosexual (in a brief aside between some Defense Department jerks) also refers back to the novel, where Earl’s and Pauline’s fatal argument stems from the fact that she has accused Janoth and Hagen of being secret lovers—a plot element notably omitted in the 1948 film. We do not feel, in No Way Out, that Brice and Pritchard are sexually involved with each other. But there is some way in which Patton’s subtle, frightening portrayal, suggesting as it does both the film’s secret loyalty to its literary source and Pritchard’s demonstrable loyalty to the boss he loves, harks directly back to Fearing’s original noir atmosphere. In doing so, it seems to counteract all the Hollywood cleaning-up that took place in the interim between the 1946 novel and the 1987 film.

Video: 1987 trailer for No Way Out

The Big Clock (1948). Directed by John Farrow. Screenplay by Jonathan Latimer, from the novel by Kenneth Fearing. With Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, and Elsa Lanchester.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Fandango

No Way Out (1987). Directed by Roger Donaldson. Screenplay by Robert Garland. With Kevin Costner, Gene Hackman, Sean Young, Will Patton, George Dzundza, Iman, and Fred Dalton Thompson.

Buy the DVD • Buy the Blu-ray • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Wendy Lesser is the editor of The Threepenny Review and the author of eleven books. The latest, You Say to Brick: A Life of Louis Kahn, has just been published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.