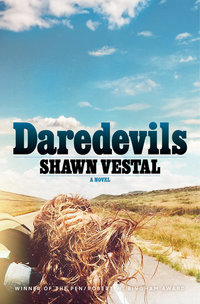

Our series of guest blog posts by writers of fiction, poetry, essays, and history continues today with a contribution from Shawn Vestal, whose debut novel, Daredevils, arrives this week from Penguin Press. A coming-of-age story set in the American West in the 1970s, Daredevils features a Mormon fundamentalist community, teenage lovers on the run, and cameo appearances by someone who may or may not be Evel Knievel, the motorcycle stunt performer whose exploits were an indelible part of ’70s pop culture.

Vestal’s novel has already won the admiration of his contemporaries, with Megan Abbott calling it “something fresh, vital and wild” and Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, praising it as “part American Dream and part American Gothic. . . . lean, fierce, and dangerous.”

There is a much-debated mystery in the early sections of The Ambassadors, the exquisitely repressed Henry James masterpiece.

The main character, Lambert Strether—through whose consciousness we will experience the novel—is making friends with a new confidante. He has traveled from America to Europe to bring home the wayward son of his would-be fiancée, a widow with a manufacturing fortune back home in Woollett, Massachusetts. But Strether doesn’t want to tell his new friend just what it is they make back in Woollett, feeling that the little item is vulgar and feeling that he has entered a more sophisticated realm. He goes to great lengths in his refusal, until it takes on a kind of extra potency—and then he promises to tell her later.

But it may even now frankly be mentioned that he in the sequel never was to tell her. He actually never did so, and it moreover oddly occurred that by the law, within her, of the incalculable, her desire for the information dropped and her attitude toward the question converted itself into a positive cultivation of ignorance. In ignorance, she could humour her fancy and that proved a useful freedom. She could treat the little nameless object as indeed unnameable—she could make their abstention enormously definite.

A lot of people have speculated what the object might be, from a “toilet article” to a button hook to a toothpick. But this guessing misses the point: It doesn’t matter what is manufactured in Woollett. What matters in The Ambassadors is the presence of, and the attitude toward, the omission itself. It tells us worlds about Strether, and it tells us worlds about his new friend, and it tells us as much as we need to know, if it’s not clear by that point, about the way the novel will operate. The Ambassadors exhibits at every stage a genius for handling what is not being directly spoken of, an ability to move gracefully and suggestively around the subject at hand. James will detail every ripple in the pond, but never name the stone. This style mimics Lambert’s own consciousness—he is very happy not to know certain things that he should know—and it also reflects the nature of the sophisticated social discourse in which he finds himself thrust. Abstentions become enormously definite.

The novel is full of secrets, the ones Strether keeps and, more importantly, the ones kept from him. His misapprehension of the central secret—which must also be the reader’s misapprehension—is crucial to the operation of the whole narrative. What Strether doesn’t know or admit is at the forefront at all times. He is amply willing to live with inferences, hints, and guesses rather than knowledge; his memory and judgment shade everything. This is also James’s method—suggestion, implication, the vibrations of individual consciousness rippling through all of the novel’s “factual” questions.

The most important limitation is that the reader experience events only through Strether’s point of view—or, rather, through James’s rendering of Strether’s point of view. James, writing in the novel’s preface, notes that this was always the “major propriety” of the novel—“employing but one centre and keeping it all within my hero’s compass.”

Other persons in no small number were to people the scene, and each with his or her axe to grind, his or her situation to treat, his or her coherency not to fail of, his or her relation to my leading motive, in a word, to establish and carry on. But Strether’s sense of things, and Strether’s only, should avail me for showing them; I should know them but through his more or less groping knowledge of them, since his very gropings would be among his more interesting motions. . .

In this adherence to a single subjectivity, James prefigures the modernists, for whom the operation of consciousness and the limitations of viewpoint would be defining characteristics. But James has no interest in stepping out of the way to imitate consciousness, as Joyce or Faulkner did. James is going to tell us the story; he is not going to turn Strether, in his words, into both “hero and historian.” The subject and the setting is Strether’s consciousness—even Paris itself, so seductively rendered, is a Paris of Strether’s own narrow experience. This is part of the genius of James, the quality that inclines me to call him the master of subjective consciousness in narrative even after a century of first-person tales and unreliable narrators and streams of consciousness followed this novel’s publication in 1903. He attempts to observe and describe consciousness in the same way that Rick Bass attempts to observe and describe the Yaak Valley of Montana. James is the historian, and Strether is the hero, and we are pinned in place by all that they won’t tell us—by the law of the incalculable.

If we were to discover what they make back in Wollett, it would do us no favors.

Shawn Vestal’s first book, the short story collection Godforsaken Idaho, won the 2014 PEN Robert W. Bingham Prize and was shortlisted for the Saroyan Prize. Vestal’s fiction has appeared in Tin House, McSweeney’s, and The Southern Review, among other journals, and he also writes a column for The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, where he lives with his wife and son.