By Wendy Lesser

Stunning visual beauty and “the conviction of a dream” distinguish this 1960 adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s paranoid suspense classic.

Turning one of Patricia Highsmith’s marvelous Ripley novels into a film is a mug’s game. The mood of her free indirect narration—anxiety-producing, paranoid, and always reflecting Tom Ripley’s intelligent but not-too-stable perspective—is impossible to reproduce in a movie, not only because it is essentially linguistic in texture, but also because it allows the novel to float disconcertingly in the space between Ripley’s mind and the outside world. And without this delicate verbal tether joining us to Tom symbiotically, as it were, we are left uncertain of our relation to him. Any directorial efforts to create sympathy for this murderous central character risk tilting the whole enterprise over into Grand Guignol farce, while any attempts to distance us from him are likely to yield boredom and distaste. The filmmaker has to be extremely inventive to get around this dilemma, but here’s the catch: the more inventive he is, the further he is bound to travel from the initial point of attraction, Highsmith’s Ripley.

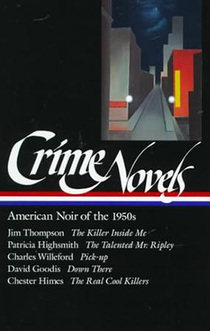

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1950s |

The best Ripley movies I’ve seen are Wim Wenders’ The American Friend (1977) and Liliana Cavani’s Ripley’s Game (2002). The former succeeds by becoming something entirely other: when I first saw it, I didn’t even realize it was a Ripley movie, so wholly does the Bruno Ganz character, Timmerman, take over from Dennis Hopper’s Ripley. The latter succeeds by casting John Malkovich in the languidly malicious Ripley role—an inspired match-up that leaves us rooting for the villainous hero even as we despise ourselves for doing so. Both films have the enormous advantage of being based on a late novel in the series, Ripley’s Game (1974), which shows Tom already ensconced in his comfortably well-off life as an art collector living in the French countryside. Murder, in these circumstances, is an old ploy he uses to keep himself safe, not a newly discovered method for self-elevation.

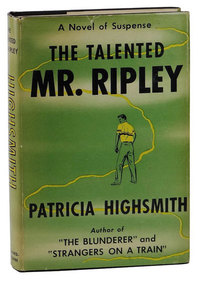

It is far riskier to take on the series’ first novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), because here we actually see Tom turning from a relatively harmless perpetrator of forgery and mail fraud into a successful murderer-for-gain. The 1999 Anthony Minghella film of that title, for example, was a complete failure—in part because it hewed too cravenly to the Highsmith plot, and in much larger part because it inexplicably cast the bland, square-cut, toothy Matt Damon in the quicksilver role of Ripley. But a much better film of the same novel, though also a much weirder one, was made by René Clément in 1960, only five years after Highsmith first introduced her character in print.

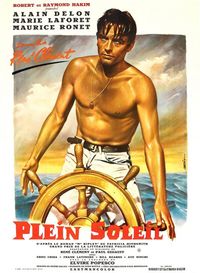

The film’s title (Plein soleil, or “full sun,” in French) has been rendered as Purple Noon in English, for reasons that utterly escape me—but no matter. Rationality, or even irrationality, is not the point here. The movie has the conviction of a dream in which everything that happens seems both necessary and unprepared for. Cleverly understanding that his only source of superiority over Highsmith lies in film’s visual quality, Clément has made his movie incredibly lovely, and in fact has employed this loveliness to detach us from our usual moral foundations. The characters are beautiful, so we find ourselves helplessly drawn to them, and then to their delightful environments and opulent possessions—we can’t help but feel how nice it would be to be surrounded by such things. Hence the central features of Ripley’s personality—his wish to be someone other than he is, and his desire to possess more than he does—have been displaced onto us, relocated into us, without our even being fully aware of the process. At the same time, we remain sufficiently apart from him to notice the moments at which he is losing his own identity and turning into Greenleaf, the person he will eventually kill.

The gorgeous cinematography (beginning with a credit sequence in which a recognizable Rome, seen from above, appears dipped in a series of intense colors) is only one aspect of the filmic beauty. Equally important is the casting: the luscious Alain Delon as Ripley, the hunky Maurice Ronet as Greenleaf, and even the seductive Marie Laforêt as Marge—the sole female character of note, who in Highsmith’s version is merely a gourd-shaped loudmouth aspiring to be Greenleaf’s steady girlfriend. Minghella, too, felt unable to leave Marge as a Plain Jane (he cast Gwyneth Paltrow in the role), but because he was trying to be faithful to the novel, he didn’t quite know what to do with this uselessly pretty girl. Clément makes her essential to the plot, not only as the witness to Greenleaf’s profound humiliation of Ripley—she watches uncomfortably as he ridicules Tom’s manners and clothing and speech—but also as the reassigned love-interest through whom Ripley plans to get hold of Greenleaf’s fortune. In a twist that goes far beyond anything in the novel, Delon’s Ripley forges a suicide note from the vanished Greenleaf, then forges a will leaving everything to Marge, who has already begun to transfer her wounded affections to Tom. It is all very French (and very unlike Highsmith).

Still, even as he pursues this pseudo-romantic, victimized-murderer line, Clément retains his grasp on one of the novel’s basic elements: wishful identification merging into homo-eroticism. The scenes between Delon and Ronet, often in alternating close-up, emphasize the ways in which these actors resemble each other. And even when the two men are at their most antagonistic—discussing aloud why Ripley might want to kill Greenleaf, for instance—they are collusive and intimate, purposely keeping their conversation hidden from Marge.

The extreme Frenchness of the movie does cause a few road-bumps. The supposedly American Greenleaf (who has been renamed from “Dickie” to “Philippe,” presumably to make him less ridiculous to the French ear) is too aristocratic, too concerned with proper table manners, too disdainful of Ripley’s poverty—and though this gives Tom additional motives for murder, it also makes Greenleaf seem like the kind of unconscious snob who would only appear in a French film. In fact, all the main characters are supposed to be Americans, and poor fat Freddie (Ripley’s second victim) obviously is American, with his atrocious French accent and his “So long, chum,” so why don’t we get to hear or see that nationality in anyone else? The story, in Highsmith’s hands, is crucially about an American sent abroad, a former naif who has his eyes opened and his desires aroused by the encounter with Europe. (She even invokes Henry James’s The Ambassadors explicitly, though with the kind of fleeting lightness that only a complete mistress of her craft could manage.) All this is lost if the characters are self-evidently French.

But logic, or even persuasive cultural history, is not what Clément is going for here. He has zeroed in on Ripley’s capacity for generating suspenseful paranoia, his appeal to us as a hunted man. While retaining throughout a certain amount of Tom Ripley-ish detachment, we repeatedly fear for him and with him, breathlessly squirming through the dicey moments, dreading the encounters with cops, hoping against our better nature that he will get away with it all. In this respect the director has remained utterly true to his source.

Until the very final scenes of the movie. (And here you really must stop reading if you haven’t seen the film yet.) The fact is, I simply can’t forgive Clément for allowing Ripley to be captured and exposed at the end. An unsuccessful Ripley, a Ripley who does not get away, is not a Ripley at all, for the whole point of the series is that his pathological method works: he enriches himself and goes on to kill as needed, blithely fooling all the police and private detectives thrown in his path. To violate this aspect of Ripley—to cave in to all the petty little legalities and moralities contending for our detective-fiction souls—is to betray both the novel and its author at the deepest level, and that is finally unacceptable for a Highsmith-lover like myself, however beautiful, intelligent, and charming the rest of the movie is.

Purple Noon (1960). Directed by René Clément. Written by Clément and Paul Gegauff from Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley. With Alain Delon, Maurice Ronet, and Marie Laforêt.

Buy the Criterion Collection DVD • Buy the Criterion Collection Blu-ray

Watch on Amazon Video

Wendy Lesser, the founding editor of The Threepenny Review, is the author of ten books, including The Amateur, Pictures at an Execution, and Why I Read.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.