By Stuart Klawans

The veteran director’s rare fidelity to both the surface and the unspoken depths of Flannery O’Connor’s novel allows him to preserve the essential mystery of its protagonist, Hazel Motes.

Flannery O’Connor’s first novel, Wise Blood, presents an almost irresistible temptation for a movie director, and an almost insurmountable challenge to go with it. Vivid (if not lurid) action and indelible characters tantalize the imagination, only to lose their sense as soon as you think of how to translate them to the screen. Strip away the language of O’Connor’s narration, with its web of symbolism and indirect discourse, and the story’s meaning vanishes. So the director hoping to film Wise Blood would seem to have three choices: drowning the picture under voiceover narration, forgetting the narration and simply re-enacting the story (which would then risk becoming little more than a freak show) or giving up.

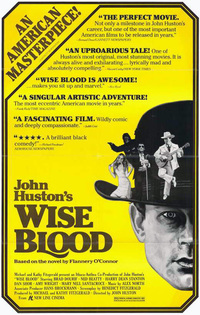

In his 1979 version of Wise Blood, John Huston finds a fourth way. Rejecting voiceover narration, he puts his behavioralist approach to character and classically direct visual style at the novel’s service and in the end achieves fidelity to the surface and to the unspoken depths, too. His faithfulness to the source goes beyond keeping O’Connor’s plot and dialogue remarkably intact. More crucially, he remains faithful to the “mystery” (as O’Connor called it) of the protagonist, Hazel Motes. Huston hints at the merit of the man’s inner struggle while viewing his desperate, driven, outlandish, and horrifyingly funny career strictly from the outside.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| Flannery O’Connor: Collected Works |

Huston introduces Haze the way O’Connor does: as an uprooted man, discharged from the Army after wartime experiences that have left him indefinably scarred. In an elegiac prologue, the only leisurely and tender section of the movie, you see that Haze’s town in rural Tennessee is depopulated, his family deceased, his farmhouse a looted ruin. With no home and no firm idea except that everything he’d believed must have been a lie, Haze takes off for the city, determined “to do some things I never have done before.” He doesn’t seem to have thought much about what those things ought to be, other than affronts to the morals he inherited from his circuit-riding, Jesus-shouting grandfather. Fornication with a prostitute will do for a start.

But then, provoked by an encounter with an “evil-seeming” blind street-corner preacher, Asa Hawks, and his young daughter Sabbath, Haze testifies publicly to his lack of faith. Impromptu, he claims to have established the Church Without Christ. Until this point, people have repeatedly taken Haze for a preacher because of his fierce stare and severe black hat. Now he becomes a preacher—a sincere one, too, unlike Hawks—who speaks with burning conviction against the Jesus his grandfather had professed. All the other characters are indifferent to Jesus, but Haze has the merit of denouncing him, hating him, trying to flee from him, while never being able to shut him away.

Haze’s tormenting bond with Jesus is the difference between him and his foil, Enoch Emery, a similarly young, ignorant, and friendless newcomer to the city. Haze distrusts the promptings of his flesh (while indulging them almost programmatically), cares only for the pursuit of truth (while furiously denying the truth that’s most innate and insistent to him), and cannot permit his own mind, or anybody’s, to idle in the bed of unexamined assumptions. He’s always boiling over with words and ideas, many of them overwrought, offensive, odd or (when it comes to his car) delusional—and this makes him the worthy but self-doomed hero of a film based on a novel that O’Connor called hopeful and full of zest.

Blink, and you might miss the point.

Like O’Connor, Huston keeps his distance while observing Haze. But whereas O’Connor never stoops to explaining the character, she does suggest the integrity at his core by contrasting his fervor with the prevailing atmosphere of blindness, brutishness, and empty gentility. She surrounds Haze with objects that she describes as disturbingly bright, from his “glaring” blue suit to the “glare” of shop windows and movie marquees. She also elevates his crankiness (the intellectualism of the unsophisticated) by contrasting it with the meanness of the other characters, revealed by an indirect discourse that she uses to penetrate their minds but never Haze’s.

Here, for example, is Haze’s landlady, Mrs. Flood:

She felt that the money she paid out in taxes returned to all the worthless pockets in the world, that the government not only sent it to foreign niggers and a-rabs, but wasted it at home on blind fools and on every idiot who could sign his name on a card. She felt justified in getting any of it back that she could. She felt justified in getting anything at all back that she could, money or anything else, as if she had once owned the earth and been dispossessed of it.

Mrs. Flood’s feelings attach to no incident or even period in her life. They float free in time, much as the point of view hovers between the observer and the subject, in language that doesn’t settle inside or outside the character but instead merges a cool omniscience with Mrs. Flood’s harsh diction and obsessive cadences. O’Connor has a character’s opinions to report, but she doesn’t place you at the level of a mind formulating anything so grand as ideas, or even thoughts. Instead, she takes you to their substratum: the poisonous mulch from which Mrs. Flood sprouts her resentments.

Consider, too, the resentments of Enoch Emery, whose pre-verbal impulses (which he honors as a form of knowledge) give the novel its title. Enoch also nurses a sense of being cheated. Unlike Mrs. Flood, he cannot even begin to articulate his grievances, but he feels them every time he looks at the animals in the zoo, where he works as a guard:

The cages were electrically heated in the winter and air-conditioned in the summer and there were six men hired to wait on the animals and feed them T-bone steaks. The animals didn’t do anything but lie around. Enoch watched them every day, full of awe and hate.

O’Connor’s language brings you into Enoch’s way of thinking, planting the idea that he lives like an animal, having faith only in the corporeal judgments of his “wise blood.” In a similar way, O’Connor later describes how Mrs. Flood, in her cupidity, senses something “valuable” might be hidden near her—something she wants to grab, while irritably suspecting it’s been secreted behind Haze’s now sightless eyes.

Huston must abandon this level of the book. To suggest in words how Jesus tugs at Haze, the movie retains nothing from the text except three outbursts—you can’t really call them dialogue, given the way the characters talk past one another.

Asa Hawks to Haze: “Some preacher has left his mark on you. Did you follow for me to take it off or give you another one?”

Haze to Asa Hawks: “What kind of a preacher are you, not to see if you can save my soul?”

Sabbath Hawks to Haze: “I seen you wouldn’t never have no fun or let anybody else because you didn’t want nothing but Jesus!”

Viewers who come fresh to the movie and don’t pay attention to these lines may take the movie’s Hazel Motes at his word when he rails against Jesus. Huston ushers you into Haze’s mind only in a few rose-tinted flashbacks that establish psychological trauma rather than spiritual fixation. The direction allows cynics the liberty to interpret Haze’s preaching as an unpolished mirror of their own disbelief.

Huston also leaves secularists free to join with Mrs. Flood in thinking that Haze, in his late penance, is backward and perverse. After all, he is. Like many of O’Connor’s characters, Haze is little more than functionally literate and almost untouched by the world of ideas. This is part of what makes him funny. So a viewer may give in to prejudice and think of the movie as a joke on the South as a whole, imagined as a region of the barely schooled and extravagantly superstitious. Huston’s one serious lapse encourages this condescension: he underscores Enoch Emery’s escapades with jocular music of the hee-haw variety. I doubt O’Connor would have enjoyed it. But in his overall treatment of the setting, Huston strikes a note that O’Connor might have approved, even though it begins with an act of infidelity to her text.

Huston updates the novel. You see that at once from the interstate highways, the style of the cars, and the outcroppings of a few concrete-and-glass buildings. O’Connor’s late 1940s have been left behind. The period is now the early 1970s—the recent past, relative to the movie’s release in 1979—and Haze must be a veteran of Vietnam, rather than World War II. At the same time, though, Huston grandly ignores the New South—that recently moneyed region of office parks, Marriott hotels, and the occasional black mayor—that rose to world attention with the election of Jimmy Carter. The great majority of his locations look as if they had already been antique in the 1940s, and most of the people behave as if the Civil Rights movement had never begun. The train that carries Haze to the city is coal-fired, not diesel, and the most thrilling attraction at the neighborhood movie theater (in the era of Spielberg’s shark) is still a man in a gorilla suit.

Huston’s new yet unchanged setting provides a correlative to the steady yet wavering vision of O’Connor’s indirect discourse, and the timeless abjection it reveals beneath the transitory details of her characters’ lives. Think back to Mrs. Flood, who belongs to the middling cities of late ’40s Georgia, as bark to a tree. She’s alive where O’Connor fastens her and wouldn’t be if you stripped her away. And yet O’Connor exposes attitudes in Mrs. Flood that seem independent of time and place. (Mrs. Flood is hardly alone in feeling as if she had once owned the earth and been dispossessed of it. Many voters, not only in the South, have the same notion in 2016.) Huston allows himself no recourse to the inner thoughts, or proto-thoughts, of his characters. But his treatment of the setting enables him to revel in credible local color while at the same time sliding beneath it, to a more enduring level.

He also fully exploits another resource that is at once transitory and absolute: the singularity of his actors, who belong to the imaginary time of the story but also transcend it, as never-changing facts fixed forever in celluloid. The abiding specificity of the actor is the bedrock of classic moviemaking as practiced by Huston throughout his career. To quote an old Hollywood adage that has frequently been attributed to Huston, ninety percent of a director’s job is casting. In Wise Blood, he could hardly have directed any better.

He found Hazel Motes in Brad Dourif, who had made a strong impression in his first notable film, Milos Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), and was still fairly new to the screen. Nothing he had done before was likely to distract the audience from his embodiment of Hazel Motes; nothing he’s done since, in a prolific career, has so defined him as an actor. Every part of Dourif in Wise Blood is sharp and spare—his nose, his chin, the bones that poke from his torso—except for the clear eyes, wide and slightly protuberant, that don’t so much take in the world as beam emotions out to it. Dourif’s Haze is frailty and menace in one package. When he speaks through gritted teeth (as he often does) or propels himself along a sidewalk, his shoulders akilter and his jaw pushing ahead, you see a man who is sternly, furiously blind to anything that doesn’t match the pictures in his head.

Huston’s choice to play Enoch Emery, Dan Shor, was entirely new to the movies. Unlike the book’s Enoch, he is not physically repulsive—if anything, Shor is boyishly cute—and the movie does not burden him with his literary counterpart’s creepy compulsions. But when you see him carrying on with Dourif in a long, long tracking shot—a yappy, shaggy-haired, oval-faced puppy, bouncing in little arcs next to its terse, inattentive, and relentlessly linear master—you have an ideal foil for Haze’s unswerving inner direction.

The other character whom Haze talks past in long two-shots is Sabbath Hawks, played by Amy Wright, an actress who had become familiar in ingenue roles by 1979. She does not look like a “child,” as the novel describes Sabbath. (“Would you guess me to be fifteen years old?” the book’s Sabbath asks Haze with would-be seductiveness, allowing the reader to understand that she’s not yet close to the age of consent.) Even today, another forty years past the demise of the Production Code, there are realities that a director cannot get away with representing. But in Wright’s light soprano (which she makes alternately flat and dreamy), smooth oval face, and air of reluctant tomboyishness, her body tamped down under a knit watch cap, Huston gets a very close approximation to Sabbath’s juvenile dirty-mindedness.

As for the “evil-seeming” Asa Hawks and the unctuously “winning” street-corner preacher Onnie Jay Holy, what more could Huston want than Harry Dean Stanton and Ned Beatty? The two men might as well not be actors at all, but found objects collaged into the frame.

Wise Blood sticks exceptionally close to the incidents and dialogue of its source. Its great faithfulness to O’Connor lies elsewhere, though: in the actors’ tactile realization of her characters, in the uncanny sense of being in a place that exists both in real time and outside of it, and in Huston’s determination to preserve the inexplicable mystery of Hazel Motes.

As O’Connor wrote in her preface to the tenth-anniversary edition, a novel, even a comic one, may deepen our sense of how unfathomable are the uses to which people put their freedom. A comic movie may do the same. At the end of the film, Huston doesn’t provide O’Connor’s narration of the confused, mean-spirited, yet apt intuitions of Mrs. Flood to prompt your feelings about Haze. All Huston gives you is Brad Dourif—his newly subdued voice, his hunched posture and tentative gait—and it’s enough. When he sets forth again, you see a man who has successfully put himself beyond anything trivial, including the mockery of others. That’s faith—and that’s faithfulness to Wise Blood.

Original 1979 trailer for Wise Blood (2:24)

Wise Blood (1979). Directed by John Huston. Written by Michael and Benedict Fitzgerald, based on Flannery O’Connor’s novel. With Brad Dourif, Amy Wright, Harry Dean Stanton, Ned Beatty, and Dan Shor.

Buy the Criterion Collection DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes

Stuart Klawans has been the film critic of The Nation since 1988. He has written about films and literature for publications including The New York Times, TLS, Grand Street, Parnassus: Poetry in Review, and Film Comment. His book Film Follies: The Cinema Out of Order was a finalist in the criticism category of the National Book Critics Circle Awards.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.