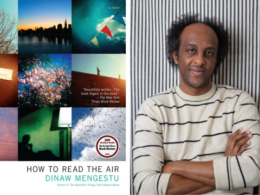

Our series of guest contributions by contemporary writers continues today with the following piece by Sarah Manguso, whose new book 300 Arguments has just been published by Graywolf Press.

300 Arguments is a series of aphorisms that at first appear unconnected but subtly describe a quasi-narrative that can be taken, in the words of admirer John Jeremiah Sullivan, as “a sort of novel.” The book has already won praise from NPR and the Portland Mercury, which saluted its “difficult-to-deny power.”

Below, Manguso acknowledges some of the disparate influences on her genre-defying work.

These books each taught me something about constraint, and their lessons remained with me as I wrote 300 Arguments.

H. D. Thoreau, Walden. If we leave aside, for a moment, the disappointment of knowing that Thoreau’s mother brought him lunch every day, _Walden demonstrates that you can at least make a pretense of leaving the whole human world aside and taking what’s left, a person in a wilderness, as your subject, as long as you, the writer and the subject, believe the pretense.

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. In a recent interview, Dillard said that when she was attempting to sell this book, “I was no one. I was less than no one. I was a woman, a housewife, in the South.” She wrote in first-person but left woman, housewife, and the South out of the book almost completely. What she included in the book was a world more vivid than the one I inhabit at this very moment, sitting and staring into a computer screen. From this book I learned that you can include or exclude anything you want.

Joe Brainard, I Remember. I Remember proves that you can use a minor form for a magnum opus; that a light touch can leave a deep impression; that you can use what you notice as the point of origin and get a piece of writing to go almost anywhere; but, on the other hand, that linked association between details must be used with exquisite care for fear of losing a reader in a haphazard muddle.

William Maxwell, novels and stories. Maxwell lost his mother when he was young, and he never stopped writing about it. In almost all of his stories, somewhere, someone’s mother is inaccessible. Maxwell taught me that you don’t have to stop writing about the one thing you’ll never get over. You can put it in every book you write, and it just keeps on being the most important thing, just as it is in your actual life. If it’s still urgent to you, you can keep writing about the same thing forever.

David Markson, Reader’s Block and its three sequels. From these four books I learned that you can make your failure to write the book the subject of the book.

Sarah Manguso’s essays have appeared in Harper’s, McSweeney’s, the Paris Review, the New York Review of Books, and the New York Times Magazine. She has published seven books, among them three memoirs, Ongoingness, The Guardians, and The Two Kinds of Decay; a collection of short stories; and two poetry collections. She currently lives in Los Angeles and is the Mary Routt Chair of Creative Writing at Scripps College.