By Farran Smith Nehme

In this 1963 adaptation of The Haunting of Hill House, atmosphere, understatement, and masterful off-kilter camerawork combine to preserve the “elusive mastery” of Shirley Jackson’s modern classic.

Suppose it is a dark and stormy night in 1959, and you are reading The Haunting of Hill House, the new novel by Shirley Jackson. In between trips to make sure the windows are bolted and the door is locked, you soothe yourself by casting the movie. Who should play the main character? Or rather, what should play the main character? The true protagonist isn’t Eleanor Lance, the lonely spinster who goes to Hill House only to find that it wants to lure her into some kind of hellish adoption. The main character is there in the title. What should Hill House—“vile,” as Eleanor calls it—look like?

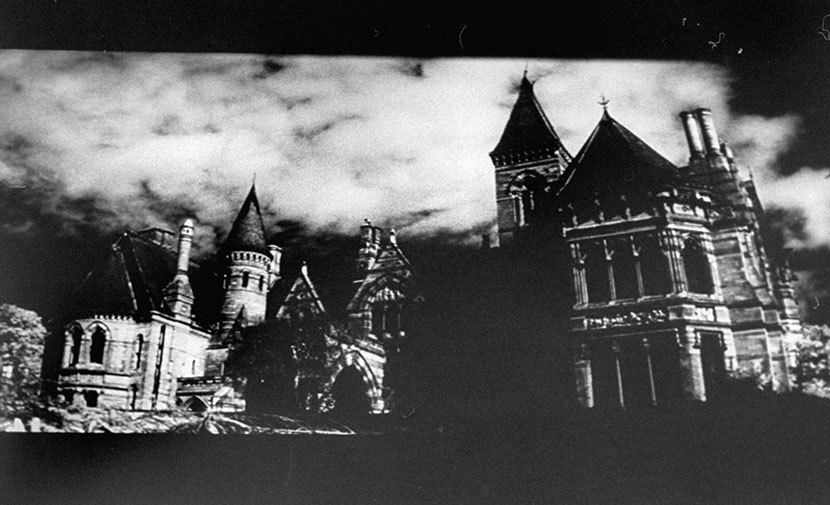

Jackson is vague on this topic; Hill House is a large New England mansion and in some ways it’s almost cozy, with “folds of velvet and tassels and purple plush,” as Jackson writes. For 1963’s The Haunting, director Robert Wise and Elliot Scott, the production designer, chose England’s Ettington Hall to represent Hill House, and this pile of stone is well cast: huge, vaguely medieval, with turrets and clustered windows, heavy doors and columns. It sits imposingly at the top of a slope and, thanks in part to cinematographer Davis Boulton, seems to blot out the light even at midday. The overall effect is a cross between a church and an insane asylum, and the real-life building, you will not be surprised to hear, is also said to be haunted.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| Shirley Jackson: Novels and Stories |

“Diseased, sick, crazy . . . a deranged house,” is what Dr. Markway (Montague in Jackson’s novel) calls it. Played by smooth-voiced, solidly handsome Richard Johnson, paranormal researcher Markway has asked a number of psychically attuned young people to stay with him in the mansion and see what manifests itself. Only two show up: Eleanor, all milky pallor and jangled nerves as played by Julie Harris, and Theodora (Claire Bloom), an artsy, cat-like beauty whose cool will shortly unravel. Theo is a lesbian—a suggestion from Jackson that is considerably more obvious in the film—and perhaps attracted to Eleanor; Eleanor, in turn, develops a timid crush on Dr. Markway. The fourth temporary occupant, Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn) is in line to inherit Hill House. He’s there to keep an eye on his property, serve martinis, and to be the voice of reason, via remarks like “Don’t give me any of that supernatural jazz.”

Inside the house is where the filmmakers got it most brilliantly right, because their Hill House isn’t a spare, somber mausoleum, like the stone castles in the great Universal horror pictures like Frankenstein and Dracula, nor is it “padded” and “soft” as Luke describes it in Jackson’s novel. Instead, at Elstree Studios the designers created a visual riot. Every door and panel and cornice is carved, crazy patterns of flowers and vines tumble across the rugs and furnishings, ghastly paintings and sculptures abound, mirrors and highly polished floors reflect back uneasy faces. Each table is crowded with sinister figurines as well as examples of that creepiest of all nineteenth-century fads, dead flowers under glass. The rooms seem to oppress the characters with all these things. The main staircase and the hallways are emptier, it’s true, but who wants to hang out in the hallways, where every door looks alike and is ready to swing shut without warning?

Once everyone assembles, it doesn’t take long for spirits to begin tramping down the halls. On night one, Eleanor and Theo wind up clinging to each other while what sounds like Hannibal’s elephant paces the hall and something slowly, slowly turns the doorknob. A few nights later, they have (understandably) decided to sleep in the same room, and Eleanor lies awake, listening first to thumps that sound like monstrous footsteps, then to the hopeless sobbing of a child. She moans to Theo not to clutch her hand so hard, while the half-light of the room shows a whorled pattern in the woodwork that resembles a malevolent face. Finally she screams out loud and a light is switched on—by Theo, who was asleep on the far side of the room. “Oh my god,” gasps Eleanor, “whose hand was I holding?”

Whose, indeed. Shirley Jackson would never be so banal as to tell you, and neither does the film. Hill House has been the site of “scandal, insanity, murder, and suicide,” Markway informs us, and we see it all in an opening flashback. The wife of Hugh Crain, the cold and evil man who built the house, dies in a horrible carriage accident on the driveway without ever coming within view of the door. Hugh’s second wife falls down the stairs after seeing we know not what; Hugh’s neglected daughter spends her life in the house only to expire as an old woman calling for help to a paid companion who never comes; and finally, the companion inherits the house and hangs herself in the library.

Any of those four dead women would make a good ghostly candidate, and Hugh Crain’s malevolent spirit brings the total to five, considering how malign Hill House is, and how often he is addressed and discussed by the living characters. But in the world of the film, it could be all of them, or more terrifyingly, none—just the house itself, born bad, searching for someone else to spend eternity there. As Theo says to Eleanor, “It wants you, Nell.”

But there is also the possibility that Eleanor, who qualified for this paranormal experiment because of a poltergeist that manifested as stones raining on her mother’s house, has brought the evil with her. Screenwriter Nelson Gidding visited Shirley Jackson and eagerly suggested, as Edmund Wilson had with “The Turn of the Screw,” that the ghosts were all in the lady character’s neurotic mind. Jackson told him that was a nice idea, but this was a ghost story. Jackson believed in spells and vibrations, in houses that had personalities and preferences about their human residents. Events can be read as happening in Eleanor’s mind, I suppose (although that leaves all the things seen by the other characters unexplained). But whether or not Jackson was merely being polite with Gidding when she called his inspiration “nice,” her idea is better. A haunting is more mysterious than a nervous breakdown.

Jackson’s prose is sharp, cool, factual, built of sentences that only seem simple. She lived in Vermont with a famous husband, the literary critic Stanley Hyman, and four children. In between cooking, washing, and the thousand cares of a mid-century wife and mother she crafted humorous domestic stories that paid the bills and still charm. And she also wrote The Haunting of Hill House, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and stories such as “The Lottery,” “The Tooth,” and “The Witches,” where, with a few deft twists, ordinary American life turns into horror.

She was a writer of enormous subtlety. Witness the famous opening lines of The Haunting of Hill House:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

It is typical of Jackson’s elusive mastery that the most terrifying part of that paragraph is the last comma: “. . . whatever walked there, walked alone.” Punctuation, needless to say, is not in the filmmaker’s toolbox. Larks and katydids, too, are not easy to work into a script. Wise cut his directorial teeth working for the legendary Val Lewton at RKO, and liked to tell interviewers that his spooky film was a tribute to the way a Lewton film worked almost entirely through suggestion. “I didn’t show anything. It was just suggestions. There is nothing in it,” he said. That’s essentially true; the closest thing to a special effect is a moment when a door begins to ripple and bend from the force of whatever ghastly spirit is trying to get at the characters. (In reality, it was a low-tech matter of having burly crew members push beams against the other side of the door.)

But Wise also said, “I had a marvelous cinematographer.” Boulton’s camera is what truly creates the spooks: Dutch angles that tilt the characters, dolly zooms that keep Julie Harris the same size as the background around her shifts. “All of the doors are slightly off-center . . . there’s not a right angle in the place,” says Markway of Hill House, and that often seems to be true of the filming, as well. One throat-clutching moment comes as Eleanor looks up at the tower where a prior occupant hanged herself. The camera shifts to look down at Eleanor looking up—and then the shot plummets, like the dead body itself falling on Eleanor.

In 1999 The Haunting was remade in garish color and filled with CGI manifestations of what Shirley Jackson and Robert Wise had given us credit for being able to imagine on our own. For those of us who love it—including Guillermo del Toro, Martin Scorsese, Chuck Palahniuk, and Stephen King—The Haunting needs no embellishments.

1963 trailer for The Haunting (2:33)

The Haunting (1963). Directed by Robert Wise. Written by Nelson Gidding from Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House. With Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, and Russ Tamblyn.

Buy on Blu-Ray • Buy on DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Google Play • Watch on Vudu

Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film at her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and in a column for filmcomment.com. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Post, The Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, The Criterion Collection, and Sight and Sound. Her novel Missing Reels is out in paperback from the Overlook Press.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.