By Megan Abbott

Otto Preminger’s adaptation of Vera Caspary’s novel is more polished and studio-sleek than much of what would come to be called noir. But at heart, writes Megan Abbott, it ranks among the most tantalizingly subversive works in the genre.

“Who wants to play a painting?”

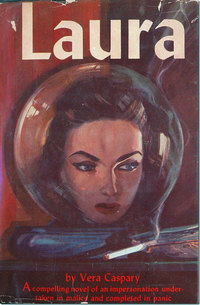

These were reportedly Gene Tierney’s words when offered the title role in Laura, based on Vera Caspary’s razor-sharp and silken-smooth 1943 novel.

One can hardly blame her. Caspary herself hated the draft of the script she was given and, in her memoir, recounts director Otto Preminger referring to her complicated and ambitious heroine as “a nothing, a non-entity.” (Caspary came to believe her battles with Preminger paid off and that the finished film, which she praised, reflected her input—in particular, a strengthening of Laura and greater emphasis on both her “generosity and romantic shortsightedness.”)

On its gleaming surface, and in some of its deeper reaches, Laura is a tale about everything but its presumptive center. Surrounded by bold, flashy characters who preen and probe and perform, Laura herself is the murky-eyed cypher, the gorgeous blank.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1940s |

Who wants to play a painting, indeed. The portrait is the thing. The flesh-and-blood woman is a complication, a set of contradictions that threaten to overturn the “Lauras” presented or created by her mentor, her lovers, her rivals. But that painting that rests above the mantelpiece, a swoony, romantic provocation—it offers no argument. Its power is not only the movie’s thematic fixation but also played out in the film’s creation, reception, and enduring legacy. The famous still of detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews), collapsed in a chair in front of the portrait, half-drunk and mesmerized, is the stand-in for scores of viewers of the film, haunted by its power to reflect back our own dreams and desires—for a past or imagined love, for the return of something lost, for anything at all.

And that power becomes Tierney’s power, even if she accepted it hesitantly. Consider David Raksin, composer of the movie’s legendary theme, himself caught in her snares:

She was so exquisite that you just looked at her and you knew why Dana Andrews had fallen madly in love with her. When I was working on the score, I kept looking at her all the time. I’d run sequences, and there’s this fabulous creature. You come across something marvelous, and it inspires you.

And to this day, a large part of Laura’s enduring fascination is its status as an exploration if not a celebration of male fixation, obsession, even a necrophilic romanticism that harkens back at least as far as nineteenth-century literature—as Edgar Allan Poe once said, “the death . . . of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetic topic in the world”—and forward to Vertigo and on. Indeed, novelist James Ellroy has repeatedly drawn connections between the film and a very real phenomenon common to homicide detectives like Andrews’s Mark McPherson and to other men—foremost himself. In Destination Morgue: L.A. Tales, he calls it “Laura syndrome”:

Homicide cops dig the gestalt. The title woman is lovely and perplexing. She’s a murder vic. The cop works her case. Laura’s portrait seduces him. She turns up alive. . . . Laura and the cop fall in love. It’s ridiculous wish fulfillment. It negates the hold of the dead. They inhabit your blank spaces. They work magic there.

Ellroy’s “Laura syndrome” looms largest with his own mother, murdered when Ellroy was a child. In his memoir My Dark Places, he writes of his unusual fellowship with Bill Stoner, the homicide detective who helps him investigate his mother’s death:

We shared a genderwide and wholly idealized crush on women. We were indictable coconspirators in the court of murder-victim preference. Bill reveled in the luxury of a sustained investigation with a probably dead suspect and negative outcome. It let him live with the victim and explore her life and honor her at leisure.

In this model, Laura’s function is to arouse, to provoke men to deeds heroic and obsessive and perverse and inspired. If the more traditional femme fatale is, as many film scholars have suggested, a symptom of male anxiety, Laura/Laura is an occasion for a (mostly, but perhaps not exclusively) male compulsion. And the genius of the film is it enacts this phenomenon while also dissecting it, eviscerating it. One can savor Laura and never see that the movie puts under the microscope just what it draws out in the viewer.

One feature of Laura’s reputation, particularly during its initial release, is that it’s a “B” picture story with (via Otto Preminger’s direction, the casting, the score) “A” picture sheen. But in some ways the movie has always been a bit of a masquerade. Not a B picture in disguise, but a movie you can watch two ways: as a movie about a detective falling in love with a dead girl and a movie about the way we all fill blank spaces with our own longings, our own subversive desires. And the trick of the movie is how deviously it puts you (as it put Raksin) in Mark’s place and you end up re-enacting the story offscreen. A contemporary review in The New York Times decides, unironically, the movie’s one weakness is that when Laura herself finally appears “she is a disappointment. For Gene Tierney simply doesn’t measure up to the word-portrait of her character. Pretty, indeed, but hardly the type of girl we had expected to meet.” Of course not. Because that Laura was your invention. Was Mark’s invention. And that of Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb) and Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price), and on and on.

Much like Vertigo after it, Laura encourages viewers to identify with characters who in daily life we might find troubled, and troubling. One of the most thrilling features of Laura is that, while more polished and studio-sleek than much of what would come to be called noir, at its heart it is among the most deviant. Every character’s got a “perversion,” a wayward or forbidden desire (an older woman for a younger, “kept” man; a seemingly closeted gay man playing Svengali to a woman in part so he can vicariously experience her relationships with men), and the film operates as a mirror chamber for these desires, like a finely faceted jewel flashing reflections everywhere.

The primary example is Mark’s longing for a dead woman. We witness his rising obsession as he finds excuses to stake out her home so he can bask in it, drinks her liquor, sits on her furniture, stares endlessly at her portrait and, in perhaps the film’s boldest moment, rustles through her bedroom drawers, fondling her . . . things. This necrophilic fixation is not subtext, as in much noir, but its open subject. Waldo himself pronounces it: “You’d better watch out, McPherson, or you’ll finish up in a psychiatric ward. I doubt they’ve ever had a patient who fell in love with a corpse.”

Laura’s “return from the dead” offers Mark a socially acceptable resolution, but it’s a dynamic recapitulated across all of Laura’s characters, all of whom have found ways to conceal or triangulate their wayward desires through more socially acceptable channels so they may take their pleasure remotely. Most fascinatingly, we watch Waldo use Laura to seduce Mark—a more sexually complicated Cyrano scenario. Waldo is turned on by turning on Mark via Laura. There’s a palpable charge in the scenes between Waldo and Mark (which begins with Waldo disrobing before Mark and overflows with 1940s Hollywood “code” for homosexuality). Mark can do what Waldo can’t (or doesn’t want to) with Laura and Laura can do what Waldo can’t but would potentially like to do with Mark. Hovering in the air are Mark’s own interests in Waldo, which are both business (he’s a suspect) and personal (he’s the one who effectively stirs Mark’s desires by creating a tantalizing verbal portrait of Laura to match the physical one). “You like a man better if he’s not 100 percent, don’t you Mr. Lydecker?” Mark notes in the novel. But no one in Laura is 100 percent anything—gay, straight, male, female, victim, suspect.

Thus, in the end, if we feel confident in the love match of Mark and Laura and its future, we are perhaps missing the point. Laura’s most subversive message is that it reveals all of us as shapeshifters, performers, altering our performance to hide our secrets and to get what we want—which, in the film’s logic, is always something we’re not supposed to want. In Laura’s world, desire is real, palpable, dangerous. It is our secret self, more potent than love, and more enduring.

Trailer for Laura (1:40)

Laura (1944). Directed by Otto Preminger. Written by Jay Dratler, Samuel Hoffenstein and Betty Reinhardt, based on Vera Caspary’s novel. With Gene Tierney, Dana Andrews, Clifton Webb, Judith Anderson and Vincent Price.

Buy the Blu-ray • Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Prime • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Megan Abbott is the Edgar award–winning author of seven crime novels and The Street Was Mine, a nonfiction study on hardboiled fiction and film noir. Her new novel, You Will Know Me, comes out in July 2016.

The Moviegoer, a biweekly feature from Library of America, showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.