By Francine Prose

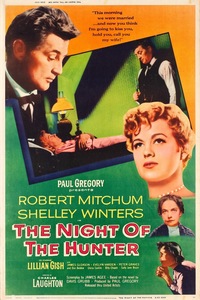

Indelible black and white imagery, James Agee’s extraordinary screenplay, and powerful performances by Lillian Gish, Robert Mitchum, and Shelley Winters combine to create a near-Biblical drama of the struggle between good and evil in this 1955 film.

If we were to measure a film’s achievement purely on the basis of the depth and the indelibility with which it has engraved an image (or images) on our minds, the winner might well be Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955). For some, the unforgettable image from the film is Robert Mitchum’s hands—the letters L-O-V-E tattooed on the fingers of his right hand, H-A-T-E on his left—enacting their grim wrestling match for the benefit of the (wary or transfixed, worshipful or sensibly skeptical) audiences gathered around Mitchum’s serial killer turned bogus, God-haunted preacher, the Reverend Harry Powell. And then there are the images which, throughout the film, signal the stages and rounds of the Manichean struggle between good and evil: between the deity and the devil.

The forces of good are concentrated in Lillian Gish, as Rachel Cooper, who protects the innocent children—John and Pearl—against the murderous predations of Mitchum’s preacher. Long after watching the film, we can still see her in silhouette, keeping a nighttime vigil on her front porch, a rifle across her lap. She is the person we want on our side, the sweet tough grandma willing to go further even than our own sweet tough grandma did, to keep danger and threat at bay.

For some, the image they cannot get out of their minds, however much they might wish to, is that of the children’s mother, Willa Harper (Shelley Winters), wearing her nightgown, her weed-like hair floating behind her among the weeds, sunk to the bottom of a river in the front seat of a Model T. Jeffrey Couchman’s fascinating book, The Night of the Hunter: A Biography of a Film, describes the ingeniousness with which cinematographer Stanley Cortez and art director Hilyard Brown staged this scene, a two-day process that involved a wax dummy of Willa, with its throat slit: “The car and its grisly passenger were submerged in a tank at Republic Studios. Cortez shot the scene using two cameras, one inside the tank and one outside, and huge arc lamps ‘to create that ethereal death-like something you had in the water.’ Brown created current by spraying water in from a hose, and he set a fig tree upside down in the tank ‘so that the roots of the tree looked like water willows.’”

Brighter souls may find themselves returning to the image of the two children, John and Pearl escaping down the river to safety beneath the enormous dark sky, twinkling with starry pinpoints of light. Like so many other plot turns and visual moments in the film, this one brings to mind the Bible. And if we are are unsure about which part of the Bible, exactly, that is, Rachel clears it up for us, and for the children. It’s the story of Moses in the bulrushes, only doubled: two little children instead of one, washing up on shore. Added to that is an evocation of Huckleberry Finn, but without the moral complexities that Twain’s characters must face as members of a slave-owning society. John and Pearl are purely good, the preacher purely evil. Yet the movie has the emotional complexity, and the ineluctable pull, of a primal fairy tale.

The film closely follows the novel by Davis Grubb that was published in 1954 and spent seventeen weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list. Producer Paul Gregory optioned it for his friend Charles Laughton; it would be the only film that Laughton directed.

Directors often talk, sincerely or not, about their respect for the book on which a film is based. Laughton meant it, and he and Grubb maintained a close working relationship throughout the making of the film. Couchman’s book includes a selection of the drawings that Grubb made when Laughton asked him to illustrate how he’d imagined certain scenes. As it happened, Grubb could draw, and Couchman points out the similarities between his drawings and those of William Blake and the German Expressionists. Several of these drawings made it into the final cut, for example, the preacher’s shadow appearing on the children’s bedroom wall, and the long shot of the preacher as seen by John, who is hiding in the hayloft.

| READ THE SCREENPLAY |

|

| James Agee: Film Writing and Selected Journalism |

The director’s relationship with the screenwriter was less seamless—less amicable—than his connection with the novelist. One can understand why James Agee was drawn to the project and why the filmmakers would think of him. More than a decade before, Agee had worked with photographer Walker Evans on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a book-length study of sharecroppers in the Depression-era South. The Night of the Hunter’s milieu is one that Agee was believed, and believed himself, to know a great deal about. (Robert Mitchum wanted to make the film entirely in West Virginia, to more closely evoke the ambience of the novel, but for budgetary reasons it was filmed mostly on a Studio City lot and on locations in the San Fernando Valley.)

Legend has it that Agee submitted a first draft that was over 400 pages long. Couchman rebuts this myth. In reality, the number of pages was 287, roughly double the length of the shooting script, but hardly “bigger than a phone book” (the phrase is Gregory’s). Agee did go on at great length about this or that minor character, adding monologues and elaborations that never made it to the screen. Still, Couchman writes, ”With few exceptions, even scenes that Agee invents arise straight out of lines or situations in the novel.” Laughton kept Agee working on the film even though they tangled on the rewrites. Couchman reprints in full a cordial memo that Laughton wrote to Agee in the thick of the revisions, the director suggesting tweaks one professional to another.

In any case, the published version of the script that appears in Agee On Film and in the Library of America edition of Agee’s Film Writing and Selected Journalism is a model of thoughtful and effective page-to-screen adaptation. It’s extraordinarily faithful to the book, even as it shortens certain scenes and rearranges the sequence of others for greater dramatic effect. This is especially apparent in the economy with which the film conveys essential information about Ben Harper, his crime, and the hidden cache of loot that the preacher (who shares a prison cell with Ben) is determined to find, regardless of the hideous cost. Again, though, it is the power of the image (as much that of dialogue or setting) that stays with us. What could have been a familiar scene—two criminals sharing a prison cell, one attempting to pry a secret out of the other—becomes something wholly new and shocking as the preacher’s head appears—upside down!—when he leans over from the top bunk to better hear what Ben is mumbling in his sleep.

Much has been made of Laughton’s decision to shoot the film in black and white; Couchman writes persuasively about Laughton’s debt to early silent film and to the films of the German Expressionists. In any case, having seen the film, we are utterly unable to imagine it in color. This is partly because the clear and sharp division between black and white mirrors the clarity and the extremity of the film’s divisions between good and evil. Except perhaps in the cases of Ben Harper, who commits a crime out of poverty and desperation, and Willa, who convinces herself that marrying Powell is her salvation, very little in the film occurs in any sort of “gray area” of moral ambiguity—of characters doing the wrong thing for the right reasons.

Harry Powell is not so much a character as a personification of everything that is vile. Many villains have a single fatal flaw (jealousy, envy, greed) or even a bit of virtue mixed in with their sins. But Harry Powell displays a rather high percentage of the seven deadlies; he’s greedy, angry, arrogant, and his twisted psyche converts lust into homicidal rage. When we first meet him, he is riding along, trying to remember how many women he has killed. Laughton took Grubb’s sketch (so like a drawing by George Grosz) of the preacher at the burlesque theater and turned it into a sort of terrifying visual joke. As the dancer performs, much to Harry’s disgust, his H-A-T-E hand twitches convulsively in his pocket and his switchblade knife springs open, slicing through his coat in a grimly funny simulacrum of an erection, or an orgasm.

What’s striking is how many of the artistic decisions that Laughton made seem to us to have been wholly correct. Decisions about casting, for example: Couchman tells us that Laughton originally had Laurence Olivier (or more surprisingly still, Jack Lemmon) in mind for the role of Harry Powell. But we can’t think of the preacher without thinking about Mitchum: his sleepy, slightly hooded eyes, his cleft, oddly angled jaw, the way the hair curves up from his forehead. Nor can we think of anyone but Lillian Gish for the role of Rachel, or of Willa Harper as anyone but Shelly Winters, in a role that would prefigure one she played in Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita: the hapless, yearning, not terribly bright widow who falls in love with the predator whose sights are set on her child.

The evil step-parent is, of course, a familiar figure from classic fairy tales, and at several points during the making of the film Laughton referred to the similarity between the work he envisioned and a fairy tale. “It’s a really nightmarish sort of Mother Goose tale,” he told Gregory. “A beautiful ballad, folk-tale, and real Americana.” As the film progresses, we may be reminded of different stories we knew as children: Hansel and Gretel wandering in the woods, escaping their murderous stepmother’s plans for them. But the story I found myself thinking of most often is Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen”: an innocent little boy and girl must contend with the dark and often erotic dangers of the strange new world in which they find themselves. By the end of the film, the preacher has come to seem like one of the wolves who—in tales ranging from “Little Red Riding Hood” to “The Three Little Pigs”—is wounded, maddened, reduced from the status of a rogue demon to that of the animal that indeed he is, and always was.

The Night of the Hunter did not do well commercially or critically upon its release. Most contemporary reviewers who praised its power also condemned what they considered “artiness.” But like something out of another kind of fairy tale—the sad story with the happy ending—Laughton’s film is now generally acknowledged as a work of art and a classic. It is the tale of cream rising to the top, of the scullery maid recognized as the true princess, of greatness and virtue making its presence felt. I can only be grateful for the way that the film’s fortunes played out. It went from the big screen to television much more rapidly than was common at the time, or at any time. And it was on television that I first saw the film, when I was a child, and where its images became inscribed on my mind. Now it can be seen in occasional theatrical revivals, or on DVD or streamed into one’s home, giving us all a chance to again drink in the images we cannot forget, and to discover that the film remains as powerful, as original, as haunting and beautiful as we remember.

Turner Classic Movies airs The Night of the Hunter on July 18, 2016.

Trailer for The Night of the Hunter (1:55)

The Night of the Hunter (1955). Directed by Charles Laughton. Written by James Agee, based on Davis Grubb’s novel. With Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, and Lillian Gish.

Buy the Criterion Collection DVD/Blu-ray • Watch on iTunes • Rent from Netflix • Watch on Vudu

Francine Prose is the author of more than twenty works of fiction, most recently Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932. Her nonfiction books include The New York Times best seller Reading Like a Writer. A former president of PEN American Center, she is a Distinguished Visiting Writer at Bard College.

The Moviegoer, a biweekly feature from Library of America, showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.