Our series of guest blog posts by contemporary writers returns today with a contribution from Leopoldine Core, whose debut story collection When Watched has just been published by Penguin Books.

The Village Voice has characterized the stories in When Watched as “domestic dramas that read like miniature plays perceived through a keyhole,” adding, “What makes [Core’s] writing so captivating, ultimately, is her ability to levitate seemingly mundane experiences with the sheer intensity of her attention.” The Los Angeles Review of Books noted enthusiastically, “one gets an otherworldly sensation from Core’s writing,” and Sheila Heti has called Core “one of the most original new writers I’ve come across.”

In the guest post below, Core offers some thoughts on three books that have influenced her writing.

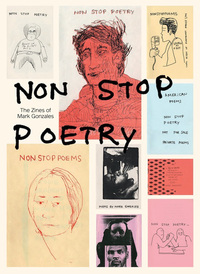

Mark Gonzales, Non Stop Poetry: The Zines of Mark Gonzales. The poems of Mark Gonzales speak to the distracted part of me—they are, in a way, distraction itself. Skinny stacks of moments, glances at a life, jokes careening into dead seriousness.

ARE YOU

TRYING

TO RUiN

MY

CARREAR

IS WHAT

A DRUNK

TOLD A 711

ENPLOYEE

WHEN HE

TOLD HIM HE

WAS CRAZY

HE THEN LEFT

THE STORE NOT

PURCHISING A THING

I groan at the look of this poem typed up—the soul of it is somewhat diminished. And it is Mark’s soul that I’m drawn to. His poems don’t belong in a Word document on a computer—they’re drawings. They live on the page in his distinctive handwriting, mostly caps, with misspelled words blazing throughout, except that they don’t look misspelled, they look exactly right. But more than that, they feel right—they tweak my experience of time in a pleasurable way.

Helplessly I hover over the word “CARREAR”—it glows, protracting the moment. I see the words “CAR,” “EAR,” and “REAR.” Is that what a career contains? A car and ears and an ass? Sure. Yeah. Maybe. His poems are holographic in that they change in their meaning depending on where you are standing.

Maybe I see a joke where there isn’t one, or maybe I ought to laugh but do not. And I don’t mind—these poems seem to welcome my bent reading. Mark is an inventor and he prompts us as readers to invent. The poems go in easily and once inside, they persist—you can’t un-know this voice. We are as moved by the words as we are by the shapes they take on the page—indeed, the two are inextricable. His poems encapsulate the basic truth that meaning and form can’t be yanked apart—they straddle each other always.

Jenny Zhang, Hags. Some pieces of writing are perfect—this one is. Hags is a varied, trembling creature of a book. It’s a personal essay but it is also a journalistic endeavor and it is also a short story and it is definitely a poem. To be alone with Zhang’s thoughts is a gift—I want to call her inimitable but I kind of hate that word. Anyone can be imitated and most geniuses are. It’s beside the point. She’s brilliant—that’s the point.

Whenever I start to describe Zhang’s work to someone I switch gears in the middle of a sentence, saying some new thing that might contradict the thing I just said. Her voice is impossible to pin down and the work kind of pinches you when you try. And yet it is also a voice that we come to know deeply—her way of delivering truth at the end of a very long sentence, her perversity that reads like sanity itself, her funniness, her incredible heart, her way of cultivating a dual intimacy—a two-way mirror that means we don’t just see her thoughts, she sees ours. Zhang sees America, finally, and the problem of living inside it, how the self keeps spilling out of this awful little cup.

The effect of Hags is kinesthetic, it gets in the room and in your blood, and then you think you know Zhang and she proves you wrong. And I’m having this idea right now that love is built out of the sensation of being proven wrong. I love when a voice shoves me into my awe by saying no, look over here instead—look at this now. Hags orders us to LOOK, LOOK, LOOK and greedily, we obey. I love this little green book. I love its mind.

Nella Larsen, Passing. I remember, reading Passing in college, how everyone in my class seemed to wake up. My teacher explained that the book explored both racial and sexual ambiguities—“It’s a queer text,” he commented. And so I read with the book an inch from my face, ravenous for the queer sex that I imagined would occur—but did not. And in this way, the book delighted me. I experienced Passing as a tantric text, in that it pointed out my desire.

I became obsessed with so many sentences, reading them again and again, high on the subtext. It seemed to me suddenly that some of the queerest books were the ones that didn’t name themselves as such. They had an aura instead. And I felt a license suddenly not to label the sexuality of my characters. I could identify them instead through their behaviors, the evidence of their obsessions—and through their voices, the things they said and could not say, from moment to moment.

Larsen broadened my sense of what was possible in a third-person narrative, because she made me question my mind as I read. Her omissions had the effect of heating the text—what I knew was just as crucial as what I did not know, or did not see, or mis-saw. Passing, first published in 1929, is a radical work. It forces the reader to perceive race and sexuality within a spectrum—thus underlining the illness of a society that, to this day, denies the existence of this spectrum.

Hunter College graduate Leopoldine Core received a Whiting Award for fiction in 2015, and has also won fellowships from The Center for Fiction and The Fine Arts Work Center. Her writing has appeared in Joyland, Open City, PEN America, and Apology Magazine, among other outlets, and her debut poetry collection, Veronica Bench, was published by Coconut Books in 2015.