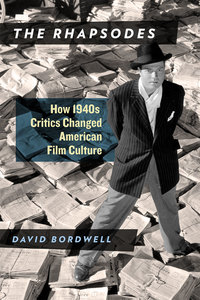

Just published by University of Chicago Press, The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture is film scholar David Bordwell’s study of four writers—Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, and Parker Tyler—who helped inaugurate the tradition of serious critical engagement with Hollywood filmmaking in this country and cleared a path for later critics like Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, and Roger Ebert.

“Neither highbrow nor lowbrow nor middlebrow, neither pure journalists nor Algonquin intellectuals,” Bordwell writes, “these four created a daredevil criticism that was audacious and dazzling.” In the highly entertaining survey that follows, he is equally attentive to the four writers’ idiosyncratic prose styles and to the strategies they used to argue that mainstream movies were an art form worthy of serious study. For those curious about his choice of title, Bordwell explains that the name Rhapsodes alludes to “the ancient reciters of verse who, inspired by the gods, became carried away. The tag aims to emphasize the exuberance of [these critics’] vernacular prose.”

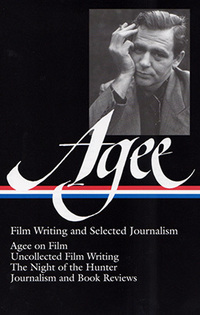

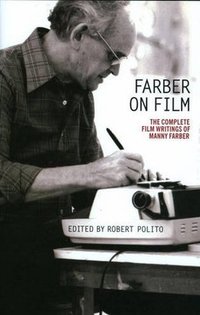

The Rhapsodes will interest readers familiar with Library of America’s collections of film writing, most obviously James Agee: Film Writing and Selected Journalism and Manny Farber: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber, along with American Movie Critics: An Anthology from the Silents Until Now, which includes selections by all four writers.

The Jacques Ledoux Professor of Film Studies Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Bordwell shared some insights from The Rhapsodes with Library of America via email.

LOA: You assert that these four critics “remain far more provocative and penetrating than nearly anyone writing film criticism today.” What makes four writers from the middle of the twentieth century provocative in 2016?

Bordwell: I’d argue that their provocative side for us today stems from three sources. First, they weren’t out to massage the sensibilities of their readers. Ferguson, writing in the fellow-traveling New Republic, could praise Hollywood versions of British imperialism and castigate Soviet propaganda exercises. Agee knew that his readers were unlikely to appreciate The Human Comedy’s sentiment, and he tried to convince them that the movie had something genuine in it—even though he also raged against its evasions. Farber, tracking Ferguson in refusing to satisfy NR readers, wrote a harsh denunciation of The Rainbow at the height of U.S.–U.S.S.R. solidarity. Tyler, as a Surrealist, practiced calculated outrage by proposing wildly Freudian readings of minor Hollywood pictures. (Iris Barry of MoMA warned readers that the world might not be ready for him.) All four tried to shake their readers out of their habitual tastes and assumptions about movies, and Hollywood movies in particular.

That brings me to my second source of provocation: These critics wanted to explore ideas—about what cinema can do, and how, in particular, Hollywood movies worked. Today’s critics seem remarkably incurious about the possibilities of the film medium; nobody worries about what’s “cinematic” any more. Maybe that’s because so many great achievements lie behind us that we think it’s overweening to try to grasp it all. But around 1940, the world of film didn’t seem so big, and these critics faced a Hollywood industry that was still in the process of defining itself.

So Ferguson could speculate on the craft of the mature sound movie, how it had learned to tell stories cleanly and quickly and still convey something of ordinary social life. Agee could look to Hollywood for moments of poetic illumination arising out of the concreteness of a dramatic situation. Farber’s ideas revolved around considering cinema as an art of emotional expression, conveyed through the quickened craft that Ferguson praised. And Tyler swiped ideas from anthropology and psychoanalysis to posit that Hollywood films reenacted ancient myths and unconscious impulses. (It sounds more academic than it was; his use of these ideas was pretty promiscuous.) I don’t see many reviewers summoning up such provocative ideas today. It helped, of course, that each of these critics was deeply versed in another art form—literature for Agee and Tyler, jazz for Ferguson, and visual art for Farber. Today’s critics, academic or journalistic, aren’t as widely cultivated as these cosmopolitan intellectuals.

Finally, there’s the matter of style. Owen Gleiberman’s recent memoir Movie Freak: My Life Watching Movies reminds us that popular criticism—hyphenated adjectives! exclamatory interjections!—has become a spasmodic parody of itself. But my four writers cultivated distinctive styles that still crackle unpredictably. Agee’s roundabout self-interrogations, Ferguson’s wisecracks, Farber’s sardonic hyperbole and understatements, and Tyler’s sidewinding coinages (“Hepburnesque Garbotoon”) make their criticism permanently provocative. For me, each man’s sheer verbal panache is central to his appeal.

LOA: Your book about four pioneering American film writers arrives just after one of today’s most prominent critics, A. O. Scott of The New York Times, felt the need to write a book-length defense of his profession. In the context of Scott’s book, what can looking back at Ferguson, Agee, Farber, and Tyler tell us about the state of the art today?

Bordwell: My four critics didn’t agonize so much about the place or need for criticism; that may reflect the fact that criticism was then still viable literary work, and all of them made a living by writing. Still, there are several points of contact with Scott’s book. I’ll take two.

Scott revives the question of whether criticism may itself be considered an art. Although he’s somewhat equivocal on whether great criticism can equal a great artwork, no one doubts that a critical piece may be as valuable as an essay on any subject. One of my main points in The Rhapsodes is that these writers gave us free-standing essays that yield literary delight and power.

Second, Scott thinks that criticism flourishes when artist and critic conduct a dialogue, either tacit or explicit. The four critics I discuss subscribed to this in one way or another. Ferguson, who enhanced his understanding of jazz by following bands and talking to players, realized that he had a lot to learn by visiting Lang and Wyler. He always wanted to know the craft from the inside. Agee had a similar impulse. As a young man he wrote imaginary screenplays, and after he became a critic he used his entrée with Chaplin and Huston to crack into moviemaking. Farber’s art writing reveals deep craft knowledge about how painters achieved their effects, and his sensitivity to image-making made him a discerning critic of visual technique. Tyler, who associated with avant-garde filmmakers and played in a Maya Deren film, always believed that critic and artist could learn from each other, even when they disagreed about the value of this or that work.

LOA: By focusing on Manny Farber’s Forties work, you show that his aesthetic and attitudes in this period were markedly different from his “classic” pieces of the Fifties and Sixties. Was he actively suppressing that earlier criticism by not including it in the Negative Space collection, in 1971?

Bordwell: I don’t think he was suppressing his juvenilia, but I feel sure that his most famous long-form pieces of the 1950s and 1960s, “The Gimp” and “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art,” did crystallize his new perspective on Hollywood. And while writing with Patricia Patterson for Artforum and other journals, he hit upon a fresh approach to European film and avant-garde cinema. So I think it’s natural that he’d want the Negative Space collection to reflect his most recent attitudes while preserving his most mature voice. And doubtless the publisher wanted both to keep the size under control and to highlight films and filmmakers still salient for readers.

There’s another factor, around the title itself. In The Rhapsodes I examine what “negative space” meant in Farber’s Forties milieu. I think that concept, as developed in the art world of the time, does shed some light on what he wrote in particular reviews. But by the time he prepared his anthology, he expanded the idea metaphorically to include not only a director’s characteristic use of pictorial space but also “the command of experience which an artist can set resonating within a film,” and that in turn involves the widest compass of the viewer’s imagination. It’s possible that including earlier pieces that didn’t use “negative space” in quite that way would have seemed out of keeping with his new inclinations.

For my money, I wish he had included a few more of those Forties pieces—if only to point up that he believes “illustrative naturalism” came to an end in the early Fifties. His review of The Searching Wind, for example, clarifies this idea and helps us understand what he objected to in Citizen Kane.

Incidentally, I’m very happy to learn that Robert Polito is assembling a collection of Farber essays on other subjects. I consider his painting criticism superior to a lot of what was published at the time, though I don’t think that’s been recognized. In the book I argue that he’s ahead of Clement Greenberg, who was in thrall to one big idea.

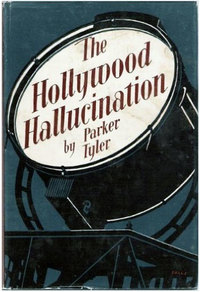

LOA: In many ways, Parker Tyler seems like the most elusive of these four writers today. Can we speak of a Tyler legacy in contemporary film culture, whether among critics or filmmakers themselves (like Guy Maddin or John Waters)?

Bordwell: I don’t think that Tyler has had the legacy he deserves. I’m not aware that people interested in gay aesthetics and culture read him much, which is a pity.

That may be because he was fundamentally committed to high art. He couldn’t abide what he saw as the 1960s underground’s sloppy technique and its lack of standards. He was careful not to go all-out Camp, because he still retained a dandyish, Cocteau side: a love of classic art, mythology, and High Modernism, all filtered through Parisian Surrealism. I don’t think he had today’s affection for over-the-top Hollywood. Old films that Maddin and Waters genuinely love would be for Tyler enjoyable instances of Hollywood’s protean energies, but not a patch on a masterpiece like The Rules of the Game. Still, I have to wonder what he’d think about weird pastiches like Maddin’s The Heart of the World and The Forbidden Room, which show such devotion to the silent avant-garde.