By Michael Sragow

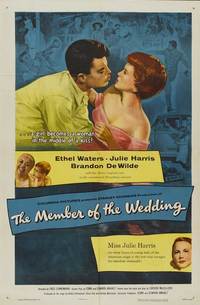

Fred Zinnemann’s sensitivity and intelligence, working in tandem with a trio of extraordinary lead performers, turn Carson McCullers’s novel and successful stage play into one of the screen’s great coming-of-age stories—one that is too little appreciated today.

Fred Zinnemann had marvelous range and directed classics of many kinds, including The Men, From Here To Eternity, High Noon, The Nun’s Story, The Sundowners, The Day of the Jackal, and his “official” classic, A Man For All Seasons. But his greatest film and his own personal favorite was perhaps his least popular and celebrated: his 1952 adaptation of Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding. Sixty-five years later, no other American director has created a female coming-of-age film that compares to it in casual profundity and insight. Zinnemann pitches us into a Southern hamlet based on Columbus, Georgia, where twelve-year-old Frankie Addams (Julie Harris), her seven-year-old cousin John Henry (Brandon deWilde), and Frankie’s surrogate mother, the cook and housekeeper Berenice Sadie Brown (Ethel Waters), conjure a universe of yearnings. They mostly just hang out in the kitchen of a drab middle-class home at the tail end of a long, hot summer, yet the film soars on the alternately fierce and tender interplay of these brilliantly drawn characters.

The Member of the Wedding caught the zeitgeist as a best-selling novel (1946) and a surprise smash play (with the same principal cast as the movie, directed on Broadway by Harold Clurman in 1950). But Zinnemann’s film did not enlist the same legions of fans. Sadder still, few critics championed this filmmaker’s tough-minded sensitivity and humanism when American audiences were ready to rediscover it, in the 1960s and 1970s. For years, the only way you could get a home video copy of his Member of the Wedding was in a DVD box dedicated to the work of its producer, Stanley Kramer, who was often overly possessive about movies other men directed. Those who discover the film on its new Twilight Time Blu-ray will savor its robust period flavor and astonishing pertinence.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| Carson McCullers: Complete Novels |

At the outset, the script’s one voiceover passage tells us that for Frankie, “This was the summer when for a long time she had not been a member, she belonged to no club and was a member of nothing in the world. Frankie had become an unjoined person and she was afraid.” Frankie’s mother died at childbirth, her father is aloof or distracted, and a close friend her own age has moved away. Older girls shun her. The ones who get together in a clubhouse abutting her backyard may be, as Berenice says, “fully two years older” than Frankie, but she’s miserable when they don’t vote her into their social club. She desperately needs to think she’s more mature than young’uns like John Henry. To make things worse, she has just experienced a growth spurt that leaves her feeling like a carny freak.

“And then,” as the voiceover goes on to say, “on the last Friday of August, all this was changed, it was so sudden that Frankie puzzled the whole blank afternoon, and still she did not understand.” What happens is that her serviceman brother Jarvis (Arthur Franz) stops at home with his girl Janice (Nancy Gates) to announce that they’ll be married the next weekend. Frankie projects herself onto their bliss. She declares that the wedding will change her life too, because Jarvis and Janis are “the we of me.” She fantasizes that they will take her with them and then lead her on a globetrotting life. McCullers’s dialogue, taken mostly from her play (with added bits like the voiceover from her novel), distills prose into a poetry that’s equally economical and evocative. (Edward and Edna Anhalt wrote the screenplay.) The genius of McCullers’s conception is that Frankie’s delusionary bout of wishful thinking is itself a rhapsodic leap for a girl who is alienated and adrift, stuck at home while dreaming of the world. The Member of the Wedding traces the vertiginous gap between childhood and adulthood and the dizzying contours of all-American loneliness.

Frankie feels disconnected from everyone and self-conscious about everything. Typical of McCullers’s devastating eye for detail, Frankie fears that the older girls “have been spreading all over town that I smell bad. When I had those boils and had to use that black, bitter-smelling ointment, old Helen Fletcher asked what was that funny smell I had. Oh, I could shoot every one of them with a pistol.” Movie directors often get so nervous around heightened language that they either neuter or embalm it. Not Zinnemann. He takes on the challenge with tactile intimacy and intelligence. This movie detonates McCullers’s primal lyricism.

The director and his cinematographer, Hal Mohr, bring us so close to Frankie’s flesh that when Berenice complains about her “rusty elbows” we want to scour them ourselves. Frankie says, “I never believed before about the fact that the earth turns at the rate of about a thousand miles a day. But now it seems to me I feel the world going around very fast. I feel it turning and it makes me dizzy.” Harris breathes excitement and wonder into her tween limbo. And Zinnemann captures Harris’s fantastic ebullience turning to hysteria as she lunges and twirls before his subtly moving camera. Emotional turbulence flickers across her face. She’s a force of her own nature, whether she’s tossing a knife at the kitchen door or using the blade to gouge out splinters. The question is, will she be able to harness her energy for good—especially, her own good.

In The Novel Now (1967), Anthony Burgess contends that misfit kids like Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in The Rye are “at least the symptom of a need, after a ghastly war and during a ghastly peace, for the young to raise a voice of protest against what the adult world was doing, or failing to do.” More generally he argues that in mid-century American fiction, “the typical hero is a child or adolescent, bearing a half-realized innocence through the dirty world.” What Burgess writes applies emphatically to Zinnemann’s movie. By keenly observing a specific milieu—depressed postwar Dixie, still in the thick of Jim Crow—the director summons a rich, immediate, and universal experience. Zinnemann, like McCullers, parallels Frankie’s pumped-up feelings of entrapment with the actual persecution of Berenice’s restless foster brother, “Lightfoot” Honey Camden Brown (James Edwards), an under-employed jazz trumpeter. Race turns accidents involving white men into catastrophes for Honey. In everyday life, Frankie’s father riles him with his presumption that any black man would substitute, without notice, for a porter at Mr. Addams’s jewelry shop.

The Member of the Wedding is one of the great coming-of-age stories partly because it links Frankie’s recognition that her mind and body are out of whack with her growing knowledge that society is off-balance, too. Today the film seems prescient for attacking the media-bred illusion that modern life has brought everyone together. Once Frankie decides that she belongs with Janice and Jarvis, she feels empowered to walk up to anyone in town, introduce herself, and explain her getaway plan. The movie is never more distinctively comic than when she sallies forth on the power of her own euphoria. She begins calling herself “F. Jasmine,” so she’ll have a “J” name, just like Janice and Jarvis. She fantasizes that “the we of me” will be called on to give national radio interviews, “some eyewitness account about something,” as if she has entered the secret center of a hitherto unknowable universe. The film is never more upsetting than when Frankie indulges in manic visions of touring each continent and being embraced by strangers everywhere. “We’ll just walk up to people and know them right away. We’ll be walking down a dark road, and see a lighted house and knock on the door, and strangers will rush to meet us and say, ‘Come in! Come in!’ We will know decorated aviators and New York people and movie stars. And we’ll have thousands and thousands of friends. We’ll belong to so many clubs that we can’t even keep track of them all. We will be members of the whole world!” Zinnemann balances McCullers’s piercing comic awareness with her rigorous kind of poignancy. Frankie is so anxious to grow into a more adult and worldly identity she doesn’t realize that she’s lucky enough to have the love of Berenice and John Henry, her authentic family.

It’s a testament to the range and power of Harris’s performance that we respond with equal empathy to Frankie’s naïve wistfulness and outrageous rants, to her naked vulnerability and her delusional arrogance. Harris, twenty-six when she starred in the movie, does something that resembles what Judy Garland did when she played Dorothy—she imbues pre-adolescent emotions with adult intensity without violating the integrity of either. And Ethel Waters’s Berenice matches her all over the emotional spectrum. The way Waters interprets her, Berenice is more than a surrogate mother: a friend, a guidance counselor, a referee, and even a priest. A woman who has married four times (only once happily) and lived in Chicago as well as in Georgia, she brings her wisdom into the kitchen with a sureness and warmth that make Frankie and John Henry see her eye to eye—that is, the one eye she has left (the other is a glass eye or an eye patch).

What gives Berenice clout is her willingness to use her own mistakes to analyze Frankie’s. As Frankie tries to force a connection to Jarvis and Janice’s marriage, Berenice explains that her own eagerness to see pieces of her beloved first husband in other men led her to marital disasters. (Her realization that one of her marriage stories is too racy for her youthful audience and she must pull it back is one of the film’s comic high points.) Frankie confesses to Berenice that on her bike-ride through town on a “frying hot” day, “just as I passed this alley, I caught a glimpse of something out of the corner of my left eye. A dark double shape. And this glimpse brought to my mind—so sudden and clear—my brother and the bride that I just stopped and couldn’t hardly bear to look and see what it was.” When she did look, what she saw “was just two boys. That was all. But it gave me such a queer feeling.” Berenice responds that she knows exactly what Frankie means. “You mean right here in the corner of your eye you suddenly catch something. A shiver runs through you. You whirl around. And stand there facing you don’t know what. But . . . not who you want. And for a minute you feel like you’ve been dropped down a well.” With a voice full of kindness and awe, Waters brews up a whole other dimension of reality, where the psychological meets the supernatural.

In the rolling Southern rhythms of her novel, McCullers writes, “Often on these summer evenings they would suddenly start a song. Often in the dark, that August, they would all at once begin to sing a Christmas carol, or a song like the Slitbelly Blues. . . .” In the play and the movie, they unite on “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” and it carries them all to a pinnacle of grace. Waters mingles bone-deep melancholy and rapture when she sings, “Why should my heart be lonely, away from heaven and home / For Jesus is my portion / My constant Friend is He / For His eye is on the sparrow, and I know He watches me.”

Zinnemann’s handling of this hymn just about defines sensitivity in directing. John Henry, with one of those strokes of childhood genius that informs his entire character, starts to sing it when he sees Frankie upset and exhausted on Berenice’s bosom. Berenice ends it as soon as she senses that some healing emotion has worked its way into Frankie’s bony frame, which she calls “the sharpest set of human bones I have ever felt.” The harmony of these three performers, in this hymn and throughout the movie, is transcendent.

Brandon de Wilde’s role is smaller than the others, his presence more diminutive, but his contribution is enormous. Has there ever been a more unexpected and mischievous depiction of a towhead? Disarming, affectionate, and unpredictable, he swiftly supports Frankie’s flamboyant choice of a dress for the wedding. But when Berenice says it makes her look like “a Christmas tree in August,” the description so opens his eyes and delights him that he just as quickly turns on Frankie. De Wilde effortlessly embodies how shards of logic and illogic lodge side by side in an unformed mind. And he’s superb at depicting how John Henry tries to take Frankie’s emotional temperature when he’s deciding whether to spend time with her and even agree to a sleepover.

The loving gaze that envelops each of them is Zinnemann’s, and it’s all-encompassing. A master of composition, he makes us feel as if we’re sitting in at the kitchen-table bridge game, absorbing Frankie’s frustration when John Henry won’t honor the rules, leaning in when Berenice suspects the boy of stealing the face cards. Zinnemann brings us so far into the world of this movie, so deeply into Frankie’s psyche, that her humiliation at the wedding—her father dragging her from the honeymooners’ car and dropping her in the street—has the impact of a bloodbath in a war film. The movie ends abruptly but correctly, as if the director knows the exact end-point for this portion of Frankie’s youth. Zinnemann was frequently a master, but never more so than in this movie. In The Member of the Wedding, his eye was on the sparrow.

The Member of the Wedding (1952). Directed by Fred Zinnemann. Written by Edward and Edna Anhalt, from the novel and play by Carson McCullers. With Julie Harris, Ethel Waters, and Brandon deWilde.

Buy the Twilight Time Blu-ray

Michael Sragow is the curator of Library of America’s Moviegoer feature. He is a programmer for The Criterion Channel, Contributing Editor and online movie critic for Film Comment, and author of Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.