By Gene Seymour

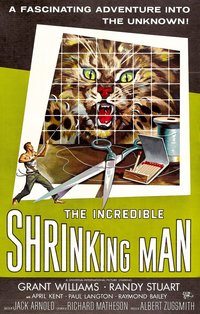

Commonplace settings and objects are freighted with an almost otherworldly menace in this ingenious adaptation of Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel, which benefits enormously from director Jack Arnold’s respect for genre and “no-nonsense craftiness.”

The whole thing began with Aldo Ray’s hat.

No, Aldo Ray wasn’t in 1957’s The Incredible Shrinking Man, even though he seemed to be in every other movie made around that time. But there wouldn’t have been an Incredible Shrinking Man without his hat being too big for Ray Milland’s head during an otherwise insignificant 1953 romantic farce called Let’s Do It Again, in which Jane Wyman gets back at her philandering composer-husband, played by Milland, by having an affair with a uranium millionaire, played by Ray.

As Shrinking Man’s creator, Richard Matheson, relates in Stephen King’s invaluable critical history of horror fiction, Danse Macabre, “Milland, leaving Jane’s apartment in a huff, accidentally put on Aldo Ray’s hat, which sank down around his ears. Something in me asked, ‘What would happen if a man put on a hat which he knew was his and the same thing happened?’” Matheson, a science fiction writer, saw this “silly comedy” in a Redondo Beach theater. From that oversized hat, he teased out a far more somber tale of an average middle-class male named Scott Carey who, after a double whammy of being exposed to a radioactive cloud after ingesting pesticide, finds his whole body getting too small for his clothes, his house, his cat, and everything and everyone he’s ever known.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in American Science Fiction: Four Classic Novels 1953–1956 |

Matheson (1926–2013) had by then become a leading voice in the burgeoning West Coast–based community of postwar science fiction and fantasy writers who, in Peter Straub’s words, “perfected a clean, craftsmanly sub-genre that could be called California Gothic [and whose] stories were as carefully engineered as haikus and as intolerant of wasted motion.” By decade’s end, Matheson would be a steady contributor of scripts to The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling’s landmark TV series of homespun but indelibly dark phantasmagorias. Remember Agnes Moorehead alone at night on a farm battling tiny spacemen who emerge from a tiny saucer? Matheson wrote that 1961 episode. During one inspired stretch, Moorehead’s kitchen knives are used against her. This notion of malign forces both mundane and exotic surrounding a solitary person is at the core of Matheson’s work in general and The Shrinking Man in particular.

Starting in late 1954, Matheson spent two-and-a-half months writing this novel in interwoven vignettes that flow like cinema. As he shrinks, Scott is besieged by all manner of humiliation and dread, coalescing into an all-American Cold War-era Kafka-esque nightmare for the drugstore racks, complete with bullies, child molesters, and a spider assaulting his dignity, and, finally, his very life.

Matheson worked on Shrinking Man in the basement of a rented house in Sound Beach, Long Island. In a letter to one of his favorite professors from his University of Missouri alma mater, he considered the book to be “the best thing I’ve ever done to date.” The environment was apparently so conducive to his writing that it was absorbed into his story. “I didn’t alter the cellar at all,” he later recalled. “There was a rocking chair down there and, every morning, I would go down into the cellar with my pad and pencil and I would imagine what my hero was up to that day. I didn’t have to keep the environment in my mind or keep notes. I had it all there, frozen.” (When Matheson watched the movie version being shot, he was “taken aback” by how much that basement resembled the one depicted in the film, where tiny Scott finds himself hopelessly trapped among tools and furniture too big to use.)

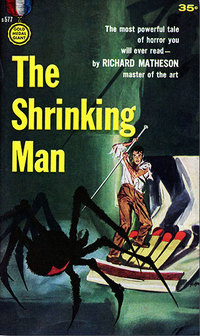

Soon after its initial publication as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback, Universal Pictures bought The Shrinking Man. “I don’t expect anything to come of it,” Matheson wrote to his professor. “I’m afraid it would be much too difficult to make into a movie—unless, of course, they hoked it up as they usually do.” Adding the word “Incredible” to Matheson’s original title may have been a portent of studio “hokey-ness” to come, though Matheson seemed to take the adjustment in stride. What else could one do during the so-called “Fabulous Fifties,” when drive-ins from coast to coast were hyping movies with such blaring, lurid titles as The Beast with a Million Eyes, Creature with the Atom Brain, It Came from Beneath the Sea, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, and the relatively-simple-but-still-somehow-ominous Them?

Yet even in this gaudy company, The Incredible Shrinking Man stands out as one of the more ingenious, unsettling, and durable movies of its kind. At once elaborately designed and structurally austere, the movie, as with the greatest in its genre (whether you use Vampyr or Night of the Living Dead as a touchstone), feels like an improbable dream that oozes into your waking consciousness and seems somehow more “real” than any number of grittier, down-to-Earth melodramas. Even Pauline Kael, a tough audience for such fare, praised the film for having “more consistency and logic than usual.”

As cinematic nightmares go, it’s relatively subdued in tone, owing in large part to Matheson’s screenplay, which exemplifies his dry, clean style. And the film was fortunate in its director, Jack Arnold (1916–1992), whose body of work was mostly well crafted and unassuming—though it includes that anomalously greasy slice of oddball cool, 1958’s High School Confidential, where such rogue elements as beat-poet delinquents, deep-cover drug agents, Mamie Van Doren, and Jerry Lee Lewis somehow meld into a barely plausible yet enduringly captivating artifact. But science fiction, especially the “what-if” subgenre of monstrous distortions in natural things, always brought sharper focus to Arnold’s uncluttered, unhurried approach. From 1953’s It Came From Outer Space to 1958’s Monster on the Campus, with such glow-in-the-dark chestnuts as 1954’s Creature from the Black Lagoon and 1955’s Tarantula in between, Arnold treated the genre with respect (apparently, he was a fan of it as a kid) while displaying a no-nonsense craftiness with atmosphere, narrative drive, and tone, all in beautiful black-and-white. The movie retains the episodic flow of the book, its revelations seeping through the narrative with a crisp, measured pace.

In the title role, Grant Williams, a blandly handsome journeyman who later gained a modicum of fame as a regular on the early 1960s TV detective series Hawaiian Eye, skillfully conveys the stages of Scott Carey’s malady from bewilderment and denial through desperation, terror, rage, and, at last, acceptance. A lesser actor would have spoiled the suspension of disbelief while a more glamorous lead might have put us at a distance from the character’s traumas. Williams deserves credit for the persuasiveness he brings to this tiniest of big roles—which remained, till his death in 1985, his biggest.

Why else does this movie endure? Perhaps because it freights commonplace objects with a menace that’s almost otherworldly, like Moorehead’s kitchen knives in that Twilight Zone episode. The only special effect in Shrinking Man that seems even mildly chintzy is the shimmering radioactive cloud that hovers over the sea like the flimsiest of shower curtains before it envelops Grant Williams’s body like a dime store shroud. The movie earns its historic stature through those oversized chairs, stairs, needles, pins, orange crates, paint cans, and balls of string that enhance one’s conviction that this is exactly what a walking, talking man deals with when he’s the size of an average bunny pellet. The near-fatal attack of Butch the Cat affirms one’s worst fears of what our pets really would do to us if we weren’t able to pick them up. And that damned spider, the movie’s true super villain, gave Arnold his second opportunity since Tarantula to spread arachnophobia among generations of thrill-seekers.

By today’s high-tech standards, these effects should come across as quaint and clunky. But six decades of technological innovation have not dulled this film’s overwhelming expression of how vulnerable we ultimately are, even to those aspects of the known world we take for granted. (Sidebar: As I write this, I hear that the U.S. Senate, by a vote of 50-49, has established that human beings don’t cause climate change. Guess there’s all kinds of gas clouding minds out there . . .)

| BUY THE BOXED SET |

|

| American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s (Two volumes) |

Matheson hoped his fantasy storyline would allow him to “explore an adult marriage relationship” (as he put the matter to his old professor). The result was a series of experiments in male sexual terror. Williams’s Scott vents his impotent rage to his devoted, if put-upon wife, Louise (Randy Stuart), as she looms like a giant over the doll house where he’s been forced to hunker down. Later, he seeks communion with a carnival dwarf, Clarice (April Kent). But he gets too small even for Clarice, and in confusion and despair, he bolts away from her, forever.

And then there’s the movie’s ending—perhaps the most ruminative, certainly the most upbeat of any something’s-out-to-get-us science-fiction movie of the era. Scott is stripped almost bare, physically and emotionally drained from vanquishing a foe he could have once simply eliminated with a firm application of shoe leather. He is staggering into a world where he will soon be little more than a sub-atomic particle. Yet he somehow feels more consequential, more human in his rapidly diminishing state than he ever did full-grown. Nothing about this optimism feels forced and gratuitous, owing to the “clean,” resolute craftsmanship of the magazine writer who dreamt the whole thing up in the first place.

Today, audiences would demand the kind of triumphant hero who vanquishes both his spider-nemesis and his malady. Here, Scott settles for something both larger and, well, smaller than what audiences expected. To this day, there’s a gratifying buzz to hearing somebody in such existentially challenged circumstances assert: “. . . Existence begins and ends in man’s conception, not nature’s. And I felt my body dwindling, melting, becoming nothing. My fears melted away. And in their place came acceptance. All this vast majesty of creation, it had to mean something. And then I meant something, too. Yes, smaller than the smallest, I meant something, too. To God, there is no zero. I still exist!”

Who needs special effects for this kind of rush?

Trailer for The Incredible Shrinking Man (2:07)

The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). Directed by Jack Arnold. Written by Richard Matheson, adapted from his novel, The Shrinking Man. With Grant Williams, Randy Stuart, April Kent, Paul Langton, and Billy Curtis.

Buy on DVD • Watch on Amazon • Watch on Google Play • Watch on Vudu

Gene Seymour spent most of the twenty-first century’s first decade writing movie reviews for Newsday. He also has contributed articles on music, literature, television, politics, and other distractions for The Nation, The Baffler, BookForum, CNN.com, and other outlets.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.