By David Denby

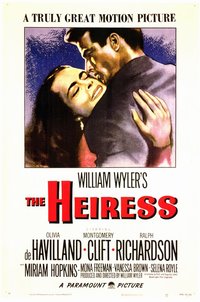

With Olivia de Havilland in her Oscar-winning performance as the guileless title character and a “fresh, eager” Montgomery Clift as an amiable fortune hunter, this 1949 classic boasts its own concentrated beauty and potency.

At the beginning of the first and best movie adaptation of Washington Square, we see the following: a petit point of the square itself, which fades into a photograph and then a kind of tableau vivant—carriages moving before a handsome townhouse, a boy corralling some fowls, life bursting out all over; and we hear the familiar French song, “Plaisir d’Amour” (“Plaisir d’amour ne dure qu’un moment. Chagrin d’amour dure toute la vie”), all of which is a slightly cloying and over-insistent setting of the period for the American audience. In 1949, the great Hollywood director William Wyler (The Letter, The Best Years of Our Lives) mounted an adaptation not of Washington Square itself, but of The Heiress—the theatrical version of James’s novel which the writing team of Augustus and Ruth Goetz had brought to Broadway in 1947. Watching the opening scenes of The Heiress, one feels a certain exasperation: All this conventional busy-ness (Olivia de Havilland, as Catherine Sloper, throws her formal gown over her head and then runs down the stairs like a sixteen-year-old) seems wrong for James’s study of domination, submission, love, and rebellion, an intense drama built on blunt exchanges and pages of psychological analysis. But The Heiress, despite certain alterations of James’s drama, has a concentrated beauty and potency that has never been equaled by any other adaptation of James.

| READ THE BOOK |

|

| Henry James: Novels 1881–1886 |

Like The Europeans, which was published in 1878, Washington Square, from 1880, combines humor and an acute and sometimes merciless perception of the way the world works. No matter how delicate James’s observations, his insistence on the hard facts of money, power, influence, and property fuels the engine of his stories. In Washington Square James lays such hard facts within the structure (though not the moral simplicity) of a romantic fable. Young Catherine Sloper, an heiress of the 1840s, falls in love with the highly available Morris Townsend. But Morris is despised by Catherine’s masterful father, Dr. Austin Sloper—so thoroughly that Dr. Sloper threatens to disinherit Catherine if she doesn’t withdraw from the courtship. The young woman, then, is a princess held captive in a castle—in this case, a finely proportioned New York townhouse with a drawing room, a study, decanters of brandy and claret. It is clear to Doctor Sloper, and to us—though not at first to Catherine—that the interloper wants the castle and the yearly income that goes with it much more than the princess.

James had used the fairy-tale framework before. In The American (1875), a crude but resourceful and good-hearted American businessman, Christopher Newman, lays siege to a young widow in Paris, a member of an old aristocratic family that looks unfavorably on a possible alliance with a “commercial” suitor. After complicated maneuvers and some melodramatic contrivances, James sends the American home in defeat. Washington Square is a saturnine revision of the fable. This time his princess is, of all things, a shy young woman. “She was not ugly; she had simply a plain, dull, gentle countenance. . . . She was excellently, imperturbably good; affectionate, docile, obedient, and much addicted to speaking the truth.” And her besieging knight and would-be savior is not a man of honor, nor a resourceful entrepreneur, but a smiling charmer, extraordinarily good-looking—“beautiful” in Catherine’s startled eyes—but also feckless, evasive, greedy, lazy, and generally unworthy.

Catherine, who receives Morris’s protestations of love rapturously, comes alive for the first time in her life. She glows, she is sexually awakened, though James would never put it that way. Will they marry despite the doctor’s disapproval? Should they? Of Morris’s mercenary intentions, there can be no doubt. Still, many readers, and not all of us sentimentalists, will ask why Catherine can’t have her handsome, worthless man even if it makes her happy no more than briefly. And isn’t she better off as an unhappy wife with children than as a spinster? Washington Square is a book which forces the reader constantly to interrogate what he is reading. Dr. Sloper has lost his wife, Catherine’s mother, a beautiful and brilliant woman. When he forbids the marriage, does he do it out of love for his daughter, as he tells himself and Catherine? Or is he motivated by something hidden and spiteful—rage at the boring girl, who is so painfully unworthy of the doctor’s dead wife? Catherine’s only virtue, in Dr. Sloper’s eyes, is obedience. Marrying is a betrayal.

The most important dramatic action of the novel is not Catherine’s realization of Morris’s true nature (that’s inevitable and not surprising) but her more painful and difficult realization of her father’s feelings toward her. In the end, she rejects both men as selfish and manipulative. She achieves not a feminist triumph but a spiritual and moral triumph: She preserves her integrity; she discovers her will, a proud self-sufficiency.

The Goetzes’ play was a success; Olivia de Havilland, seeing it in New York, wanted to star in a movie version, and she asked William Wyler, fresh off his triumph with The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), to take it on. Wyler agreed, and persuaded Paramount Pictures to let the Goetzes adapt their own work for the screen. De Havilland was joined by Sir Ralph Richardson and Montgomery Clift.

Most centrally, the Goetzes maintained the ambiguity of the novel: Dr. Sloper is exactly right about Morris, yet his judgment seems shriveled by misanthropy and resentment. The contraries are held in place by Richardson, one of the great eccentrics among movie stars. His eyes recessed behind a heavy brow and above a shapeless nose, his voice driving and precise, Richardson exudes a furious intellectual energy that shades into melancholy and a meditative distance. Around the house, where he is absolute master, his bonhomie is tinged by nasty irony. He cheers himself up by teasing the mediocrity of his female companionship—not only Catherine but her scheming, fatuous, chattering Aunt Penniman (Miriam Hopkins), who serves as an advocate of Morris’s cause. Morris, however, is a worthy opponent, and Richardson looks at Montgomery Clift with gloating pleasure. This beautiful imposter is someone he can defeat.

In 1997 the Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Holland cast Jennifer Jason Leigh as Catherine and Ben Chaplin as Morris in an almost hysterical adaptation of James’s novel, substituting erotic anguish for the author’s urbane analysis and potent checked emotions. Wyler’s steadiness is much more impressive than Holland’s bravura. Wyler gives the intimate scenes a quality of sustained psychological observation rare in American movies; his work is unusually blunt. Clift was then twenty-eight, and in the early stages of what looked like a starring career as a romantic lead. In the fifties and early sixties, his extreme sensitivity could be unnerving, as if he were indecisive about everything, but in The Heiress he’s fresh and eager. He brings to it not just his rakish smile and handsome features but a slight hesitating gentleness combined with self-deprecating humor. He’s likable—anything but a garden-variety cad. Paramount, which may not have quite understood James’s story, insisted that Morris be made sympathetic, and this bit of Hollywood thinking, reinforced by Clift’s co-operation, actually works in the movie’s favor. As Clift presses Morris’s advantages—youth, good looks, and the possession of Catherine’s love—we notice, to our amazement, that Morris is easily wounded. He wants and needs approval, even from the man whose claret he would like to drink and cigars he would like to smoke. We may want Morris to be successful even as we see clearly—and devastatingly—why he can’t be.

Olivia de Havilland’s Catherine is less guarded than we imagine the character from the book. Her eyes widen when she first meets Morris—can this man be interested in her?—and her mouth falls open in amazement when he offers his love. She allows the undercurrents of fear and desire to break through the surface—her Catherine is too naïve to know how much she is revealing. Catherine’s shock when she realizes Dr. Sloper doesn’t like her, that he is motivated by contempt rather than love, is a developing moment of consciousness which de Havilland prolongs and the strongest, most original scene in the movie. Throughout, Wyler favored Olivia de Havilland’s vibrant and detailed work—the camera catches more of her feelings than it does Clift’s, and the editing emphasizes her when they are together.

De Havilland won an Academy Award for her performance (the movie won four Oscars in all), but The Heiress was not a big hit, perhaps because many in the audience rooted for Catherine and Morris to run away together. The Goetzes retained James’s “unhappy” ending, though they spiced it a bit for popular taste. Catherine turns toward vengeance, taunting her father as he’s dying with her refusal to say she won’t marry Morris, her boast that she might waste her money on him. Years later, she allows Morris to think she will run away with him, only to leave him outside, pounding on the locked door. Catherine becomes one who does evil unto others to make up for what was done to her—which is a cruder version of James’s idea of pride and self-sufficiency. Still, the heart of the book is there on screen.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents The Heiress in 35mm on May 10, 2016.

Turner Classic Movies airs The Heiress on July 15, 2016.

Original theatrical trailer for The Heiress (2:51)

The Heiress (1949). Directed by William Wyler. Written by Augustus and Ruth Goetz from their play, an adaptation of Henry James’s Washington Square. With Olivia de Havilland, Ralph Richardson, Montgomery Clift, Miriam Hopkins.

Buy the DVD • Rent from Netflix

David Denby is a staff writer at The New Yorker and has worked as a movie critic at The Atlantic, The Boston Phoenix, New York magazine, and The New Yorker. His latest book is Lit Up: One Reporter. Three Schools. 24 Books That Can Change Lives.

The Moviegoer, a biweekly feature from Library of America, showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.