By Tom Shone

Undaunted by its literary pedigree, director Iain Softley and screenwriter Hossein Amini turn one of James’s challenging late novels into a brisk, satisfying two-hour drama—while keeping its dark heart intact.

“My pitch was that this was film noir,” said Hossein Amini of his screenplay for The Wings of the Dove, filmed by director Iain Softley in 1997. “The only difference is that they don’t literally kill each other, they just break the other girl’s heart and kill her that way.” These filmmakers did such a good job of turning one of Henry James’s densest, most difficult late novels into a brisk, satisfying two-hour drama that you must wonder whether such genre miscegenation isn’t the key to adapting the notoriously uncinematic James. His works are labyrinths, their closest cinematic cousins not Masterpiece Theatre or “Merchant-Ivory” but the thriller and horror film, twisty genres that honor James’s penchant for the rustle of veiled apprehension and shimmer of offstage machination. It’s no accident that the best adaptation of his work to date is Jack Clayton’s The Innocents, a version of “The Turn of the Screw” that honored the inky ambiguities at the heart of James’s might-be ghost story. Alfred Hitchcock didn’t bite when David O. Selznick tried to tempt him with that novella, but the director of Vertigo and Marnie would surely have thrilled to the streak of Pygmalion in The Portrait of a Lady—all of Gilbert Osmond’s cruelty and control. As for the air of epistemological confoundment that envelops the later work like fog, who among James’s most ardent fans hasn’t occasionally longed for Bogie to march in, cigarette hanging from his lower lip, and demand to get to the bottom of just what this Maisie knew, who told her and when?

Softley had never attempted period drama or a literary adaptation before; his previous pictures had been Backbeat (1994), a high-spirited film about the early years of the Beatles, and Hackers (1995), a lackluster thriller about a teenage computer whiz starring Angelina Jolie. Maybe that lack of pedigree helped. The plot of The Wings of the Dove, once distilled, wouldn’t seem out of place in the pulps—James himself called the material “ugly and vulgar.” A British beauty named Kate Croy, who has been taken under the wing of her rich Aunt Maud, is secretly affianced to a poor journalist, Merton Densher; if their romance were known, it would spell doom for the both of them. Into her aunt’s West London social circle comes a beautiful, good-hearted, naïve American heiress named Milly Theale, who is secretly very sick. Finding out about both her sickness and her fondness for Merton, Kate decides to encourage a romance between them, with a mind to Merton marrying Milly and then, upon her death, inheriting her millions. Then, she and Densher can reunite. During a trip to Venice, they proceed with their plan. But when Milly dies, fully cognizant of their duplicity, but still leaving Merton her money, shame fuels his belated devotion to the departed girl. In death, finally, he loves her. At the book’s end, Merton and Kate embrace, then recoil—“We shall never be again as we were!” They’re as unable to enjoy the spoils of their wickedness as Lana Turner and John Garfield in The Postman Always Rings Twice.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Henry James: Novels 1901–1902 |

James and film noir, it turns out, have a theme in common: the danger of sexual enthrallment. “What he fights is ‘influence,’ the impinging of family pressure, the impinging of one personality upon another,” wrote Ezra Pound about James in a brief essay from 1918. While this impinging took many forms (including financial) in his early works, in his later ones, starting with The Wings of a Dove (1902) and right through to The Golden Bowl, and his 1906 revision of The Portrait of a Lady, it is romantic and sexual. “His kiss was like white lightning, a flash that spread, and spread again, and stayed”—that’s how Isabel Archer reacts to Caspar Goodwood at the end of The Portrait of a Lady. It’s a prelude to one of the most famous, baffling acts of renunciation in the history of the novel, as she returns instead to Rome and her cold, controlling husband. “So had she heard of those wrecked and under water following a train of images before they sink.” The portents of doom are even stronger in The Wings of the Dove. “He laid strong hands upon her to say, almost in anger, “Do you love me, love me, love me? And she closed her eyes as with the sense that he might strike her.” And later, “The long embrace in which they held each other was the rout of evasion, and he took from it the certitude that what she had from him was real to her.” Who else but James could see an embrace as an evasion? Renunciations, betrayals, evasions, refusals, shutdowns—that’s what makes up the struggle for personal autonomy in James’s work. With his mortal horror of enmeshment, his motto might have been: Only disconnect.

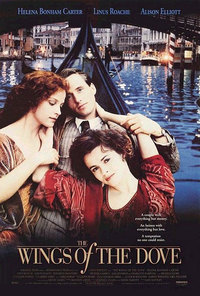

Amini and Softley’s first significant change is to move the action forward a few years from 1902 to 1910, from late Victorian to late Edwardian England. With modernity looming, Merton now talks of worker’s rights; women smoke at parties, where an air of Oriental licentiousness prevails; and the painting at which Milly gazes in the National Gallery is now not a Bronzino but Gustav Klimt’s 1908 semi-nude, Danae. And the kicker: Aunt Maud is played by Charlotte Rampling. That Softley should cast as his meddlesome, overdressed dowager—the “Britannia of the marketplace”—the onyx-eyed star of The Night Porter tells you all you need to know about his intentions. His film feels spongy with temptation: in the back rooms of bookshops, men peruse pornography, and at parties, innuendoes flow. The biggest change is to the character of Kate, here played by Helena Bonham Carter. In the book, caught between her impecunious father, manipulative aunt, and secret lover, she dares not struggle for fear of further enmeshment. As James renders it, her paralysis is prismatic, like that of an insect in amber. In the film, the forces pinioning her in place openly clash. Softley and Amini sketch her relationship with Densher (Linus Roache), already a year old, through a short series of scenes—an embrace on the Underground, a rain-soaked dash in the park—that double as the story of their courtship, before Aunt Maud declares, “If you ever see your friend again I can’t be responsible for you.” Kate’s heartbreak colors all that follows. “Does it hurt?” she asks Densher when she sees him at a party on the arm of another. She continues, “I hurt. So much. You can’t imagine.” But there is a glaze in her voice, a detachment from her own pain, which bespeaks a small imp of perversity now at work between them. “I want you to go back and kiss her with that mouth,” she tells him after breaking off their embrace—a foreshadowing of what she will ask him to do with Milly (Alison Elliott).

The filmmakers have done all this to cultivate sympathy for Kate. It does no damage to the book’s conception of Kate, for whose probity James himself felt the need to put in a plug: “It may be declared for Kate, at all events, that her sincerity about her friend, through all this time, was deep, her compassionate imagination strong; and that these things gave her a virtue, a good conscience, a credulity for herself.” The mixture of sincerity and venality is meat and drink for any actress. Helena Bonham Carter was about to kiss goodbye to her career in Merchant-Ivory films such as A Room with a View (1985) and Howards End (1992) with parts in David Fincher’s blisteringly nihilistic Fight Club (1999) and Tim Burton’s gothic fantasias. Her Kate Croy is a subtler filleting of her pre-Raphaelite ingénue persona: she gathers up all her tart impatience and uses her beauty as a mask: an elegant poker face. She’s like a Millais nymph as depicted by Bette Davis. “It’s in her eyes,” says Lord Mark, “Can’t you see? There’s so much going on behind those pretty lashes.” There’s a wonderful moment when Milly presses her to stay in Venice with her and Merton, and Kate resists. “I don’t want you to hate me,” she says. “Yes you will. If I stay, you will.” The moment is cobwebbed with dramatic irony—what she is doing is hateable—but Bonham Carter suggests, beneath the deceit, a palpable sincerity and sadness. Kate’s affection for Milly is real, along with the desire, in that moment, to be someone other than the person deceiving her—a very Jamesian mix.

The Wings of a Dove is a book honeycombed with secrets—Kate’s engagement to Merton, Milly’s sickness, their plot to secure her money. Those secrets, in turn, fan out into little deltas of secondary deception involving who knew what where, in whose company, whether they let on that they already knew, wished to pretend they didn’t, or genuinely didn’t have the foggiest. “Thank God they didn’t really know,” thinks Kate of her father’s disgrace. Milly and her companion Susan Stringham disembark at Dover “completely unknown . . . amid the completely unknowing.” “You all here know each other—I see that—so far as you know anything,” says Milly who is later “shaken by a knowledge” of Densher’s hatless head. After she dies (“she knew,” says Susan, “she knew”) it is left to Kate and Merton to attempt “to bury in the dark blindness of each other’s arms the knowledge of each other that they couldn’t undo,” as corrupted by it as Adam and Eve. Whether knowledge is here a metaphor for sex, or whether sex is a metaphor for knowledge, is the Moebius strip on which the work endlessly circles.

Some critics found that the movie reduced James’s nuanced, nimble prose to a bread-crumb trail of invented actions—a midnight gondola ride, a carnival, a shimmy up into the rafters of a restored church—and a prime instance of our old critical bête noire: illiterate, salacious Hollywood. “The problem is that once you posit an atmosphere of relative lubricity, most of the tension in the story disappears,” wrote Louis Menand in The New York Review of Books. “Who in this movie would care if Kate carried on a torrid affair with Merton Densher?” Well, Aunt Maud for one, and thus the rest of West London high society. This is so much huff-and-puffery. The carnality is decidedly there in the book, which either gains strength by omission, or elevates melodrama into art by the tasteful application of vagueness, depending on your point of view. “The play of one’s mind gave one away, at the best, dreadfully, in action, in the need for action, where simplicity was all,” Kate thinks at one point, a resentment in which it is just possible to hear an echo of the jeers that greeted James’s failed stage play, Guy Domville. All his his famous later works, in effect, raise a gentlemanly, Jamesian middle finger to any shared ground the novel might have with the dramatic arts. But in one area film is capable of giving James’s nuance a run for its money: the performance of its actors, as viewed in close-up.

In the shadow play of hesitation, suspicion, and swallowed scruple that Softley records flickering across the faces of his pas de trois, he makes great headway into the book’s dark heart, and even, in one aspect, improves upon it. Inspired by the memory of his beloved cousin Minny Temple who died from tuberculosis, the character of Milly was an attempt to wrap her memory in the “beauty and dignity of art.” As always with James, it sounds a little close to embalming. People are always comparing Milly to a work of art in the novel, aestheticizing her in a way James had already seen through in the character of Gilbert Osmond. It is Alison Elliott’s great gift to James to bring the dying Milly fully to life. Wearing scant makeup so we can register the natural bloom in her cheeks, Elliott is spirited and vigorous, even forward in a way that nonetheless carries the vulnerability of a watchful soul: a shy person daring to be bold, which is exactly who Milly is. “I’m going to make a fool of myself tonight” she confides to Merton on their night out in Venice, a date climaxing with a quick shin-up the scaffolding of a semi-restored church to look at the frescoes, a trip which anyone who has seen The English Patient knows is sure to lead to trouble. “I don’t want you to,” says Merton and the look of surprise on Elliott’s face—hurt to be rebuffed, touched by his thoughtfulness—is lovely.

Only Merton disappoints. It’s not Roache’s fault. The filmmakers have stiffened Densher’s backbone with socialist talk, but it’s hard to find an onscreen corollary for his essential passivity. He recedes off the page. “The difficulty with Densher,” writes James, “was that he looked vague without looking weak,” which sounds a little like a distinction in search of a difference. One wonders what an actor like Daniel Day-Lewis would have done with the part—probably demanded a rewrite, in order that we more fully feel the transfer of his affections from Kate to Milly, from feigned to real. While the first half of the film belongs to Kate, the tragedy of the second half should be his. As the action quickens to its climax, hurried along by Ed Shearmur’s thrumming score, Amini and Softley save their most audacious staging for last: an almost word-for-word version of the book’s final scene, in which Merton and Kate finally reunite, their victory now ash in their hands. The filmmakers relocate it from living room to the bedroom, where Kate disrobes like an automaton and lies for him on the bed, her back turned to him, waiting. Bonham Carter’s torso, with its accentuated ribcage, looks pale and shocking: if ever there was a time for this actress to climb out of the corsets and bonnets in which filmmakers seemed intent on wrapping her, this was it: not a love scene, but its opposite. Rain lashes the windows, as Densher, too, undresses. “I love you Kate,” he says, as if trying to convince himself. “I love you too” she replies, but the words just hang there as the two of them go through the motions in desolate long shot. Their lovemaking peters out. The last shot is of Densher’s face as he wrestles with his inability to lie to Kate, his back to her. As close as is physically possible, she nevertheless might as well be a million miles away.

So much for Hollywood salaciousness: Intimate yet lovelorn, the whole thing is about as erotic as a snuff movie. After finishing the film, Softley made the dreadful K-Pax (2001) with Kevin Spacey and then disappeared from Hollywood’s radar. Amini, on the other hand, went on to adapt Elmore Leonard’s Killshot in 2009, Patricia Highsmith’s The Two Faces of January in 2014 and, just this year, John Le Carre’s Our Kind of Traitor—a diet of treachery, extortion, and murder that would make lesser men blanch, but a summer breeze once you’ve tackled the late work of Henry James.

Original 1997 trailer for The Wings of the Dove (2:11)

The Wings of the Dove (1997). Directed by Iain Softley, written by Hossein Amini from Henry James’s novel. With Helena Bonham Carter, Alison Elliott, Linus Roache, Elizabeth McGovern, Charlotte Rampling and Michael Gambon.

Buy the DVD • Buy the Blu-ray • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Tom Shone is the author of Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer (Simon & Schuster, 2004), Scorsese: A Retrospective (Abrams, 2014), Woody Allen: A Retrospective (Abrams, 2015) and the forthcoming Tarantino: A Retrospective (Thames & Hudson, 2017)

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.