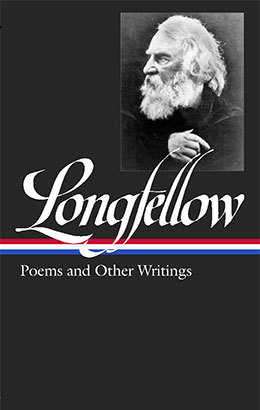

Paul K. Johnston is an Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, where he teaches a course on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow centered on Library of America’s collection of the poet. The following blog post is excerpted and adapted from a guide to Longfellow for the general reader that Johnston is currently preparing for publication.

Update 2020: Johnston is now the host of Fireside Poems, a podcast dedicated to Longfellow’s poetry. Learn more about the podcast and start listening here.

By Paul K. Johnston

Central both to Longfellow’s 1841 collection Ballads and Other Poems and to the rest of his career is “The Village Blacksmith,” in whose forge and anvil we see the emergence of what’s best in Longfellow’s verse: the fusion of his ideals with the solid things of life. The blacksmith’s work, like Longfellow’s, is both useful and, in its way, beautiful. It’s hard work, but not begrudged for that.

But some of the things a blacksmith makes are fetters and chains, and these must be broken. Longfellow lent his pen to the effort to break the shackles of slavery in 1842, after a trip to Europe in which he was inspired by meetings with Charles Dickens in London and, in Germany, the staunch anti-slavery poet and political radical Ferdinand Freiligrath. Writing in his cabin during a stormy return voyage, Longfellow produced seven of the eight poems that make up Poems on Slavery.

Published that December, the book met with a mixed reception, as even in the north in 1842 the United States was divided as to what should be done about slavery—and some preferred not to talk or hear of it all. But John Greenleaf Whittier, Longfellow’s friend and himself America’s preeminent anti-slavery poet, liked Poems on Slavery so much that he proposed to Longfellow that he run for Congress. Longfellow demurred, feeling that his best service to his country was as a poet. The overt political nature of Poems on Slavery was in fact a departure for Longfellow that he wouldn’t embark on again.

The political nature of these poems is partly what has restored them to admiration after a half-century of formalist literary criticism that saw them as sentimental and didactic. Just as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published ten years later, has been rehabilitated as a political statement on behalf of its marginalized characters, so too has Poems on Slavery. In a volume as concise as Stowe’s is expansive, Longfellow anticipates many of Stowe’s strategies and images. Just as Uncle Tom goes to heaven at the moment he perishes beneath the whip, so death carries home the noble slave of “The Slave’s Dream”:

He did not feel the river’s whip,

Nor the burning heat of day;

For Death had Illumined the Land of Sleep,

And his lifeless body lay

A worn-out fetter, that the soul

Had broken and thrown away.

Christianity both brings solace to “The Slave Singing at Midnight” and inspires the female slave owner of “The Good Part” to free her slaves—the resolution to the problem of slavery that both Longfellow and Stowe aimed at above all. The runaway slave of “The Slave in the Dismal Swamp” and the young girl sold into sexual bondage in “The Quadroon Girl” chapter of Uncle Tom’s Cabin are figures of pathos and sympathy alike, as are other similar characters in both works. The horrors of the Middle Passage are evoked by “The Witnesses”: skeletons in shackles lying half-buried in the sands of the bottom of the ocean.

Having opened Poems on Slavery with hopeful praise for the abolitionist William Channing, Longfellow closes it with “The Warning”—invoking, like Stowe at the end of her novel, a biblical prophecy of calamity for a nation that fails to put its house in order:

There is a poor, blind Samson in this land,

Shorn of his strength and bound in bonds of steel,

Who may, in some grim revel, raise his hand,

And shake the pillars of this Commonweal,

Till the vast Temple of our liberties

A shapeless mass of wreck and rubbish lies.

Not a call to arms, but rather a call to social action that will forestall a battle of arms, this is as far as Longfellow was willing to go in rousing his countrymen to face the issue.

Poems on Slavery, like Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin ten years later, could be considered a failure. Slavery didn’t come to an end in the United States through either changed hearts or peaceful political means. The failure of human sympathy led, as Longfellow’s unheeded warning predicted, to a terrible war. But Longfellow and Stowe had helped strengthen the anti-slavery sentiment of the North. More importantly for readers today, each modeled what it means to be an ally to the marginalized and the oppressed. My African-American students tell me how much it means to them that such allies existed then—which gives them hope that there may still be such allies today.