This September, Library of America inaugurates its edition of Ursula K. Le Guin with The Complete Orsinia, the first comprehensive collection of Le Guin’s historical fiction set in the imaginary central European nation of Orsinia. In the following guest post, the book’s editor, Brian Attebery, suggests how the Orsinian tales can be understood in relation to Le Guin’s larger body of work and uncovers some relatively little-known literary antecedents.

By Brian Attebery

Ursula K. Le Guin has found many narrative routes into what she called, in accepting the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, “a larger reality.” Best known for science fiction and fantasy, she has also written utopias and dystopias, magical realism, mock scientific papers, invented or subverted folktales, alternative histories (it didn’t happen but could have), crypto-histories (maybe it did happen but you just didn’t notice), and a tightly poetic form she calls “psychomyth.” Each of these frameworks serves to make the familiar strange: to cast doubt on common sense and thus to make readers question assumptions about society, identity, and justice. They are what she has called “distancing mechanisms,” but the distance is functional. Le Guin wants to move the earth. To do so she needs narrative levers like fantasy, but also places to stand.

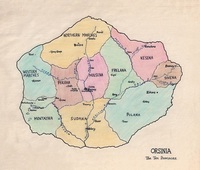

The first standing place she found, before the planet Winter or the magical realm of Earthsea, was a country called Orsinia. Orsinia is somewhere in central Europe, part of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. The furthest thing possible from the vaguely-located comic-opera kingdoms of Anthony Hope, George Barr McCutcheon, or—in Duck Soup’s Fredonia—the Marx Brothers, Orsinia feels solid. It has geology—rivers, mountains, a limestone plain—and institutions like the church and the barely tolerated press. Like Romanians, Orsinians speak a Romance language influenced by Slavic neighbors. It has both a folk literature and an elite one.

Above all, it has history, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say it endures history. Le Guin’s poems and stories about Orsinia (which I’ve been annotating for the new Library of America edition of The Complete Orsinia) reflect the strivings and sufferings of its people as they seek freedom and are repeatedly and brutally suppressed.

But Orsinia does not exist, any more than Middle Earth exists. It isn’t real, though its troubles are. One of the problems it poses is to figure out what kind of lever spans the gap between the imaginary place and the earth that is to be moved: in other words, what genre are we dealing with?

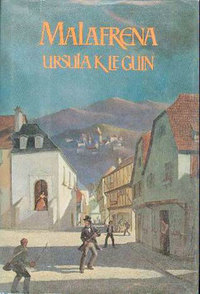

The clearest clue is Le Guin’s acknowledgment of a literary ancestor: Austin Tappan Wright, whose novel Islandia was published posthumously in 1942. She has written repeatedly of her admiration for the book’s sweep and detail, and calls it “a genuinely alternative society, worked out thoroughly, pragmatically, and humanely. And it is a novel. It is full of real people.” Like Le Guin’s Malafrena, the novel is set in an imaginary country (on an invented continent in the Southern hemisphere) with a real history, which is to say, a believable human history. It has no magic. Its citizens interact with people from Europe and America. It has its own detailed geography, economy, customs, clans. Neither utopian nor dystopian, it is, as Le Guin says, alternative.

Whatever Orsinia is, it is not alone: if two novels and a scattering of shorter texts constitute a genre, Malafrena and the other Orsinian tales belong in one with Islandia. Since genres are, among other things, instructions for reading, it’s helpful to look at what both Wright’s imaginary society and Le Guin’s—and the stories that bring them to life—have to say about their own nature, internal dynamics, and meanings.

An orientation to the story-world of Orsinia can start from the word “alternative,” which suggests difference, distance, otherness, and options. Alternative beliefs challenge orthodoxy. Alternative lifestyles de-naturalize social norms. Alternative societies can be utopian and dystopian at once, like the cooperatively anarchist world of Le Guin’s science fiction novel The Dispossessed, subtitled “An Ambiguous Utopia.” And alternatives alternate—as readers find themselves alternating between the fictional world and the world of experience. Each Orsinian story flickers between its own historical present and the reader’s own moment, which it alternately illuminates and critiques.

And that is how the earth, our earth, is to be moved. I’ve been lucky enough to be friends with Ursula K. Le Guin for almost forty years, and I have seen her commitment to fairness and the long view. She cares deeply about silenced people and neglected landscapes (such as the Eastern Oregon desert recently despoiled by the short-sighted and selfish occupiers of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge). She is interested in revolutions of all sorts: social, political, cognitive. The Dispossessed is about a revolution that succeeds; Malafrena about one that fails but leaves behind it swirling fragments of hope and resentment that periodically try to coalesce into another, more positive transformation. In the last of the Orsinian stories, the breathtaking “Unlocking the Air,” they seem to have done so at last. Both the tragic and the hopeful outcomes of Orsinian rebellions throw our own troubles into relief: ours are first-world problems, as opposed not to the third world (as the saying is usually applied) but to the second, the eastern countries that never quite prospered or broke free from tyrannies of right or left.

By speaking from Orsinia, as its only authorized emissary, Le Guin reminds us of everything we take for granted and everything we have neglected. In the 1890s, Mark Twain’s friend William Dean Howells published A Traveler from Altruria. As the title suggests, the structure of the book is unusual for utopian fiction: we never get to Altruria but we do get to see Gilded Age America through the eyes of the titular traveler, who is shocked by the inequity and greed that Americans see as inevitable. His otherness, his alterity (suggested in the name of his country), makes the invisible visible and challenges his hosts to do better.

Our visitor from Orsinia does the same. From the first “Folk Song from the Montayna Province” (published in 1959) to the quasi-nineteenth-century novel (which is also a metafiction about nineteenth-century novels) to the varied and elegant short stories about Orsinia’s past and present, the emissary has provided us with alternatives aplenty. She shows us how oppression disguises itself as security and how ideas nevertheless sneak across borders. She reminds us of the power of art (especially music) to console but also to disrupt order and transcend limits. She asks us to look more carefully at the conditions of our lives and to stop assuming they are inevitable. She has given readers the lever and the place to stand. Moving the earth is our job.

Brian Attebery is professor of English at Idaho State University and the editor of