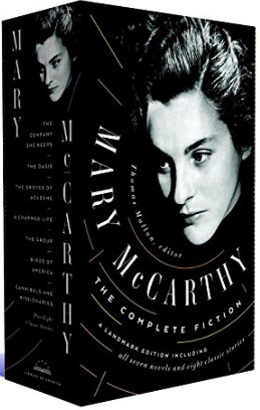

A major modern writer enters the Library of America series this month with the publication of Mary McCarthy: The Complete Fiction. Collecting seven novels and eight short stories, this two-volume set captures the full scope of the author who depicted the lives of twentieth-century American women with a hitherto unprecedented candor and intellectual fearlessness.

Thomas Mallon, who edited both volumes, is the author of nine novels, among them Watergate, Finale, and Fellow Travelers, and seven books of nonfiction. He writes regularly for The New Yorker and The New York Times Book Review.

Mallon was also a protégé and friend of McCarthy’s, as he recounts in the following email interview.

LOA: Readers discovering Mary McCarthy’s fiction in 2017 will likely be struck by her formidable intelligence and, possibly, by her refusal to ingratiate herself with the reader. In contemporary terms: she doesn’t seem all that interested in being likeable. Thoughts on this?

Mallon: Yes—what a relief to hear such a voice! McCarthy’s whole psychology and belief system were completely apart from our current culture of please-love-and-understand-me victimization. She once wrote that her life had been a continual “conflict between excited scruples and inertia of will,” and she was more aware of her moral failures than her successes. “Not favorable” was the answer she gave when asked to render an overall judgment of herself.

LOA: McCarthy’s penchant for using real people and events as the basis for her fiction was much remarked on in her day. How important is that knowledge/awareness to the reading experience and reading pleasure of a reader today?

Mallon: I honestly don’t think it matters much—which is testimony to the sharpness and vitality of the fictionalized characters on the page. If you know that Miles Murphy has a basis in Edmund Wilson (or Macdougal Macdermott in Dwight Macdonald) you may experience a roman à clef pleasure, but that will only add to the more fundamental enjoyment you’re experiencing from McCarthy’s artistry.

LOA: In 1941, “The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt” (one of the interlinked stories in McCarthy’s first book, The Company She Keeps) made waves for its sexual candor and the boldness of its female protagonist. Alison Lurie and Pauline Kael later testified how important it was for them as young women in the 1940s. Alfred Kazin, on the other hand, saw in it “contempt for men.” How does it read now?

Mallon: In a letter to me, Mary once included Kazin among those critics who had “elected me as their field to trample over.” I don’t find any contempt for men in McCarthy’s treatment of sex. What one sees is an awareness of how ensnaring and comical and revealing sex can be. I’m not the first to point out that it is impossible for a reader to be aroused, except intellectually, by any sex scene McCarthy ever wrote. She is fully aware of sex’s power, but she never rhapsodizes it. By not doing so she gives readers, both men and women, a certain power over sex. Or at least a new perspective on it.

LOA: The Group became a major best seller in 1963, after McCarthy had worked on it for roughly a decade. Why did it strike such a chord—was it a case of the right novel arriving at the right time?

Mallon: The public was ready for a new candor. Sexual mores were changing, along with the apparatus of sex (the pill). And the last serious restraints of legal literary censorship had more or less disappeared. The book is full of the maverick moral tendencies I mentioned in the answer to your first question. In the novel McCarthy takes a less admiring view of her own generation of Vassar girls than she does of their mothers and teachers.

LOA: Contemporary novelists like Hilary Mantel and A.S. Byatt have LOA: McCarthy’s last two novels, Birds of America (1971) and Cannibals and Missionaries (1979), express an increasing disillusionment about the ability of artists and writers to effect change in the world—a noteworthy development coming from this lifelong politically engaged intellectual. Is there a connection to her years spent opposing America’s war in Vietnam?

Mallon: Vietnam was an urgent, years-long preoccupation of hers, and it had a significant effect on her fiction. Eight years—a long time to go between novels—went by between The Group and Birds of America. During that time Mary wrote extensively about the war and made two trips to Vietnam, one to the South and one to the North. The easiest thing for her to do would have been to stay home in Paris and capitalize on the success of The Group by writing another book in a similar vein as quickly as she could. But, no doubt to the exasperation of her publisher, she thought much less in career terms than most writers do. She responded to her own intellectual passions, which, at her own speed, found their way into those last two novels. Birds of America is filled with meditations on the war, equality, and the threats to nature (human and otherwise) from a culture that is ever more flimsy, mechanical, and mass-produced; it’s almost what the French call a conte philosophique. Many of the same issues also come into play with Cannibals and Missionaries, but that last novel, along with its play of ideas, is also driven by a cracking good plot involving a hijacked airplane.

LOA: You’re the rare Library of America editor who not only knew the author in question personally but also maintained a longstanding friendship with her. Tell us a little about how you came to know McCarthy, and what her work has meant to you over the years. Do you have a favorite McCarthy anecdote?

Mallon: The first book of Mary’s that I read, in the summer of 1971, was the just-published Birds of America. The subject matter seemed a perfect fit: like its protagonist I was nineteen, and I was about to go to Europe for the first time. I developed an immediate avidity for all her work in so many different genres: fiction, criticism, travel writing, political polemic. Her book of essays, On the Contrary: Articles of Belief, 1946-1961 is, I think, the book that made me want to be a writer. In the fall of 1972, I was a senior at Brown University and wrote my English department honors thesis on her work. I think we were supposed to turn in about fifty pages; mine was 152. My advisor insisted I send it to her; I did, and she wrote back, at considerable length—a letter that was complimentary, corrective (she didn’t hesitate to tell me where she thought I’d interpreted something wrong), and encouraging: she concluded it by asking if I was thinking about becoming a writer. I damn near fainted.

A favorite anecdote? Perhaps from the summer of 1982, when I was up in Castine, Maine, staying with Mary and her husband Jim West. This was at the time Mary was doing legal battle with Lillian Hellman, who had sued Mary for saying, on television—and quite justly—that “every word [Hellman] writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.’” Well, we went off to a cocktail party in Castine, and one of the guests had just come from Cape Cod. (Hellman lived on Martha’s Vineyard in the summers.) Somebody asked the man what the weather had been like on the Cape, and he replied that it had been awful. I remember Mary smiling and saying, quietly and to no one in particular, “I’m glad.”

After Hellman’s death, which occurred before the case could be decided in court, Mary declared that there was no pleasure to be taken from the sudden demise of enemies: “You have to beat them!”

Mary McCarthy’s piece “Hanoi—March 1968” is included in the Library of America volume Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959–1969.