By Terrence Rafferty

The buoyancy, invention, and anything-goes spirit that the French director brings to David Goodis’s lower-depths novel Down There has the paradoxical effect of making this adaptation seem all the more American.

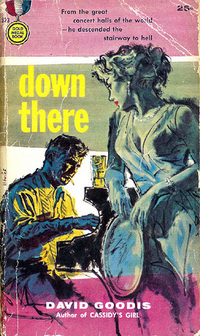

The kind of fiction we call noir is full of end-of-the-line men, luckless, alone, unknown. The distinction of the novels written by David Goodis (1917–1967) is that his male protagonists—“heroes” doesn’t seem quite le mot juste—actually relish their hopelessness, take a sort of strange comfort in it. They swaddle themselves in their melancholy, their solitude, their sweet anonymity. The main character of Goodis’s 1956 novel, Down There, is a museum-quality specimen of this rare type: formerly a concert pianist billed as Edward Webster Lynn, now just a guy named Eddie tickling the ivories for the sodden clientele of a Philadelphia dive bar. He has very little—no wife or girlfriend, not much money, a job for which he’s seriously overqualified—and he likes it that way. All he wants is to keep his distance from the mess of everyday life, to be “high up there and way out there where nothing matters.” An unsympathetic coworker describes Eddie as a “soft-eyed, soft-mouthed nobody whose ambitions and goals aimed at exactly zero. . . . It was almost as though he wasn’t there and the piano was playing all by itself.” With his studied self-effacement and his shoulder-shrugging indifference to everything other people care about, this wan, spectral being hardly seems American at all.

Actually, it was in France, not America, that David Goodis’s downbeat stories found their most appreciative readers, among them a young critic and filmmaker named François Truffaut. Down There, which had been published in the U.S. as a cheap Gold Medal paperback, appeared in France under the imprint of Gallimard’s Série Noire, which gave it a certain cachet among the America-obsessed intellectuals of postwar Paris. Here in the States, a Goodis novel was something to be read by men rather like his beaten-down characters, in motels or bus stations or cheap rooming houses; in France, it was a text to peruse over bitter coffee at Les Deux Magots and Café de Flore, in an idle hour between nicotine-fueled polemics. When Truffaut read it, he told a TV interviewer, “The book made me laugh out loud.” After a pause, he elaborated: “It both made me laugh and moved me.”

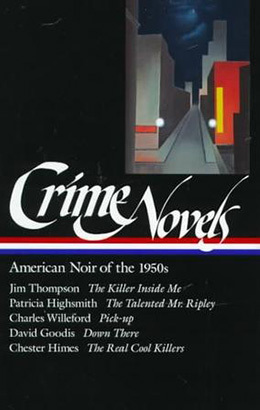

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1950s |

Which is exactly the right response to Down There, and to Goodis’s fiction in general—and for that matter to a fair amount of the American pulp enshrined (in hasty translation) in the somber-looking volumes of the Série Noire. Truffaut, who was nearly as indefatigable and as astute a reader as he was a moviegoer, saw the comedy in even the bleakest noir, and understood the genre’s odd similarity to farce, in the cascading awfulness of the calamities visited on their characters. The novel’s heroine sees in Eddie a resemblance to Charlie Chaplin: another small man who wants to be left alone (and never is), who can make you laugh and move you. When Truffaut filmed the novel, as Shoot the Piano Player, in 1960, he didn’t go full Chaplin—you never go full Chaplin—but he heightened both the humor and the pathos of Goodis’s low-down Philly noir.

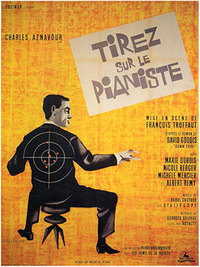

Shoot the Piano Player relocates the story’s action to Paris (and, late in the film, a snowy patch of French countryside), adds a couple of minor characters, and changes a name here and there: the pianist, played by Charles Aznavour, is now Edouard Saroyan, and goes by the nom de dive Charlie Koller. Otherwise, Truffaut and his cowriter, Marcel Moussy, stick pretty closely to the novel’s plot and even its peculiar structure: in the film, as in the book, a long flashback interrupts the action about halfway through. But the action in both is on the basic side, anyway—a series of chases, captures, fights, and conversations, with a light dusting of sex. In Shoot the Piano Player’s opening sequence Charlie (we’ll call him that) has his peaceful evening at the café interrupted by the breathless appearance of his brother Chico (Albert Rémy), who’s on the run from a pair of angry thugs. Impulsively, he helps Chico escape, and spends the rest of the movie regretting it. His unthinking, almost casual action, toppling a stack of crates to cover his brother’s getaway, implicates him in other people’s problems. It takes him from his preferred “high up there” down to a place where he might be forced to care about somebody else: specifically, his family—he has three brothers, two of whom are crooks—and a comely coworker named Léna (Marie Dubois), who are now all in mortal danger. The cover line of the original Gold Medal paperback reads, “From the great concert halls of the world—he descended the stairway to hell,” and while that might at first glance seem a tad over the top, it is, in this character’s terms, weirdly accurate. For Eddie/Charlie, hell really is (as a Frenchman once wrote) other people.

Though you wouldn’t want to stretch the comparison, there’s a sense in which Goodis, like his protagonist, was on the down staircase of his career. He’d published his first novel when he was just twenty-one years old. A decade before Down There, his novel Dark Passage (1946) had been serialized in The Saturday Evening Post, published in hardcover, and optioned for the movies; the film, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall and directed by Delmer Daves, came out in 1947, and did well. Warner Bros. brought him out to Hollywood and put him under contract to write screenplays. But the contract wasn’t renewed, and Goodis headed back to Philadelphia to crank out the moody paperback pulp that was his true métier. In the ’50s, a couple of lower-budget, less starry pictures based on his work—Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall (1956) and Paul Wendkos’s The Burglar (1957)—kept him barely visible, but he certainly wasn’t a household name. (Not in the better literary households, anyway.) He was drifting into obscurity.

Truffaut was going in the opposite direction. In 1959, his semi-autobiographical debut feature, The 400 Blows, was the first great triumph of the French New Wave, winning him the best director award at the Cannes Film Festival and selling a lot of tickets in France and the United States. He was under thirty, about the same age Goodis was when Dark Passage was a hot property. As a followup to the lyrical 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player wasn’t, to say the least, an obvious choice. (And as it happened the film was less successful both critically and commercially.) But Truffaut saw something that suited his own sensibility in Goodis’s scruffy underworld romanticism. In retrospect, Charlie Koller, as Aznavour plays him, seems the prototype of a sort of male character who would appear frequently in Truffaut’s films over the next couple of decades: reserved, diffident, melancholic, often obsessive. That character would be played by Oskar Werner in Jules and Jim (1962) and Fahrenheit 451 (1966), by Jean-Louis Trintignant in Confidentially Yours (1983), and by Truffaut himself in The Wild Child (1970), Day for Night (1970), and The Green Room (1978). Like Goodis, he felt an affinity for quiet, watchful men.

According to Philippe Garnier’s hugely entertaining sort-of biography Goodis: A Life in Black and White (2013), the novelist on the skids and the director on the rise met only once, briefly, in New York, and Goodis didn’t make much of an impression; the meeting, Truffaut later said, was “a blur.” Goodis seemed to have liked the movie, but, Truffaut wrote, “he was less happy when he saw [the film] with subtitles than when he didn’t understand any of the dialogue and had believed the film to be much more faithful to the book.” Georges Delerue’s sad, lovely music must have suited his congenitally dreamy-depressive mood (this was the first of eleven scores the composer wrote for Truffaut), and Aznavour’s mournful demeanor may have seemed to him the very image of Eddie Lynn—his character to the death-in-life. But it’s curious that, even without subtitles, Goodis could have missed the enormous differences in tone and rhythm between Down There and Shoot the Piano Player. “I think Goodis’s voice comes through in the film,” Truffaut said, maybe a little defensively, twenty years later, and he’s right. It’s just that the voice seems to have been recorded at another speed.

Or, rather, at several speeds, only one of which is recognizably that of the novel. In all his novels, Goodis writes like a man in the grips of an obsession, without much variation in intensity. It’s both the strength and the weakness of his best work: his books are like extended reveries, and you can lose yourself in them, but their mood is relentless. The ruling passion of both his writing and, apparently, his life was something the French have an expression for: nostalgie de la boue, an attraction to low places—literally, the mud. Like the men he wrote about, he was stuck there, and happily. Reading Down There, you may begin to suspect that the mood is unchanging simply because it is, for the writer, so deeply pleasurable: this down-and-dirty existence isn’t his nightmare, but his fantasy. This does not describe the temperament of the artist who adapted this novel for the screen. “I’ve always had a passion for changing tones,” François Truffaut once said.

And change them he does in Shoot the Piano Player, from ragged gangster action to casual lyricism to eroticism to out-and-out slapstick and finally to something akin to tragedy—all with one small, dark, puzzled man watching and sometimes tinkling out a tune or two mechanically, as if the piano were playing itself. Truffaut, a better pianist, sets his mercurial editing rhythms and leaping tones against the steady beat of Goodis’s peculiar, unvarying fantasy, and comes out with something that feels like an inspired improvisation on noir themes. The buoyancy, the invention, and the anything-goes spirit that this Frenchman brings to Goodis’s glum material makes the whole thing seem more, well, American. It’s jazz.

Shoot the Piano Player (1960). Directed by François Truffaut. Screenplay by Truffaut and Marcel Moussy based on the novel Down There by David Goodis. With Charles Aznavour, Marie Dubois, Nicole Berger, and Albert Rémy.

Buy the Criterion Collection DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes

Terrence Rafferty is the author of The Thing Happens: Ten Years of Writing about the Movies. He is a frequent contributor to The New York Times, The Atlantic, and DGA Quarterly.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.