By Carrie Rickey

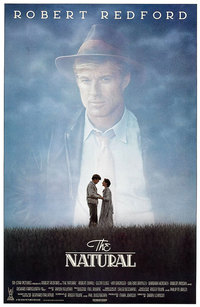

Once reviled, now revered, Barry Levinson’s gorgeous 1984 adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s “midnight-of-the-soul” allegory turns the heraldry, color, and sound of baseball into folk opera.

Bernard Malamud’s The Natural is about Roy Hobbs, a ballplayer whose ambition to “be the best there ever was” gets thwarted at every turn. The book begins with Hobbs in physical darkness, aboard a train in a tunnel on the way to a tryout. It ends with him in existential darkness, effectively having thrown the pennant-winning game—despite second thoughts at trying to win. Barry Levinson’s gorgeous 1984 adaptation opens with the thirty-three-year-old Hobbs, a leathery Robert Redford in the dying spring light, waiting for a train bound for New York where he will report to the Knights as baseball’s oldest rookie. The film briefly flashes back to Hobbs as a boy, playing ball with Dad. It closes with him in a sun-dappled wheat field (matching the amber waves of Redford’s hair) playing catch with a teenage boy.

Upon its release Levinson’s bedtime story based on Malamud’s midnight-of-the-soul allegory met with almost unanimous critical scorn. “Emasculated,” dismissed Pauline Kael. “Vapid,” according to Vincent Canby. “A travesty,” per many others—myself included. How could the filmmakers so keenly observe the particulars of this saga from joyless Malamudville and then make a 180-degree turn to a happy ending?

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| Bernard Malamud: Novels and Stories of the 1940s & 50s |

Despite such drubbing the movie was a modest box office success. Levinson recalls an initial resistance and subsequent embrace of his rookie feature as well. “Diner at first was considered a dark and depressing drama” before it was hailed as a generational comedy, he said in 2016 by phone. With The Natural, he said, “By changing things in a highly-regarded novel, you’re treading on sacred ground.” Sometime between 1984, when the first reviews came out implying Levinson had desecrated the novel, and today, the critical consensus has made the 180-degree turn from revulsion to reverence. Bill Simmons, sports maven and movie lover, contends that “Any ‘Best Sports Movies’ list that doesn’t feature either Hoosiers or The Natural as the No. 1 pick shouldn’t even count.”

The incremental upgrade of The Natural’s critical reputation mirrors the three stages of truth widely attributed to Arthur Schopenhauer. “First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.” Revisiting both book and movie about ten years ago I realized that I’d resisted the power of the Arthurian and crypto-Homeric symbolism that now resonated for me on-screen. Even though the ending was tweaked, as were the endings of book-based movies from Alice Adams to A Clockwork Orange, Levinson, Redford, cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, and composer Randy Newman had found potent cinematic correlatives for Malamud’s literary imagery.

In the novel, when temptress Harriet Bird asks Roy if he’s ever read Homer, the omniscient narrator reports, “Try as he would he could only think of four bases and not a book.” Roy knows from homers, not Homer, is Malamud’s joke. Levinson’s double-entendre is framing the story as an Odyssean journey from home plate, with Roy ducking dangers and temptations before completing his journey back home, literally and metaphorically, to Iris, his patient Penelope, played by Glenn Close.

Robert Redford admired Diner and wanted to work with Levinson. The filmmaker pitched some ideas and the conversation turned to baseball. Redford asked if he had read the Malamud novel. Yes, the director replied, he was a fan. As Levinson recalls, the actor rootled around his office and found the film adaptation of the novel by Roger Towne, brother of Robert (Chinatown), which had interested Michael Douglas and Nick Nolte. Director and actor agreed to go forward. The decision to make the climax more audience-friendly, about second chances rather than second thoughts, was made during preproduction.

Malamud freely mixed mythical metaphors with those of baseball lore: Wonderboy, the bat Roy carves out of a tree felled by lightning, is at once King Arthur’s Excalibur and Shoeless Joe Jackson’s Black Betsy. Harriet Bird, who attempts to murder Roy, is the siren luring Odysseus onto the rocks—as well as Ruth Ann Steinhagen, the celebrity stalker who in real life shot Philadelphia Phillie Eddie Waitkus. Pop Fisher, the Knights manager, is the Fisher King waiting for Percival to restore his kingdom (as in ball club) to fertility (as in hits and wins). If Damn Yankees is baseball’s Faust, The Natural is its Parsifal.

Where Malamud framed baseball as America’s homegrown mythos, Levinson and company reveled in the game’s heraldry, color, and sound by turning it into folk opera. Inspired by American artists such as Edward Hopper and composers such as Aaron Copland, they transformed Malamud’s lamentation into a celebration.

Redford was forty-six when he played the part of Hobbs, thirty-three. Nearly thirty years earlier, the actor had won a baseball scholarship to the University of Colorado and knew the game. He told Levinson that he wanted to suit up as 9, the number worn by Ted Williams. Accordingly, the actor modeled his stance and swing on the Boston Red Sox slugger on whom Malamud, in part, based Hobbs. The actor earned an A for athleticism: “Redford plays so authentically, you want to sign him up,” wrote Roger Angell. More reflective of the damning-with-faint-praise that greeted the film was Wilfrid Sheed’s crack: “Robert Redford’s swing is maybe the best acting he’s ever done.” So sharp was Redford’s muscle memory, remembers Levinson, “That the hardest part of the movie was where he was supposed to strike out and he just couldn’t swing and miss.”

Redford suffers from the prejudice of those who assume good-looking actors don’t need to act. Thus no one talks of the pain etched in the face of his Roy Hobbs, or of that uncharacteristic heaviness with which he carried his upper body, much like one of the slump-shouldered, solitary figures in Edward Hopper paintings.

Hopper seems to have been very much on the mind of Deschanel, whose shadow-ridden compositions suggest both the artist’s atmospheric light and his motif of silhouetting forlorn travelers in railroad cars and hotel lobbies. Malamud writes of Roy, eternal wanderer, that he “hadn’t stopped going wherever he was going because he hadn’t yet arrived.” Deschanel, like Hopper, simplified his palette by subtracting color. And Deschanel, like Hopper and Malamud, achieves the dual effect of realism and magic-realism. It is apt that in this film largely shot at sunset—“magic time,” the cinematographers call it—Deschanel captures Hobbs at career sunset.

Having consorted with his Circe, Memo Paris (Kim Basinger), Hobbs is in a slump. Top of the ninth, and the opposing team is ahead. On deck, Roy seems to hear the notes of a distant trumpet, as though announcing a contestant at a jousting tournament far, far, away. He walks to the plate. Swings and misses. Swings and misses. Iris, backlit in a white hat that circles her head like a halo (in the movie the black and white chapeaus are worn by women), rises to her feet in the stands. Is that a whisper of flutes Roy hears? Comes the third pitch, and—wham! Roy slams the ball over the right field fence into the stadium clock. Randy Newman’s score, interpolating the thunder-crack sound of bats striking balls, swells to orchestral jubilation, the music and mise-en-scene conveying Malamud’s literary imagery: “The clock spattered minutes all over the place and after that the Dodgers never knew what time it was.”

The Natural was only the second movie score for Newman, a renowned singer-songwriter and one in a three-generation dynasty of movie composers. His score for The Natural is not wall-to-wall, cueing the viewer what to feel, but rather an underscoring of select scenes, underlining the superstitions and mysticism of the game and the man. (Fully two-thirds of the film has no score at all.) Like Aaron Copland when he wrote “Fanfare for the Common Man” (to which Newman pays tribute), it is as though the composer has his ear to the ground of America’s rhythms and need only turn up the volume to make them audible to the audience. For a montage of Hobbs’s batting prowess, he composed a passage recalling 1930s swing music. Not only is it appropriate to the time period, but watching Hobbs swing to swing music is a nice audio/visual pun.

As almost everyone knows, in the movie’s penultimate scene the Knights are trailing the Pirates 2-0 in the bottom of the ninth. When Hobbs comes up to the plate there are two outs, runners on first and third. By the time Hobbs reaches a 2-2 count, splotches of blood stain his uniform. With great exertion he smacks a foul ball that splinters Wonderboy in two.

Like Amfortas in Wagner’s Parsifal, Hobbs has a wound that will not heal. The wound can be healed by the saber of a pure youth, such as Parsifal. Hobbs’s Parsifal is the batboy who picks him a replacement stick, the bat Hobbs has helped him make. Hobbs smacks the next pitch out of the park and into the lights, showering sparks on the team and winning the grail of the pennant.

William Dean Howells famously remarked, “What the American public wants is a tragedy with a happy ending.” In his version of The Natural, Levinson made that a good thing—and ultimately, Malamud agreed with him. This son of Jewish immigrants and serial portraitist of social outsiders frequently got lumped with Saul Bellow and Philip Roth as “Jewish novelists.” According to his daughter, Janna Malamud Smith, when the author left the movie theater after seeing The Natural, he turned to his wife and said, “Now I’m an American writer.”

The Natural (1984). Directed by Barry Levinson. Written by Roger Towne and Phil Dusenberry, from Bernard Malamud’s novel. With Robert Redford, Glenn Close, Barbara Hershey, Kim Basinger and Wilford Brimley.

Buy the Blu-Ray • Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Carrie Rickey, longtime film critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer, writes for many publications, including Yahoo! Movies and The New York Times, on subjects related to film. Essays of hers are collected in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll and the Library of America anthology American Movie Critics.

The Moviegoer, a biweekly feature from Library of America, showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.