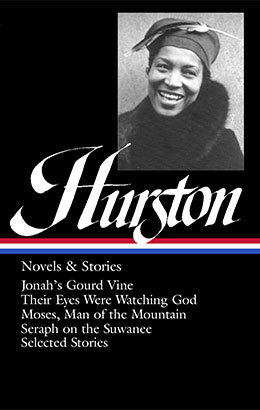

Library of America was honored to learn earlier this year that its collection Zora Neale Hurston: Novels and Stories has been selected by the University City Public Library of University City, Missouri, for its “Big Book Challenge,” a summer reading program that introduces adults to classic literature. Between now and August, participants will read and discuss three of the novels in the Hurston volume: Jonah’s Gourd Vine, Their Eyes Were Watching God, and Moses, Man of the Mountain.

The 2016 Big Book Challenge launched on May 25 with a keynote address by Dr. Rafia Zafar, Professor of English, African & African American, and American Culture Studies at Washington University in St. Louis and the editor of Library of America’s two-volume anthology Harlem Renaissance Novels. In a statement before the launch, Zafar said, “The Big Book Challenge offers this Library of America editor the chance to bring to her St. Louis community the beauty and dignity of an everyday black community through the loving, comedic vision of Zora Neale Hurston, an ethnographer turned novelist. Hurston’s ordinary folks—fractious, funny, familiar—speak not only to African Americans but any American who ‘gets’ the homely, straight-up knowledge found in every small town or big city neighborhood.”

In the following excerpt from her UCPL keynote, Zafar introduces Hurston’s best-known novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, and explores what makes its memorable heroine so far ahead of her time.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), Zora Neale Hurston’s now-classic second novel, has been called a fairy tale of southern black life, a world without lynchings, substance abuse, or back-breaking endless labor. But Janie Starks—while described as beautiful, with light brown skin and long tresses—is one Black Renaissance heroine who doesn’t attend Harlem parties in expensive dresses. Hurston gives us a working-class heroine of sorts, a sensual woman who nonetheless wants to be taken seriously. Janie ushers in the kind of black female character that modern readers of Alice Walker and Toni Morrison have come to expect. In the 1930s, though, such a protagonist startled—and so I’ll say a little more about this, perhaps the most notable of the three novels you’ll read.

As a teenager, Janie at first refuses an arranged marriage with a much older landowner. While her grandmother, who is raising Janie, sees security in Mr. Killicks, the girl sees an old man. Not long after the wedding, though, and without a backward look, Janie runs off with Jody Starks, a can-do big talker whose outsized ambition provides the erotic spark lacking in her life. Starks, the classic “git ’er done” American, provides Hurston with a canvas on which to paint another kind of black success story—not the one of making it in the urban north, but the one that hearkens back to a Booker T. Washingtonian “cast down your bucket where you stand” mindset. Like Janie, Jody offers a model of black selfhood new even to the relatively young body of African American literature.

The “lying sessions” in Gourd Vine—tall-tale sessions held in front of Jody’s store—show Hurston’s affection for, and understanding of, the kind of daily southern black life that is largely absent from the canon of Harlem Renaissance fiction. One long-running town joke, about one man’s skinny mule, nicely encapsulates that affection: “Yeah, Matt, dat mule so skinny till de women is usin’ his rib bones fuh uh rub-board, and hangin’ things out on his hock-bones tuh dry.” When Matt protests, and says the mule’s just plain mean, another neighbor responds by saying the animal would’ve trampled a child to death—except a gust of wind blew him “way off his course.”

Janie’s escape from an arranged marriage found supporters in the 1930s; readers may have found it trickier to endorse Janie’s rejection of her subordinate role in her second marriage. A whole-souled fulfillment eludes her until widowhood and an encounter with a charming, sexy-eyed younger man. In the eyes of “Tea Cake” Woods, Janie can do no wrong: she is beautiful, she likes to fish, she works in muddy fields alongside him, and she doesn’t nag about his gambling. That she will eventually return alone to the neatly appointed house Jody left her, points to the costs and caveats of educated black womanhood that Hurston herself couldn’t evade. If W. E. B. Du Bois saw the problem of the new century as one of race, Hurston knew, before we had such concepts as “intersectionality,” that long-prescribed gender roles would also, like the color line, be nearly impossible to escape.

© 2016 Rafia Zafar.