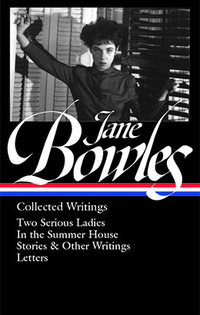

Arriving just in time for the author’s centenary, Library of America’s Jane Bowles: Collected Works is the most comprehensive edition ever published of the modernist pioneer (1917–1973) whom Tennessee Williams hailed as “the most important writer of prose fiction in modern American letters.”

Included are the novel Two Serious Ladies, with which Bowles debuted in 1943, the play In the Summer House (1954), all of her published short fiction, and several hitherto unpublished sketches and fragments, in addition to more than 100 of her letters.

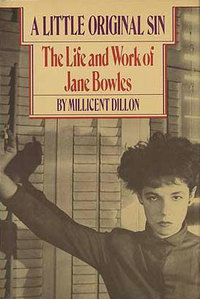

The volume’s editor is Bowles authority Millicent Dillon, the author or editor of four books on Jane and her husband, Paul Bowles, including the biography A Little Original Sin: The Life and Work of Jane Bowles (1981) and Out in the World: Selected Letters of Jane Bowles (1985). A fiction writer herself, Dillon has won the O. Henry Award for short stories of exceptional merit five times.

Library of America: You have been extensively involved with Jane Bowles’s life and work for several decades as a biographer, editor, and critic. When did you first become aware of Jane’s work and what did you respond to in her writing?

Millicent Dillon: I had never heard of Jane’s work until May 1973, when at the MacDowell Colony I met the writer Virginia Sorensen Waugh. We gave each other copies of our work and after reading my first published novel, she said, “There is something about your work that reminds me of Jane Bowles.” I said, “Who is she?” Virginia, who lived in Tangier and knew Jane, told me about her novel Two Serious Ladies. She then went on to say that at the moment Jane was very ill in a convent hospital in Malaga, Spain, where her husband, Paul, visited her every six weeks.

As it happened, though word had not yet reached the U.S., Jane had died a few days earlier. I returned to California and began to read Two Serious Ladies. From her first words something about what she told, something about what she withheld, her unique style and language, moved me deeply.

The notion of time in the work has as much to do with the evasion of time as with time passing. But there is also a holding to daily life with great passion. Her rendering of daily life is, however, filtered through an odd, slanting vision. Even as her characters talk about food and plain pleasures, they are obsessed with thoughts of sin and salvation. An individual sentence can begin one way and suddenly, halfway to its end, turn into something unanticipated.

Reading her work, I began to have the sense that her narrative method was more than a method, that it suggested it was the way Jane lived. I don’t mean to say that I thought her work was autobiographical in its detail but rather that the link between her life and her work was so powerful it imprinted on the fiction a sense of life lived and life told as indistinguishable.

One day in 1976, though I had never thought of writing a biography, I wrote to Virginia Sorenson Waugh who was back in Tangier and asked if she would tell Paul of my interest in writing about Jane’s life and work and see if he would be interested in helping me with the project. Shortly I received a letter from Virginia saying that she didn’t think anyone could write about Jane who hadn’t known her.

I took that for the final word until several months later I received a note from Paul Bowles. Obviously Virginia had changed her mind and had spoken to him about my projected biography. In his letter Paul said he would be glad to cooperate with me. He gave me the names of several close friends and relatives of Jane’s in the U.S. He also added, as if it were an afterthought, that Jane’s life had nothing to do with her work.

As I would find out in the course of doing a book on Jane and a book on Paul, it was a statement that did not apply to either of them.

LOA: How significant was Paul Bowles’s revision of the manuscript of Two Serious Ladies (originally called Three Serious Ladies)?

Dillon: In the early ’40s Paul and Jane were living in Mexico. Paul, who had been exempted from military service as a “neurotic personality,” was working on commissions to compose the music for various stage productions. Jane was working sporadically on her novel, even as she was becoming deeply involved in an affair with Helvetia Perkins, a forty-something-year-old American divorcee with a daughter close to Jane’s age.

One day in 1942, when Paul was in a sanitarium in Cuernavaca recovering from hepatitis, Jane brought her novel to Paul to read. Called Three Serious Ladies, the first section dealt with Christina Goering who pursues her destiny, not because it is “fun” but because “it is necessary to do so,” by attaching herself to gangsterlike men. The second involved Freda Copperfield, who goes to Panama with her husband and there starts a new life with the prostitute Pacifica. The final section dealt with three women in Guatemala, who are involved in pursuing ambitious but shady affairs with men.

Guided by his impeccable sense of classical form, Paul eliminated the Guatemalan section and tightened the novel to its eventual form as Two Serious Ladies. (The additional pieces are included in the LOA volume, titled “A Day in the Open, “A Guatemalan Idyll,” and “Señorita Córdoba.”)

When the novel was published in 1943, the critical reception was almost entirely negative. The effect on Jane was to make her ever more dismissive of her own talent.

For Paul, on the other hand, the act of revising Jane’s manuscript and his enthusiasm for what she had done convinced him that he wanted to return to writing fiction, a pastime he had pursued as a young boy.

In 1992, when I was in Tangier interviewing Paul for a book I was writing about him, on the last day of my visit he suddenly asked me, “Do you think it was a good idea to persuade her to cut out ‘Senorita Cordoba,’ ‘A Day in the Open,’ and ‘A Guatemalan Idyll’ from the novel?”

I answered him by saying what I believed, that artistically it was the right choice. But, I added, that if one does not speak in artistic terms, if one speaks instead of what these imagined beings were within Jane, I cannot guess what the consequences were for her of taking them out of the novel.

It is still a question I find difficult to answer. What if the form that mattered to Jane, that was instinctive in her, was one where characters come and go, walk onstage, walk offstage, and are indifferent to settled patterns?

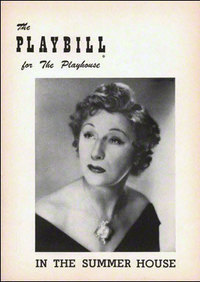

LOA: What can you tell us about the difference between the original version of In the Summer House and its final produced version?

Dillon: In the course of my research I was never able to discover the earliest version of the play, though I found a number of variants. It is clear, however, in all of the versions that the play is ultimately about the relationship between mothers and daughters.

The main characters are the middle-aged widow Gertrude Eastman Cuevas and her eighteen-year-old daughter Molly, whom Gertrude constantly harangues. Gertrude is considering marrying the well-to-do Mr. Solares and going off to Mexico with him. There is also a second mother, Mrs. Constable, who hovers over her fifteen-year-old daughter Vivian, who is wild and aggressive in finding pleasure.

Left alone after Gertrude goes to Mexico with Mr. Solares, Molly lives in a chaste marriage with Lionel, who works at a nearby restaurant but is contemplating becoming a religious leader or going into politics.

Unhappy in her marriage, Gertrude returns from Mexico and seeks out Molly.

The versions of the play that I found had several different endings. In one version Gertrude drags Molly away from Lionel, after convincing her that she is dangerous to others. In another version, Molly runs out and kills herself.

In yet another one, the final one, Molly goes way with Lionel and Gertrude is left alone.

Jane was pressured to choose this final ending by the theater people who surrounded her, whose judgment she respected. They told her that she must choose this ending in order for the play to be a success.

She gave in to these pressures but the play was ultimately not the success she had hoped for. Interviewed by Vogue as she was leaving New York to return to Morocco, Jane said, “There’s no point in writing a play for your five hundred goony friends. You have to reach more people.”

LOA: You have written or edited four books on Jane and Paul Bowles. What was it like to return to an intense engagement in her work for the Library of America collection?

Dillon: Starting in 1977, I had been deeply involved in writing Jane’s biography. After it was published in 1981, as A Little Original Sin, I worked on a collection of her letters, published in 1985 as Out in the World. In 1994 I edited a Viking Portable edition of the work of Jane and Paul Bowles, a volume in which I strategically placed excerpts from their work to show the deep connection between them. And then, though I had earlier refused to do this, I set out for Tangier once more to write a book about Paul. It was published in 1998 as You Are Not I.

When the Library of America contacted me last year about editing their projected volume on the work of Jane Bowles, I was gratified that, after many years of relative obscurity, Jane’s work was being granted the recognition it had long deserved. But I also had some questions as to what it would mean to me to return to my books on Jane and Paul after so many years.

I decided the first thing I must do was to reread all of Jane’s work. I was stunned, as I had been in my first reading, by the originality and emotional power of her work. In my rereading I came upon passages where there would be an unexpected turn in thought that would make me laugh out loud. Once again I was reminded of the remarkable alternation in her work between the ludicrous and the mystical.

In her letters, particularly the letters to Paul, I saw once again Jane’s struggle to convey with absolute precision what she was feeling and thinking at the moment of writing. She called her letters “agonizers,” as if it were a moral imperative to make her every word clear.

Her later letters, written after her stroke at the age of forty, reveal a different kind of struggle. She no longer possessed her astonishing early ease with words. Her vision had been affected but even more terrible for her was the fact that she felt she had lost the capacity to imagine. Still she persisted, trying to convey the sense of her ongoing life as clearly as possible.

Though all of this was a twice-told story for me, as I went over the material I was once again seized by the impact of her life and of her work. At this distance in time, I found myself meditating upon the oddness of my experience in writing the biography, in going to Tangier, in meeting Paul and all the other people, famous and not famous, who knew Jane. I had to acknowledge too how much chance and luck had paved the way for me in telling the story.

For example, I was in a water exercise class and one day I learned that one of the other participants was a woman who had once acted upon the Broadway stage. More than that, she had had a small supporting role in the production of In the Summer House and still had in her possession a diary of the production.

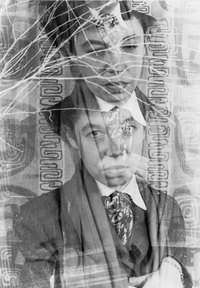

Another oddness: I read that a former classmate of mine in graduate school at San Francisco State had become a detective and was going to give a lecture about Dashiell Hammett. After his lecture, which was very amusing and informative, I went up to him and congratulated him on the talk. “So tell me,” he said, “what are you working on now?” “I’m writing a biography of someone you never heard of,” I said, “Jane Bowles.” “Jane Bowles?” he said, “my father, Karl Bissinger, took some wonderful photos of her.” And, indeed, the photo of Jane on the cover of my biography and on the cover of the LOA edition was taken by Karl Bissinger.

Yet another oddness: One day, as I was writing the book, I had lunch with a friend who worked at Stanford, where I had previously had a job as an “academic” writer for the News Service. My friend asked what I was doing and I said I was writing a biography of Jane Bowles. “Jane Bowles?” she said. “There is a professor in our department who once worked with her on some kind of speech therapy.” And indeed I was to meet this professor, who as a young man had worked with Jane after her stroke by having her write short essays. He had, moreover, saved those essays, which he showed to me, and they proved invaluable in my understanding of the effect of the stroke upon her.

And still another oddness: After I had signed a contract for the biography, my new editor told me that, as it happened, she was working with another writer whose mother-in-law, Miriam, had been Jane’s best friend in her childhood. From that contact came the chance to see her autograph album from school with its statement from Jane, written when she was twelve:

“You asked me to write in your book

I scarcely know how to begin

For there’s nothing orriginal about me

But a little orriginal sin.”

And there was yet one more coincidence or series of coincidences that began to manifest themselves over time as I pursued my research on the biography. Jane’s mother’s name was Claire, as was mine. Her maternal grandfather’s name was Louis, as was mine. She lived in Woodmere, Long Island from 1927 to 1930. I lived in Woodmere, across the tracks, in 1929 and 1930. At thirteen, after her father’s death, Jane and her mother moved to Manhattan to the very building where my family lived when I was born. Jane broke her right leg in 1931. I broke mine that same year.

Strange coincidences, yes, I admitted to myself, but don’t get carried way with them. Any idiot knows that one of the greatest dangers of being a biographer is confusing yourself with your subject. So beware of being misled by them. I did beware.