By Michael Sragow

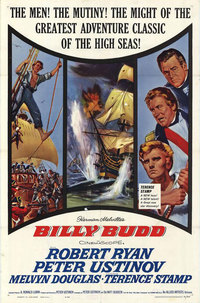

With the aid of a superb cast, this 1962 adaptation wrings a lucid, sinewy narrative from the poetry and moral complexity of Herman Melville’s posthumously published masterpiece.

Few movies enwrap you in their stories with the indelible immediacy of Peter Ustinov’s adaptation of Herman Melville’s unfinished short novel, Billy Budd. As the actors’ credits unfurl onscreen over images of HMS Avenger pursuing the British merchant vessel Rights of Man, each performer states his character and rank on the sound track. We see Robert Ryan’s name and hear him say “John Claggart, Master at Arms, Royal Navy,” then Peter Ustinov’s as he says, “Edwin Fairfax Vere, Post Captain, Royal Navy,” and on to the final acting credit, “Introducing Terence Stamp,” which arrives with Stamp’s brisk, manly declaration that he’s “Billy Budd, merchant seaman.” Usually, spoken credits serve a playful, “meta” function, as they do in M*A*S*H and The Magnificent Ambersons. But this coup de cinéma hurtles us straight into the drama. Before you even see them, the cast delivers a superb team performance, starting with Ryan’s conversational snarl and continuing with the crisp military accents or brine-soaked growls of a remarkable supporting ensemble, including John Neville and David McCallum. When the camera descends to the deck of HMS Avenger, the audience already feels part of this film’s universe.

| READ THE BOOK |

|

| Herman Melville: Pierre, Israel Potter, The Piazza Tales, The Confidence-Man,Billy Budd, Uncollected Prose |

By the time Ryan’s brilliantly rendered Claggart, who stews in his own cynicism and sadism, tells Stamp’s uncannily innocent Budd, “The sea’s deceitful, boy; calm above, and underneath, a world of gliding monsters preying on their fellows,” the hyperbolic language sounds organic. It emerges from the real yet fable-like atmosphere Ustinov has generated onboard.

In his 1977 memoir, Dear Me, Ustinov refers to Claggart as “the embodiment of evil,” Budd as “the embodiment of good,” Vere as “the Pontius Pilate of this Passion,” and the sail-maker known only as the Dansker (Melvyn Douglas) as “the Recording Angel.” But Ustinov’s Billy Budd is a hardy sea story, not a religious parable. It’s unusual among literary adaptations for the way it strengthens rather than diffuses the poetry and moral arguments of the original with heaps of invented action and fresh dialogue (some, like Claggart’s speech above, taken from Louis O. Coxe and Robert Chapman’s 1951 play). It builds to a heartrending climax that also functions as a provocation. Billy Budd is a prime example of the kind of film that gets audiences arguing on their way home from the theater.

Claggart becomes nearly as fascinating and shocking as Iago. What are the roots of his poisonous obsession with Budd, and why does he commit himself to the boy’s downfall by accusing him of being a mutineer? And why is the rational, humane Captain Vere so slow to rein in Claggart? Is it wise for the captain to keep Claggart as master-at-arms until he commits a provable breach of martial law? And is it just for Vere to apply the same law without patience or mercy for Budd? Billy Budd is so engrossing because these questions of ethics and motivation don’t spin out of sea air. They rest on dramatic bedrock: the movie provides a keen understanding of how hierarchy (and tyranny) functioned in the eighteenth century Royal Navy and how the French Revolution threw all of Europe into turmoil.

As the voiceover narrator tells us, it’s 1797, a year of mutiny in the British fleet and “continuing war with republican France.” The Avenger sails toward Spain to reinforce the British squadron off the Iberian coast. Captain Vere hopes to intercept the Rights of Man in order to press members of its crew into service. It takes a warning shot to stop the merchant ship, whose captain is loath to give up any of his men, and the Avenger’s boarding party nets only one seaman who seems fresh, strong, and free of mutinous attitude: the master’s favorite, Billy Budd. When his former skipper calls out, “God go with you Billy Budd, for it’s a fact you go with God,” Budd responds, “Goodbye to you all, and goodbye to you too, old Rights of Man.” The Avenger’s shocked Second Lieutenant Ratcliffe (Neville) snaps, “What do you mean by that, boy?”

Budd is being affectionate, not political, and neither he nor Ustinov, who directed and (with DeWitt Bodeen) cowrote the script, mistakes life on a merchant ship, even one called Rights of Man, for a democratic heaven. In one hilarious shot, its crew lines up for inspection looking like the dregs. In a gigantic, ominous closeup, the ship’s figurehead, a shackled black slave, looms over the audience. (Robert Krasker, Ustinov’s cinematographer, was a legend who ranged from epic comedies like Caesar and Cleopatra to classic dramas like Brief Encounter.) We believe Budd when he calls it “a good ship,” and his skipper tells him “you helped make it good.” Budd soon learns that a man o’ war like the Avenger can be a regimented inferno.

As a merchant seaman, Budd shared in every sort of shipside job, but right after he enters the Avenger’s ranks, Claggart assigns him to the foretop. Before Budd can settle in his hammock, Claggart calls the crew on deck to witness a flogging. The camera takes in Budd’s shock, his wistful backward glance at Rights of Man, the rueful or shamed attitudes of crewmen and officers, and the agony of the victim. Claggart, though, evinces cool delight—until he’s startled to see Billy Budd appraising him.

Flogging is new to Billy, and he can’t make sense of it. The Dansker explains that the victim “may have spat against the wind, or mumbled in his beard; it may have been a prayer; to them it was a protest.” In an age of mutiny, flogging fits any crime or insult to authority. For the first time we witness Billy’s stammer—his inability “to find the words for what I feel”—before he says that spread-eagling a man against a spar and whipping him is “against him being a man.”

In just fifteen minutes, writer-director Ustinov establishes the dense, risky environment of Herman Melville’s posthumous short novel, which was incomplete at his death in 1891 and published in an unreliable edition in 1924. Ustinov said he focused on the dilemma of officers like Vere being “compelled by the letter of the law to carry out sentences which they don’t wish to do.” It’s a tribute to his instincts as a filmmaker that his characters and their worldviews exert an even deeper fascination than this tragic paradox. He plants their elemental conflicts and moral, ethical debates in a dense, vivid tapestry of naval life.

In many ways, Ustinov was in his wheelhouse—he was part of a generation of veterans. During his British Army service in World War II, he had collaborated with thriller-writer Eric Ambler and the great director Carol Reed (best known for Odd Man Out and The Third Man, both shot by Krasker) on the famous propaganda feature The Way Ahead, which dramatized a lieutenant (David Niven) molding conscripts into a fighting unit. Ustinov himself despised being in the army: he called it “a nightmare school for backward adults, in which degrees could be achieved in monstrous disciplines.” In the 1950s, the patriotic battle anthems of World War II had given way to critical portraits of military service, like Fred Zinnemann’s adaptation of James Jones’s From Here to Eternity. (Before producing, directing, co-writing, and starring in Billy Budd, Ustinov had done a delightful turn for Zinnemann as a drifter Down Under in The Sundowners, followed by his Oscar-winning performance as the slave owner of a gladiatorial academy in Kubrick’s Spartacus.) Ustinov’s belief that “National Service is the only dictatorship permitted in a democratic society” underlay his war stories on talk shows and helped him wring a lucid, sinewy narrative from Melville’s Billy Budd. Ustinov’s adaptation was actually one of three British Navy mutiny pictures, set roughly in the same era, to come out in 1962. The others were the remake of Mutiny on the Bounty and Damn the Defiant! Billy Budd does by far the most gripping and profound job of immersing you in a system so dehumanized that it tolerates a devil like Claggart and crushes a saint like Billy Budd.

Coxe and Chapman’s play had already augmented the slender action of Melville’s novella with freshly minted incidents of Claggart sending a sick sailor aloft and Budd having a heart-to-heart (or heart-to-heartless) with the master-at-arms at night. Ustinov and Bodeen’s script retains and reworks those innovations, contributes a few of its own (like Vere’s ordering the cannoneers to unload on a French ship out of range, simply to defuse the tensions on the ship), and adds events from the novella that would have been difficult to stage, such as Budd’s recruitment from the Rights of Man. What sustains the film’s suspense is its piquant clarity about the everyday dangers of an eighteenth century sailor’s life (an exotic extra for today’s audiences, now that Tall Ship adventures are no longer a popular genre). Ustinov and Krasker exploit nautical space to brew up an enveloping aura. They convey the emotional and physical dynamics of every onboard experience, from the sailors sleeping on hammocks in close quarters to the vertiginous loneliness and fear of a foretopman climbing the foremast. Their visual limpidity enables us to “read” the class bias built into the architecture of the ship, from the quarter deck down to the hold, as easily as we do the gaps between upstairs and downstairs on Upstairs, Downstairs or Downton Abbey.

“I leaned heavily on that consistently extraordinary battalion of British character actors which are the real backbone of our theater,” Ustinov wrote. “Behind the leaders stood that cohort of wonderful talent,” including Paul Rogers as Vere’s First Lieutenant Seymour, Niall MacGinnis as the Rights of Man’s skipper, and Lee Montague as Claggart’s colluder, Squeak. Because of the depth of Ustinov’s cast, there’s never a dead spot on the screen. Ustinov’s “leaders” are even more extraordinary. Though Ustinov lauded Ryan’s “massive and wicked presence onscreen,” what’s hypnotic about his Claggart is its depth and lived-in detail. According to Ryan’s biographer J. R. Jones, the actor campaigned for a role in this movie, but it’s hard to imagine him in any other. Claggart is Budd’s perfect opposite. Claggart is tight-lipped about his shady past; Budd is cheerful about being a bastard. Claggart is as handsome as the foretopman is beautiful, as shrewd as Budd is intuitive, as attached to the world’s depravity as Budd is free of it. Ustinov and Krasker exploit how perfectly Ryan looks the part; Claggart seethes with Ryan’s boundless dark vitality. His expressions of fascination for “the handsome sailor” don’t preclude erotic intrigue and self-loathing. What’s paramount to Ryan’s conception is that Claggart considers Budd’s very existence a primal threat to his shark-eat-shark identity and philosophy. You can imagine him saying about Budd what Iago says about Cassio: “He hath a daily beauty in his life / That makes me ugly.” There’s an athletic rhythm and charisma to Ryan’s performance, especially when Vere restricts him to counting out only ten strokes for a flogging and he reflexively keeps lashing his own leg with a baton. Ryan reaches his peak after Claggart finally goads Budd into striking him. His face displays shock transforming to delight—a bone-chilling jolt for the audience—and then resignation when he realizes that the blow is mortal. The glory of Ryan’s acting is that he brings nuance to this villain without softening his primal force. You can understand why, on a masterly episode of The Sopranos, Carmela Soprano contended that the movie is simply about “an innocent sailor being picked on by an evil boss.”

In his memoir, Ustinov refers to Stamp then as “an unknown, a hesitant, uncertain young actor.” As Stamp confides to Steven Soderbergh on the audio track of the DVD, the director gave his discovery the confidence and space to find his emotions in the moment and dare to do nothing or be still (which became Stamp’s acting trademark). Stamp was nominated for an Oscar for his first film, and considering how difficult it is to portray goodness, it’s astonishing that it hasn’t become an even more legendary performance. Stamp has the intelligence never to try to embody “virtue,” but to play qualities like cheerfulness and bonhomie instead; he imbues Budd with a surprisingly elastic sort of simplicity. You believe he means everything he says, whether he’s trying in vain to befriend Claggart or yelling out, before he hangs for Claggart’s death, “God bless Captain Vere!”

Melville biographer, scholar, and editor Hershel Parker says he had been “typing some of the notes for the Harrison Hayford–Merton M. Sealts Jr. edition of Billy Budd, Sailor”—the definitive version, included in the Library of America—“in Hayford’s cramped attic” in 1962, before seeing the movie later that year. As Parker put it in a recent email to me, a signal contribution of the Hayford–Sealts Jr. edition is its proof “that Melville died with his characterization of Vere going in two divergent directions.” Parker notes in his magisterial textual analysis, Reading Billy Budd (1990), that Vere changes from Budd’s loving surrogate father to “strict military disciplinarian” with appalling abruptness. The ship’s surgeon even suggests that Vere’s call for the swift trial and punishment of Budd indicates an onset of insanity. The first time he saw the film, Parker thought that the playwrights and filmmaker tried in vain to reconcile the divergent aspects of Vere simply by creating in First Lieutenant Seymour a character who would allow the Captain to debate with the paternal, empathetic side of himself.

Pauline Kael was the movie’s most prominent contemporary champion. She did criticize Ustinov’s Vere, but took a different tack, contending that because of the way Ustinov interprets him, “as a human figure tragically torn by the rules and demands of authority,” the film becomes nothing more “than a tragedy of justice.” Kael summarizes her vision of the Captain with characteristic éclat: “Sweet Starry Vere is the evil we can’t detect: the man whose motives and conflicts we can’t fathom. Claggart we can spot, but he is merely the underling doing the Captain’s work: it is the Captain, Billy’s friend, who continues the logic by which saints must be destroyed.”

Actually, as Vere, Ustinov is superb at expressing quicksilver sympathies and an intriguing intellect. Ustinov doesn’t ignore Vere’s temporary lunacy: he puts it somewhere else. In the film, unlike the book, Budd’s hanging instantly and totally undoes the Captain. He staggers across the poop deck in a daze. He abdicates his authority, telling his first lieutenant Seymour, “You may do as you wish, Mr. Seymour, it is of no further concern to me.” Even under fire, he removes himself from command—an act that seems a kind of suicide. A French blast leaves him with a torn sail as his shroud.

Watching the film again in 2015, Parker told me he felt confirmed in his judgment that Seymour was manufactured as a foil to Vere. But this time he “did not worry about whether the movie was faithful to Melville or not. It’s not, but it’s awfully good, except for the slap bang ouch thud last minute or so. . . . Terence Stamp was wonderful, especially his diffident smile that started very slowly so you were not really sure whether he was going to let it broaden out.”

Budd says that flogging a sailor is “against him being a man.” Vere says, at the end, “I’m only a man, not fit to do the work of god or the devil.” Ustinov proves himself fit to do both. His Billy Budd is more than robust—it’s Shakespearean: it explores what a piece of work is man.

Turner Classic Movies airs Billy Budd on May 13. Click on the date for further information.

Original theatrical trailer for Billy Budd (2:59)

Billy Budd (1962). Directed by Peter Ustinov. Written by Ustinov and DeWitt Bodeen from Herman Melville’s novella and a play by Louis O. Coxe and Robert Chapman. With Terence Stamp, Peter Ustinov, Robert Ryan, and Melvyn Douglas.

Buy the DVD • Stream on Google Play

Michael Sragow is the curator of Library of America’s Moviegoer feature. He is the West Coast Editor and a film critic for Film Comment and author of Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master.