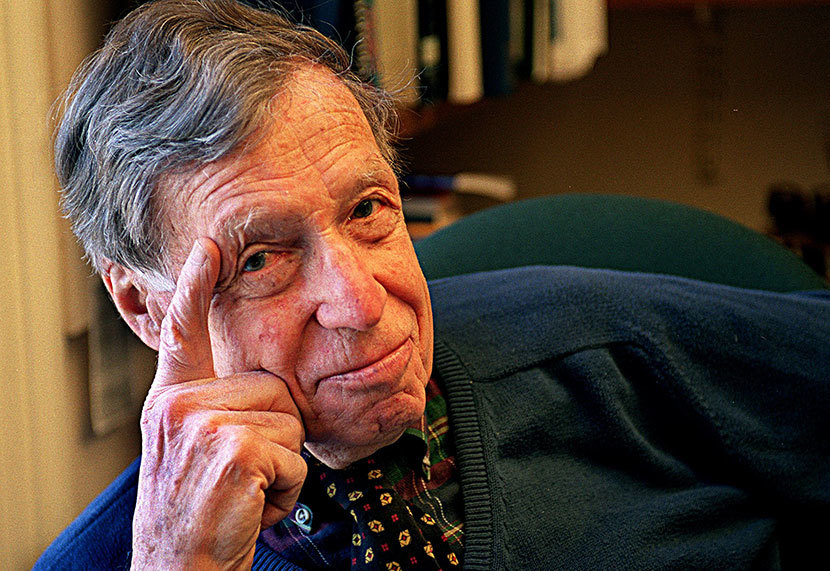

Library of America mourns its founding president and Life Trustee Daniel Aaron, who died of complications from pneumonia last Saturday, April 30, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was 103.

The Victor S. Thomas Professor of English and American Literature Emeritus at Harvard University, Aaron wrote several influential works of literary history and criticism and was awarded the National Humanities Medal “for his contributions to American literature and culture” by President Barack Obama at a White House ceremony in 2010.

In the late 1970s, he was part of a small group that took up Edmund Wilson’s call for an authoritative edition of great American writing for the general public—a project that led to Library of America’s founding in 1979. Aaron served as LOA’s founding president from 1979 through 1985 and as a Life Trustee in the following decades.

A “visionary” approach to American literature

From the beginning, it wasn’t just the idea of LOA that drew notice, but the way in which Aaron and LOA Vice President Richard Poirier shaped the series, opening it up to all kinds of writing beyond a narrowly belles-lettristic tradition—yet always with the stipulation that the work have “literary quality and historical significance.” His eclectic taste and wide range were embodied in the LOA series, which quickly earned a reputation for challenging assumptions about what constituted essential American writing. To cite one early example, Jack London—a popular, influential writer who was nevertheless not quite considered a canonical author at the time—was published in the series in its first year, winning acclaim in outlets ranging from the Wall Street Journal to the Los Angeles Times Book Review. In the following year, LOA reissued the great narrative historian Francis Parkman’s two-volume France and England in North America, a monumental chronicle that had been out of print for decades. These bold, fresh choices made news, with both Vanity Fair and The New Yorker both running lengthy appreciations of the Parkman volumes.

Another of Aaron’s innovations was publishing a comprehensive collection of a writer’s work, rather than just one or two titles. In some cases, such as Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Henry James, or William Faulkner, the entire body of the author’s work is included in the series, which led Morris Dickstein to remark in The American Scholar: “The Library of America has done more to establish the American canon than any other institution. It advanced the novel idea that American writers have a real corpus of work, to be read whole, not simply a patchwork of isolated successes.”

Library of America President Cheryl Hurley said: “Dan Aaron was a visionary who recognized that American literature is the key to understanding the nation’s history and character. He wanted us to take full possession of our written heritage, an idea that led to the creation of the Library of America—publishing for a wide audience authoritative, lasting editions of America’s best and most significant writing.”

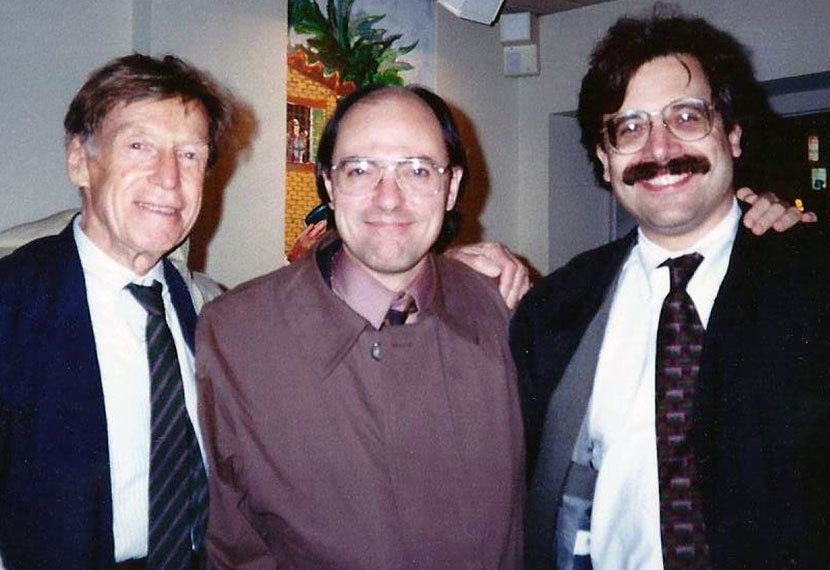

Aaron’s wide-ranging contacts in the literary and scholarly community were also an asset in LOA’s early years. As Hurley told the Boston Globe, “When you’re a startup you have to get people to work with you. Dan was our secret weapon. He knew everyone in the academy. People liked him a great deal. He was a respected scholar—and diplomatic.” Outside the academy, meanwhile, Aaron was on friendly terms with a host of major twentieth-century writers such as Saul Bellow, Truman Capote, Ralph Ellison, Robert Frost, Lillian Hellman, Mary McCarthy, Czeslaw Milosz, Charles Olson, and V.S. Pritchett, in addition to Edmund Wilson.

Library of America Trustee Andrew Delbanco, Alexander Hamilton Professor of American Studies at Columbia University, offers the following reminiscence of Aaron:

When I first met Dan in the mid-1970s (“Professor Aaron” to me then—and in some measure ever since), he was helping to create the Library of America and I was a graduate student, alternately nervy and nervous. He was intimidating. But his vast knowledge was exceeded by his curiosity, which made him a great example of what he wanted all of us to be: a lifelong learner. He had charm, wit, and sophistication, but none of the pretension that characterized many academics of his eminence.He also had an enviable equanimity, which was mistaken by some people for cool detachment, but he was drawn to passionate people—perhaps because they expressed a restrained side of himself. He never pulled rank. He never made one feel incompetent or inferior, although he knew much more that most of us could ever hope to know. He was almost aggressively unsentimental, but he had great warmth, and through his teaching and writing he showed how America could be better if only we lived up to our own ideals. None of us will see the likes of him again.

The “Americanist”

Daniel Baruch Aaron was born in Chicago on August 4, 1912. He graduated from the University of Michigan in 1933 and in 1943 received a doctorate from Harvard University—the first degree Harvard ever awarded in its program in the History of American Civilization. Aaron then taught at Smith College from 1939 to 1971, the same year he joined the faculty at Harvard. (One of Aaron’s students at Smith College was Betty Friedan, who later thanked him in the acknowledgments to The Feminine Mystique in 1963.)

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Aaron came to be seen as a founding figure in the field of American Studies. Among his more influential works is Writers on the Left (1961), which traces the uneasy involvement of American writers with communism in the first half of the twentieth century. Reviewing the book in the New York Times, Irving Howe called it “admirable, indispensable, a testimonial to what is best in American liberal scholarship.”

Another of his best-known books is The Unwritten War (1973), a study of Civil War literature that, in the words of the Virginia Quarterly Review more than twenty years later, “blended exquisite literary sensitivity with a grim understanding of the gravest political and moral historical crisis of the republic.”

In his 2007 memoir The Americanist, Aaron refers to himself as a “native son neither estranged from the collective American family nor unreservedly clasped to its bosom.” That characterization echoes the famous opening words of Writers on the Left, where Aaron writes: “American literature, for all its affirmative spirit, is the most searching and unabashed criticism of our national limitations that exists.”

In the words of LOA Trustee G. Thomas Tanselle: “Dan’s role in the founding of the Library of America can be regarded, I think, as the most far-reaching of his many accomplishments. And among his numerous circles of friends, none could have been more devoted to him than his LOA associates. I have many warm recollections of meetings with him in the office, at the Century Association, and in my apartment; on every occasion his deep immersion in literature was evident, along with his belief in the humane values it inspires.”

And, from Library of America Publisher Max Rudin: “Dan Aaron was a man of astonishing energies—of body, mind, and spirit. Not to mention the best-read person you could ever hope to meet. We are lucky to have known him, worked with him, and learned from him. Library of America could not have had a better or wiser founding president.”

Today we remember the many achievements of our friend and colleague’s long and distinguished career and offer our condolences to his family.