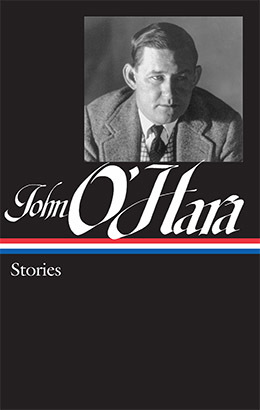

The latest entry in the Library of America series, John O’Hara: Stories brings together sixty short works by the twentieth-century realist described by Edmund Wilson as the “master of the short-story sketch” and by Fran Lebowitz as “the real Fitzgerald.”

Edited by Charles McGrath, the new LOA volume is both the largest collection of O’Hara’s short fiction ever published and the first to be annotated with extensive notes clarifying his allusions to several decades’ worth of music, movies, fashion, and topical events.

Formerly deputy editor at The New Yorker and editor of The New York Times Book Review, McGrath is currently a writer at large for The New York Times. In the following interview, he delves into the traits that make O’Hara a modern master of the short story.

LOA: Why John O’Hara, and why now? Is his work particularly ripe for reassessment in 2016?

McGrath: Why now? If you ask me, a reconsideration of O’Hara is long overdue. He’s an important American writer who has been unjustly neglected, overshadowed by his even more gifted contemporaries Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Faulkner. Partly that’s his own fault. In person he could be sweet and generous, but his public persona was prickly and blustery, even a little obnoxious at times. He made it easy to dislike him. He’s also better-known, probably, for his novels, which eventually became loose and baggy—best-selling doorstoppers.

But the O’Hara who most interests me is O’Hara the short story writer. He’s actually a crucial figure in the development of the American short story, with links to Hemingway and Fitzgerald, on the one hand, and on the other, to a generation of writers he influenced: Salinger, Updike, Cheever, Raymond Carver. O’Hara is a master of dialogue, and also a great observer of things. If you want to know what it looked and felt like to live in Prohibition-era America, for example, I can’t think of a better place to start. He’s also perhaps the most discerning writer ever on a subject Americans don’t like to talk about much: social class.

LOA: O’Hara wrote some four hundred stories over the course of his career; you’ve selected sixty for this collection. What did you discover, or rediscover, in the course of working your way through such a large body of work?

McGrath: Perhaps the biggest surprise was the consistency of the stories, which made choosing among them very difficult. There are maybe a dozen genuine masterpieces, stories that anyone would agree deserve to be in an O’Hara anthology, and roughly the same number of duds—stories that for me, anyway, didn’t quite seem to come off. That leaves an enormous middle ground, and I went over and over the stories, changing my mind all the time about which to keep. Without my quite intending it, the final selection does, I think, show O’Hara in all his range and variety, and that’s perhaps the other big surprise—how many different kinds of stories he wrote, and about how many different worlds. Not just Gibbsville, Pennsylvania—his version of Pottsville, where he grew up—but also New York and Hollywood.

LOA: Fran Lebowitz has stated that O’Hara, “that great American chronicler of convention, was not only deeply unconventional, but also experimental.” Do you see that experimental side in these stories?

McGrath: It’s in the stories—most of them written for The New Yorker—that he was most able to be experimental. With the novels there were commercial pressures and expectations, but with the stories he could try things out. The only people he had to please were himself and the magazine’s editors, who encouraged the experiments. In his early work especially you see him discovering the possibilities of the short story as he goes along. He started with sketches, little scenes or slices of life, and then learned how to expand them into something larger, without losing a sketchlike quickness and economy. They grab your attention before you even know where they’re going.

LOA: O’Hara in his stories is very sensitive to distinctions of class—something Americans tend to downplay, at least in public. Is his insistence on the centrality of class connected to his relative neglect, until recently, by the literary establishment?

McGrath: It’s hard to know why the critical establishment so took against O’Hara. He didn’t like the critics any better than they liked him, and in the prefaces to some of his collections said some pretty outrageous things and made overly grand claims for himself. So there was a sort of ongoing feud between him and the critics, at least a few of whom probably held O’Hara’s financial success against him.

Some of the critics did complain that O’Hara dwelled too much on issues of social class, but I think they misunderstood where he was coming from. O’Hara was not a defender or snobbish celebrant of the American class system, but a careful observer of it. He understood how arbitrary and unfair it is, how rigid and fragile it can be at the same time—a maze of envy, snootiness, and insecurity. Nor is social class the actual subject of most of the stories. It’s more nearly the atmosphere his characters breathe, or the carapace they’re trying to wriggle out of.

LOA: One eye-opening aspect of these stories is that O’Hara’s women characters have libidos and aren’t at all demure about it. Did this frankness ever lead to censorship issues, either at The New Yorker or with book publishers?

McGrath: The novels were always turning up on dirty-book lists, and Ten North Frederick was even banned in Michigan for a while and O’Hara and Bantam Books, who published the paperback, were prosecuted for obscenity in New York. (The charges were eventually dismissed.) At The New Yorker, O’Hara knew the rules. He complained about them all the time, but he lived with them. As far as I know, no story of his was ever turned down there because it was too sexually explicit.

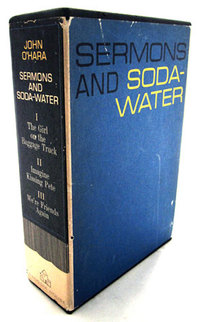

But there was a near-crisis over the novella-length story “Imagine Kissing Pete.” O’Hara submitted it to the magazine, after a ten-year feud in which he published almost no stories, on the condition that not a single word could be changed. The editors agreed, but then at the last minute, as the magazine was going to press, William Shawn, the editor in chief, decided that an oral-sex scene, involving a baby sitter and some guy she has picked up, went a little too far. So a very anxious phone call needed to be made. Would O’Hara blow up and stalk away for another ten years? He laughed and said, “I was wondering when you’d pick up on that.”

LOA: First-time O’Hara readers may be surprised to learn that the short fiction extends deep into the 1960s and faithfully reflects an era when, as you mention in your Editor’s Note, “Lyndon Johnson is president, and people who used to go to bars or speakeasies are staying home and watching television.” How would you characterize the difference between the later stories and the earlier?

McGrath: Many, though not all, of the later stories are longer and plottier than the early ones, and there are probably a couple of reasons for this. For one thing, there was that ten-year period when he was writing novels almost exclusively, and he had grown comfortable with a looser, more digressive narrative voice. O’Hara, once a famously angry drinker, had also given up alcohol by then. He was more comfortable in his own skin, and it shows a little in the writing, which is more leisurely and expansive. But there are also stories from this period that could easily have been written thirty years before and revisit the tone and the setting—Prohibition-era Gibbsville—of his early collections. They’re a reminder that O’Hara didn’t evolve the way many writers do. He found his voice very early and wisely stuck with it.

LOA: O’Hara had a forty-year relationship with The New Yorker and is considered one of the shapers of the “New Yorker short story.” As a former New Yorker editor yourself, can you explain what’s meant by that? And can a lineage be traced from O’Hara to the two other Johns in the Library of America series, Cheever and Updike?

McGrath: A “New Yorker story,” or its caricature, is one, usually set in some upper middle class home or apartment, in which nothing really happens. In lesser hands it could become formulaic, and by the time I was a fiction editor there, “New Yorker stories” were the last thing we wanted to print. But O’Hara was transformative, and he helped rescue the short story from another kind of formula—the straitjacket of beginning, middle, and end, and often a trick or surprise end at that. In an O’Hara story what happens is most often an internal event—a change in mood or feeling—revealed subtly, sometimes just by implication. It’s not a stretch to compare him to Chekhov.

As far as I know, O’Hara and Updike met only once—it was at the Johnson White House, I think—but they were very aware of each other. Updike grew up reading O’Hara, his fellow Pennsylvanian, and was influenced by him in all sorts of ways. I think O’Hara’s sexual frankness, for example, encouraged Updike to be even more explicit. But perhaps the deepest connection is the way that both writers kept returning to the landscape that had formed them. Olinger is Updike’s Gibbsville.

I don’t know whether Cheever and O’Hara ever met, but it’s not hard to imagine them in a bar together. They had drinking in common, and Cheever, too, was obsessed by social class. Stylistically, Cheever is a little apart from the two other Johns: his Shady Hill is more of a fabulist place than Olinger or Gibbsville. But the quickness and economy of his stories—those are O’Hara traits. The other thing they all share, of course, is a long association with The New Yorker. O’Hara published more stories there than anyone else, and though I haven’t counted, Updike and Cheever might well be Nos. 2 and 3 on the list. They were lucky to have such a reliable, nurturing, and relatively well-paying place to publish, but the magazine was even luckier to have them.