By Armond White

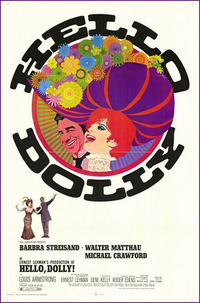

Gene Kelly, Barbra Streisand, and Louis Armstrong fulfill Thornton Wilder’s aesthetic foresight in one of the last big-budget Hollywood musicals.

The exclamation point in Hello, Dolly!’s title expresses more than mere enthusiasm. It heralds the last of the big-budget Hollywood musicals in which the studios routinely repeated the box-office formula of such Sixties blockbusters as West Side Story, Mary Poppins, and The Sound of Music. It’s part of the film culture I grew up with, enjoying Hollywood flash alongside the aesthetic thrill of European art cinema. But the end of an era can also bring about its refinement and I always found Hello, Dolly! to be the best movie of its kind: Its sheer kinetic Color by DeLuxe excitement outdoes any movie-musical since the genre’s Thirties, Forties, and Fifties apex. The huge and overweening spectacle has a glossy polish that director Gene Kelly brought from his MGM glory days to this Twentieth Century-Fox 70mm epic. And though Kelly’s infectious grin never appears on Hello, Dolly!’s wide screen, you can feel his impetuous personal energy and charm—so reminiscent of his rambunctious, widely recognized classic Singin’ in the Rain and his rollicking-philosophical It’s Always Fair Weather. The film’s expansive scale and dynamism are amazing to behold and not just as production values: they also fulfill the complex aesthetic intentions of playwright Thornton Wilder, whose 1955 The Matchmaker was Hello, Dolly!’s source material. True to Wilder’s original story of “a day well spent,” Hello, Dolly! depicts the widow Dolly Gallagher Levi leading a group of young lovers from suburban Yonkers, N.Y., to New York City where she works out her design to marry the small-town merchant Horace Vandergelder. This plot (which Wilder first titled The Merchant of Yonkers and designated “a farce in four acts”) draws together three pairs of lovers with such comic precision that we enjoy the story’s simple clarity.

That exclamation point also defines Hello, Dolly! as, specifically, a blockbuster ritual, shamelessly catering to the public’s awareness of the show’s unabashed, irresistible aim to please. The film’s December 1969 release came long after the show had won enormous popular favor. There had been a fondly remembered film version of The Matchmaker, directed by Joseph Anthony in 1958, that starred Shirley Booth, Anthony Perkins, Shirley MacLaine, and Paul Ford. Those who had never seen either the original Carol Channing Broadway production of the musical, or its road-show spinoffs starring such Hollywood luminaries as Ginger Rogers, Betty Grable, Eve Arden, and Dorothy Lamour making personal career comebacks, still knew its plot from cultural osmosis. And Louis Armstrong’s rapturous 1964 hit recording of the title song brought the show’s musical delight to the world. Critics who panned Hello, Dolly! as “old-fashioned” didn’t realize how Kelly’s screen adaptation connected to the times. He visually and viscerally inflated the pleasant-enough plot. His soundstage and outdoor performance spaces were set to fulfill Wilder’s modernist ideas.

| Read The Matchmaker |

|

| in Thornton Wilder: Collected Plays and Writings on Theater |

In dramatic texts, novels, and published prefaces, Wilder had articulated the most sophisticated appreciation of theater as cultural ritual that exists in American literature. How Kelly put that sophistication on screen, with visionary enthusiasm and ingenuity, was virtually predicted in Wilder’s “Preface to Our Town” when he described the plays of his theatrical heritage: “The art is so consummate that the secret is hidden; peer at them as hard as one may; shake them; take them apart; one cannot see how it is done.” The master craftsmen responsible for Hello, Dolly!’s visual astonishment hide their secrets within the splendor of their achievement. Despite being a mainstream blockbuster (its $20 million cost was touted on the cover of Life magazine) the film never feels impersonal. Auteur Kelly invests his passion for movie musicals as fully as he did in his vigorous collaboration with Vincente Minnelli on An American in Paris. The robust choreography of Michael Kidd (Seven Brides for Seven Brothers), which intensifies the famous “Waiters’ Gavotte” dance contest into a delirious deconstruction of working-class labor as synchronized choreography, becomes a crucial part of Hello, Dolly!’s fun as meta-cinema and filmed-theater extraordinaire—what Pauline Kael described as the team’s “giant-stage concept.”

When the ensemble number “Put On Your Sunday Clothes” carries Barbra Streisand’s Dolly and ensemble en route to New York, Kelly and Kidd dare portray their spiffing-up and traveling by referencing the middle-class family ceremony in Minnelli’s Americana masterpiece, Meet Me in St. Louis. At the Yonkers train station, where the song reaches its peak, they evoke the infectious “Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe” number that highlighted George Sidney’s The Harvey Girls. This is total movie modernism—a reverence for Hollywood history in the manner of Wilder’s “Preface” (“The spectator through lending his imagination to the action restages it inside his own head.”) For me, these homages felt as au courant as the French New Wave. Kelly’s cinematic giant stage is consonant with the outsize way Jacques Demy paid homage to Hollywood musicals in Lola, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and The Young Girls of Rochefort. Hello, Dolly!’s formal complexity barely conceals Kelly’s expertise and Wilder’s imagination. This highly anticipated blockbuster boasted of its own form—virtually begging for appreciation, a very modernist thing to do—then delivered on spectacle and emotion.

Yes, cinematographer Harry Stradling’s deep-focus exteriors put the money on screen, but dig the old pro’s modernist trick of extending perspective past the giant sets and manicured fields toward infinity, to look beyond Yonkers or bustling New York City to the ends of the earth. Stradling turns Wilder’s theory in the Our Town preface—“the stage cries aloud its mission to represent the Act in Eternity”—into photographic reality. In Hello, Dolly!, movie-musical artifice must be understood as a stylized vision of experience. Whenever Hello, Dolly! looks old-fashioned (the “Elegance” number recreating “A Couple of Swells” from Charles Walters’ Easter Parade) is precisely when its stylization is working as modernist self-awareness. Kelly, who performed the role of expatriate American muse in Demy’s Nouvelle Vague experiment The Young Girls of Rochefort, is once again extending the MGM legacy.

Against the late-Sixties trends of “realism” and “cinema verite,” Hello, Dolly!’s spectacle stays faithful to Wilder’s hypothesis that “theater longs to represent the symbol of things, not the things themselves.” This also fits the Nouvelle Vague practice of revising traditional genres (the romantic farce, the movie-musical) by embracing what was once considered naive with affectionate knowingness. Casting twenty-seven-year-old Streisand as middle-aged widow Dolly especially helps to invigorate this conceit. Her youthful energy, singing talent, and comic timing (the Mae West inflections on “So Long, Dearie” are the film’s only instances of camp) stay faithful to the play’s farcical examination of romance. “One way to shake off the nonsense of the nineteenth-century staging is to make fun of it,” Wilder wrote. “This play parodies the stock-company plays that I used to see . . . when I was a boy. . . . My play is about the aspirations of the young (and not only of the young) for a fuller, freer participation in life.” That scholarly reflection describes the essence of many American musicals. Kelly stages Hello, Dolly! so that Wilder the aesthetic theorist meets his own future.

Entertaining though Wilder always is, his works are not mere entertainments. Scholar James V. Schall posited Wilder’s concern with “providence and the meaning of each human life.” In his stage dramas, the mix of authorial invention and cosmic destiny play out across Time but also in real performance time—Wilder at his most avant-garde insists that we notice both. Having pop star Streisand in this role, imbuing it with all the associations of her renowned revisions of American Songbook standards, helps sustain a happy suspension of disbelief. In Streisand’s performance, Dolly Gallagher Levi is a poor player that struts and frets her hour upon the stage; she demonstrates that the playful can also be a source of the profound.

After studies at Yale, Wilder traveled in Europe where he discovered the plays of Luigi Pirandello which he praised as “Philosophical farces, actually,—strange contorted domestic situations illustrating some metaphysical proposition.” Wilder himself sought to create “art that did lead out of the abyss of despair.” If Hello Dolly!’s source play, The Matchmaker, is a lesser work than Our Town, it’s largely because it avoids the pang of death and, instead, uses farce to portray romantic longing. This time, the desire for love becomes not a trenchant, existential cry, but the fuel for folksy charm and comic stylings (and in Hello, Dolly!, Jerry Herman’s rousing, unpretentious songs). Still, Wilder’s characters are homey but not exactly homespun. They spin out from his sensitivity to the complexities of romance—and, indeed, of human consciousness.

In Hello, Dolly! the 1880s setting encapsulates the play’s own nostalgia for vanishing ways of living and of Americans fulfilling their potential. Savoring the period details as they unfold is like watching a snow globe in summer. It allows us to examine how life used to be so that we can contemplate what has changed or not changed in our present-day experience. This process looks mundane in Anthony’s conventional direction of The Matchmaker but it becomes an inescapable marvel when Kelly, through movement and magnitude, transforms Wilder’s theories into kinetic spectacle.

Anthony and Kelly both began their careers as performers before becoming film directors. Anthony appeared in The Shadow of the Thin Man and was a dancing partner for Agnes de Mille. Kelly’s performing career from Broadway to Hollywood is legendary. They shared an expertise about performance and its presentation. Both seem satisfied that Wilder’s simple yet studied story (an expansion of a one-act 1835 British farce by John Oxenford titled A Day Well Spent) wasn’t solely a diversion. Even in The Matchmaker, the modernist architect of Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth permitted characters to break the fourth wall. Vandergelder directly addresses the audience in a philosophical aside, and, in fact, each major character steps forward with his or her own personal confession.

Dancer-director Anthony only occasionally uses that modernist device, but when he does, he works to give the on-screen characterizations greater intimacy—Shirley Booth’s Dolly and Anthony Perkins’s anxious bachelor Cornelius Hackl address the camera and break the audience’s hearts, particularly through their distinct vocal timbre. Booth overflows with matronly kindliness (her sing-song litany boosting Cornelius Hackl’s reputation is both cunning and irresistibly sweet) and Perkins gives off boyish goodness (there’s gee-whiz exuberance in his hormonal excitement). Anthony’s on-screen stagecraft puts quote marks around everything, illuminating The Matchmaker’s Kindness and Goodness in a manner much like Jacques Demy getting to the essence of romantic will in Lola, letting Dolly and Cornelius’ personal qualities resolve Wilder’s overeducated perplexity about Life and Love.

Anthony’s film quaintly formalizes The Matchmaker; it’s a delightful, humble achievement. Kelly’s film of Hello, Dolly! is in crucial ways the opposite: Big, circusy, completely contrived—a sincere Wilder adaptation that also answers his call for sophisticated artifice. Look at the shifts between small detail and large vistas in the opening New York street dances where close-ups of feet walking, hopping, and skipping rhythmically lead to the first close-up of Streisand’s Dolly standing atop a double-decker bus with the city’s panorama behind her. This brief instant of Streisand’s Dolly flirting with the camera is one of the times Kelly, too, breaks the fourth wall. Though it happens less in Dolly! than in The Matchmaker, dancer-director Kelly shows consistent theatrical-cinematic artfulness.

Note the zoom shot of Cornelius (Michael Crawford) and his sidekick Barnaby (Danny Lockin) approaching Irene Molloy’s (Marianne McAndrew) hat shop; the strikingly abrupt shift in focus, a stylistic deviation, gives way to conventional farce staging in the millinery scene’s mix-up between the lovers—Cornelius and Irene—and Vandergelder (Walter Matthau). The movie goes from stagey to cinematic and back—without clashing visually. That balancing act continues in such giant-stage spectacles as the Yonkers train station, the Hudson Bay wedding landscape, the Union Square street set used for the “Before the Parade Passes By” showstopper, and the closing wedding procession at a nondenominational chapel with white clapboard front, colonial columns, and towering spire. Working in these artificial-mixed-with-real settings, Kelly’s craft goes to the heart of Wilder’s aesthetic.

The film’s defining moment is also its highlight: Streisand and Louis Armstrong performing at the title song’s climax. True to Wilder’s understanding of theater and its sociological, existential nature, their duet connects the traditional Broadway show to its status as a cultural phenomenon. Recall Armstrong’s Number 1-selling recording as a fact of modern life and the old-fashioned farce of Hello, Dolly! suddenly becomes Pop Art. That harmonic interchange between Streisand and Armstrong—Jewish-American pop corresponding with African-American jazz—elevates Hello, Dolly! above romantic farce to a celebratory representation of ethnic and class communion. It vivifies the film’s social moment.

Nothing else in the history of movie musicals can beat it. This intercommunication is what Wilder’s theater theory and Hollywood populism are all about. A grateful viewer can only exclaim: Encore!

Video: Original 1969 trailer for Hello, Dolly! (4:13)

Hello, Dolly! (1969). Directed by Gene Kelly. Screenplay by Ernest Lehman from the Broadway musical by Jerry Herman and Michael Stewart (based on Thornton Wilder’s The Matchmaker). With Barbra Streisand, Walter Matthau, Michael Crawford, Marianne McAndrew, Louis Armstrong, E.J. Peaker, and Danny Lockin.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

The Matchmaker (1958). Directed by Joseph Anthony. Screenplay by John Michael Hayes (based on Thornton Wilder’s The Matchmaker). With Shirley Booth, Anthony Perkins, Shirley MacLaine, Paul Ford, Robert Morse, and Perry Wilson.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Armond White is Film Critic for National Review and Out Magazine. He is author of The Resistance: Ten Years of Pop Culture That Shook the World, Keep Moving: The Michael Jackson Chronicles, New Position: The Prince Chronicles, and Rebel for the Hell of It: The Life of Tupac Shakur.

The Moviegoer, a biweekly feature from Library of America, showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.