By Farran Smith Nehme

Location shooting, unvarnished textures, and a disdain for euphemism make this adaptation of William Faulkner’s 1948 whodunit the most successful of Hollywood’s postwar race-themed films—one that earned the respect of even Ralph Ellison.

The word lands just minutes into Intruder in the Dust, the 1949 adaptation of William Faulkner’s novel, directed by Clarence Brown. A youngish white man, tired of waiting to get his shoes shined outside a small-town Southern barbershop, walks in and demands to know where “the shine boy” is at. Come to think of it, he’s seen no black folks at all in twenty-four hours. That’s because there’s trouble afoot, he’s told. Vinson Gowrie, son of a low-rent, troublemaking clan that dominates a whole corner of the county, has been killed.

“Shot in the back,” adds a skinny, laconic patron, “by a n——.” Within minutes, a siren sounds, and the barbershop denizens all come running, grabbing wallets, coats, shoving a hat over a head still full of shampoo, eager to see the prelude to what will no doubt prove to be the biggest show in some time: a lynching.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in William Faulkner: Novels 1942–1954 |

Intruder in the Dust, published in 1948, has Faulkner’s trademark long sentences snaking across the page, as well as the digressions that often achieve the cadences of poetry. But Intruder is a brief book by Faulkner’s standards, and it hangs on an unusual whodunit plot. Charles “Chick” Mallison (played in the movie by The Yearling’s Claude Jarman) works to prove the innocence of Lucas Beauchamp (Juano Hernandez), a proud black landowner who’s accused of shooting a white man. Assisting Chick are the town’s oldest spinster, Miss Habersham (Elizabeth Patterson); his childhood friend, a black teenager named Aleck (Elzie Emanuel); and, with some reluctance, Chick’s Uncle John Stevens (top-billed David Brian), a lawyer who represents Lucas despite believing in his guilt.

There were three other earnest Hollywood attempts at tackling Jim Crow America in 1949: Pinky, Home of the Brave, and Lost Boundaries. Intruder in the Dust has aged the least. Its location filming, its unvarnished textures and sounds still feel uncannily accurate. Witness the willingness to invoke that atomic bomb of a slur. Aside from being condemned in Gentlemen’s Agreement, the word had been unheard in a major Hollywood film since The Emperor Jones in 1934, according to scholar Thomas Doherty. But it was common enough in mid-century Mississippi, even if nice folks weren’t supposed to utter it. “Why, Chick,” is his mother’s gasped rebuke when her son says of Lucas, “They’re gonna make a n—— out of him once in his life.” This is the rare studio movie that strives to avoid euphemism.

Ben Maddow’s screenplay follows the novel in nearly all the most important ways. The script observes the South’s intricate class divisions, making it clear that the town’s sheriff (Will Geer) is working to keep his prisoner safe not out of liberal nobility, but because he won’t let “a passel of Gowries” usurp his authority. Jettisoned are the things that would fail to transfer to film, such as Faulkner’s meditation on Pickett’s charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, now famous from Shelby Foote’s reading of it in Ken Burns’s The Civil War. Maddow retains Faulkner’s wry humor as well as some telling moments of physical business, like the sheriff cooking himself breakfast while he listens to evidence of Lucas’s innocence.

And Maddow recreates Faulkner’s characters in all their richness. As played by Jarman, whom Brown himself discovered in a Nashville classroom when casting The Yearling, Chick has an open, guileless face that suggests someone far more sensitive than an average son of white Southern privilege. Lucas once fished him out of a frozen creek, an act of decency that Chick tried to pay for; this was an insult he eventually came to regret. Chick’s encounters with Lucas give him a model of masculinity that is entirely unlike Chick’s own fussy, bourgeois father, who shrugs, “It’s happened before and it’s bound to happen to again” and is ready to leave it at that. Chick has a black counterpart in the smaller role of Aleck, played by Elzie Emanuel, who also has a gangly physique and transparent emotions. Alas, Brown mis-directed Emanuel to several eye-rolling, knock-kneed “comic” moments that were derided at the time in the African American press. When allowed to react naturally, he’s very effective. Patterson’s Miss Habersham is a grand creation; an elderly, childless woman, she has status in the community, but no power. The lack of power helps give her the empathy that makes her want to help Chick and Aleck investigate the murder. The status means that she can get away with it. She can even watch a lynch mob’s leader soak the floor with gasoline and light a match, and call his bluff.

Most indelible of all is Lucas. He owns the land he farms, ten acres in the middle of a plantation, passed down through his family after a bequest by the original slaveowner. Puerto Rican actor Juano Hernandez, in a magnificent performance, shows with every gesture how that landowner status affects Lucas’s bearing and manners. Hernandez gives Lucas a distinctive walk: legs apart, arms hanging straight, with a pronounced sway from side to side. It is the walk of a man who believes in his right to take up space. Numerous times Brown’s camera catches the white characters as they watch Lucas and seethe over what that walk implies. Indeed, Lucas’s everyday attire is better than what a Gowrie could scrounge up for church: a morning coat, a spotless hat, a gold toothpick.

When Uncle John and Chick visit Lucas in his jail cell, the sheriff has taken away the mattress. Lucas has laid down newspaper to ease the pressure of the bedsprings on his skin, and he is lying on his back with one shoe under his head, so composed he suggests royalty at rest. The shoe is high-quality, like everything else he wears or carries. The mystery of who killed Vinson Gowrie is solved in part due to Lucas’s unusual gun, an heirloom Colt .41 that he carries on Saturday, like “a white man,” notes an exasperated Uncle John.

Lucas measures his speech like his gait, unhurried and precise. Faulkner, who declined to write the script but offered the company advice on casting and local customs, deemed Hernandez’s natural voice too sonorously classical for a Mississippi native, and coached the actor on the accent. David Brian also possessed a good voice, but it’s used to different effect. Tasked with most of the movie’s speechifying, Lawyer Stevens’s talk breaks into scenes like a radio announcer. The two actors play their most memorable scenes together, as in a jailhouse exchange when a frustrated John snaps, “Has it occurred it to you that if you just said ‘mister’ to white people, and meant it, you might not be sitting here now?” Lucas responds, with scathing calm, “So I’m to commence now? I can start off by saying ‘mister’ to folks that drags me outta here and builds a fire under me?”

There are other strong hints that Brown and Maddow are, at times, actively undermining Lawyer Stevens’s didactic pronouncements. As he and Chick stroll home through the warm dark after seeing Lucas in the jailhouse, and encounter Mr. Lilley (played by R. X. Williams, probably a Mississippi local), who’s out watering his plants, Mr. Lilley and Uncle John exchange a few words about the brewing Gowrie lynch mob, and Lilley ends with the jocular farewell, “Tell ’em to holler if they needs any help.” Uncle John turns to Chick and, as though this thought follows quite naturally, remarks “See, he had nothing against Lucas.” Uncle John adds that Lilley would be one of the first to contribute to Lucas’s funeral, and winds up with, “Now the white folks are gonna take [Lucas] out and burn him, with no hard feelings on either side.”

The movie finds other, non-verbal ways to convey the dark irony of this passage from the novel. For one, nothing about Lilley, or indeed Southern tradition, explains why Uncle John would find the man likely to do anyone a good turn, let alone a black man’s hypothetical family (Lucas’s wife is dead). Then and now, Lilley looks to most rational people like a fat, grinning ghoul, and Chick’s expression indicates he’s not convinced. Just a few scenes later, as Chick, Aleck, and Miss Habersham drive a truck out to a remote cemetery to dig up Vinson Gowrie’s body, Brown cuts several times to black tenant families tucking their children into bed, glancing fearfully at the headlights, and cringing at the sound of wheels on a dirt road. That light and those sounds mean one thing only, and the feelings about it are very hard indeed.

Clarence Brown read Intruder in the Dust in galleys. As a young man he’d witnessed the Atlanta race riot of 1906, and he said, “This was a picture I had to make.” One roadblock was Louis B. Mayer, still in charge of MGM, and as always not a man receptive to political filmmaking. And political this story certainly was; years later, it’s still hard to believe that Andy Hardy’s studio made it. It helped that Brown had been a top director at the studio for more than twenty years and considered Mayer a friend. Eventually, the boss relented after the project got the firm backing of MGM’s head of production, Dore Schary, “even though,” wrote Scott Eyman, Mayer “would undoubtedly have had a stroke if John Huston had tried to make it.”

Another question was where to film. MGM had the biggest and most spectacular backlot in the business, one that had subbed for everything from the streets of Laredo to the gardens of Versailles, and they didn’t see what was so goldurn special about Oxford, Mississippi. Brown, born in Massachusetts but raised in Tennessee, knew different. Shooting on location was—aside from casting Hernandez—his most vital decision. The town square is dusty, vast, and real. The people evoke Walker Evans, not central casting. And then there may have been whatever intangibles resulted from experiencing southern-style segregation up close. White company members enjoyed the hospitality of the University of Mississippi. Hernandez was housed separately at the home of a black undertaker. The cast and crew, wrote film historian Thomas Cripps in Making Movies Black, “were so careful not to violate racial etiquette that the locals gave them a farewell fish fry.”

Meanwhile, the real 1949 Oxford was going on screen, forever, as in the sequence that begins with a high-placed loudspeaker blaring the old Charleston dance tune, “Runnin’ Wild.” In several long, linked tracking shots, Brown and cinematographer Robert Surtees sink down to ground level, to a bus with its horn blaring as a bunch of eager young men tumble out. The camera glides past a little girl waving a mechanical flag, past other kids eating ice cream, a woman re-applying her lipstick in a side mirror, a card game, a kid with a yoyo. Finally Brown and Surtees light on a middle-aged woman carrying a baby, as she strides purposefully toward what turns out to be the car of Nub Gowrie (Charles Kemper), the murder victim’s brother. “Well, Mr. Gowrie,” she says, “when you reckon you gonna get started?” Gowrie climbs out of the car, and in another track, carries a gas canister to a nearby filling station, where a man in a suit fills it to the brim. The sloshing gas forms a wet track as Gowrie carries the can across the square. There is not a single black face in any part of this scene.

The truly chilling thing is that it’s possible—likely, even—that some of those faces in the crowd had real-life experience with what Brown was asking them to fake. In 1935, a twenty-eight-year-old black man named Ellwood Higginbotham was dragged from the Oxford jail and hanged by a mob of about 150, while a jury was still deliberating in his trial on a charge of killing a white farmer.

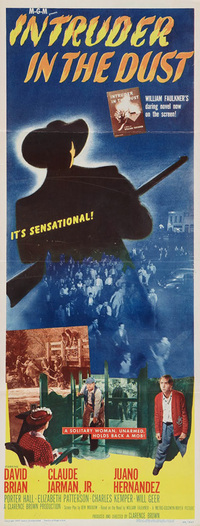

Intruder in the Dust had its premiere at the Oxford Lyric Theater on October 10, 1949. The budget had been top-drawer, the notices were stellar, but as Mayer had predicted, it was a box-office dud. People were tired of social problems, said the conventional wisdom; lack of star power undoubtedly didn’t help, and neither did MGM’s tepid promotion. The film was swiftly shunted to the lower half of bills. But the film’s participants knew the quality of what they had made. Brown always cited it as a favorite, and Claude Jarman has said more than once that “Intruder in the Dust is the one I’m most proud of.” Ralph Ellison, however, gave the film its finest accolade. He wrote that of the whole cycle of race-based movies in 1949, Intruder was “the only film that could be shown in Harlem without arousing unintended laughter, for it is the only one of the four in which Negroes can make complete identification with their screen image.”

Watch: Original 1949 trailer for Intruder in the Dust (2:28)

Intruder in the Dust (1949). Directed by Clarence Brown. Written by Ben Maddow from William Faulkner’s novel. With David Brian, Claude Jarman, Juano Hernandez, and Elizabeth Patterson.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Google Play • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film at her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and in a column for filmcomment.com. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Post, The Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, The Criterion Collection, and Sight and Sound. Her novel Missing Reels is out in paperback from The Overlook Press.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.