By Farran Smith Nehme

The 1994 version of Louisa May Alcott’s beloved novel has much to recommend it, including Winona Ryder as a “less fierce, more vulnerable” Jo March—but Katharine Hepburn, in George Cukor’s 1933 adaptation, fit the part “as no other actress ever has or perhaps ever will.”

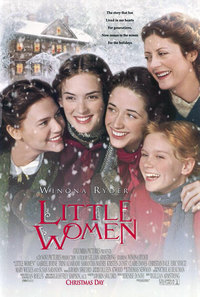

Sometime between her ninth and twelfth birthdays, a certain type of bookish girl reads Little Women. Certainly boys read it too, and others read it as adults. But for many young women who encounter it just as adolescence hits, Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 classic turns the March sisters—dutiful Meg, rebellious Jo, doomed Beth, and vain Amy—into permanent memories. “Some books are so familiar reading them is like being home again,” says Winona Ryder, narrating the 1994 film in her role as Jo. That non-Alcott line is meant to evoke how millions of people feel about Little Women.

| READ THE BOOK |

|

| Louisa May Alcott: Little Women, Little Men, Jo’s Boys |

First filmed as a silent in 1918, the novel (originally published in two parts) spins out interlocking tales of how the March sisters and their saintly mother, Marmee, support and squabble with one another as they cope with meager income and a father away at the Civil War. Jo writes Walter Scott–ish tales and begins a close friendship with Laurie, the rich boy next door; Meg marries a nice young man and settles down; delicate Beth soothes her sisters’ troubles even as her own health worsens; Amy paints and frets over her lack of pretty things.

These episodes are a gift to a filmmaker. They can be shuffled around in a script like a deck of cards, as long as the key events are kept intact, and as long as one truth is observed: Brash, impulsive, and bursting with frustrated intelligence, Josephine March is the heroine. You may prefer another character. Cathy Horyn once wrote a ringing defense of Amy for The New York Times, some gentle souls aspire to be Beth, and there may be a few (rarely spotted in the wild) who prefer Meg. But Jo is the fiery soul of this story. If you don’t love Jo, at least a little, you cannot love Little Women.

Thus the film versions of the book succeed or fail on the basis on the actress performing Jo. When director George Cukor took on the project for RKO in 1933, he had to cope with a pregnant Amy (Joan Bennett, who wore a lot of pinafores), a somewhat too old and staid Spring Byington as Marmee, and a toothy, yet toothless, Douglass Montgomery as Laurie—yet it didn’t matter. Cukor famously didn’t read the book before filming, and years later his film’s star laughed that she didn’t think he ever did get around to it. But that star, Katharine Hepburn, was Cukor’s greatest advantage.

Like Alcott, Hepburn came from an old and progressive New England family, and she fit the part of Jo as no other actress ever has or perhaps ever will. “Christopher Columbus!” bellows Hepburn’s Jo, her hair flying around her as though she’s the lookout for the Santa Maria. Tall, lanky, with a chiseled face that could look plain one moment and stunningly gorgeous the next, Hepburn has a rangy physicality that seems to push against the very walls of the March house. Her Jo is not self-dramatizing (that’s Amy’s department) but unfiltered, all of her emotions right on the surface.

Jo’s frank admiration of Laurie’s wealth, and the March sisters’ scrimping and saving, were all too familiar to a Depression-racked audience. RKO was not a wealthy studio, but the black-and-white cinematography (by Henry W. Gerrard) and somewhat cramped sets gave everything the feel of an old lithograph; Max Steiner contributed a delicate, unusually stripped-down score.

Given the leisurely pace of Alcott’s novel, this is a fleet movie. The script (credited to Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman) accomplishes that in part by excising large chunks of the original narrative, including the domestic travails of Meg (Frances Dee). One minute, she is marrying John Brooke (and giving her first post-marital kiss to Marmee, in a gesture that plays as deeply weird now), and the next, she has twins. The screenwriters also condense the touching relationship between Beth (Jean Parker) and old Mr. Laurence (Henry Stephenson), Laurie’s father, in a way that reflects the movie’s era. Beth sitting on the old man’s lap is a tender moment that might unnerve modern audiences.

So it is Hepburn as Jo that remains forever fresh and undated: Jo mourning by an open window at night, after rejecting Laurie’s marriage proposal; Jo breaking down into racking sobs after selling her glorious hair for money; Jo, glowingly beautiful on the steps of an opera house, as she talks to Professor Bhaer (a well-cast Paul Lukas) just before she gets word that Beth is deathly ill.

There is a 1949 version, directed by Mervyn Le Roy at MGM, but it feels hollow. There was no need to emphasize Alcott’s lessons on how to patch a gown and make do with only one set of good gloves to a post-Depression, postwar audience; these girls go shopping, too. At the time, MGM was less interested than ever in pushing the boundaries as far as women’s roles were concerned, and thus June Allyson, the simpering, chirpy wife in so many bland films, is appallingly miscast as Jo. The other girls (Janet Leigh as Meg, Margaret O’Brien as Beth and Elizabeth Taylor, possibly the world’s most famous brunette, as blonde Amy) barely leave an impression. Meanwhile, Mary Astor, as Marmee, has a steely look about her eyes that suggests she might morph into The Maltese Falcon’s Brigid O’Shaughnessy and send these ninnies up the river.

Aside from an unloved 1978 TV version, it took almost fifty years for a successfully refashioned Little Women to arrive, and it came through the efforts of Winona Ryder, who wanted to play Jo. What was more, for the first time a woman, Gillian Armstrong (who’d made her name with My Brilliant Career, another tale of a future writer), directed.

From the opening sounds of Thomas Newman’s music, this Little Women is a lusher affair. The movie, filmed mostly on Vancouver Island, takes much of its appeal from the changing seasons and sense of hurtling time captured by cameraman Geoffrey Simpson. The March girls know that their days as a contented unit are slipping away, and yet they are also rushing to meet adulthood.

Ryder presents one difficulty: When she cuts off her hair and the March sisters call it Jo’s “one beauty,” it’s hard not to reflect that this Jo is by far the prettiest actress in the movie. Neither does Ryder have Hepburn’s overpowering screen charisma. But screenwriter Robin Swicord restores certain scenes that didn’t make it into Cukor’s version (Amy burning Jo’s manuscript, for example) and also weaves in many factors from Alcott’s own life. Ryder may not fire up the screen as Hepburn did, but she brings real tenderness to her version of Jo, most obvious in her scenes with Danes as Beth. Ryder plays Jo as a woman whose ambition is tied tightly to love of family; she is less fierce, more vulnerable.

This more stable and sensible Jo narrates the movie as though from the novel she eventually writes, and she gives her sisters more time in the spotlight. Meg’s (Trini Alvarado) brief attempt at becoming a socialite is restored; Amy, played by Kirsten Dunst as a youngster and a less engaging Samantha Mathis later on, is far more present; and Claire Danes as Beth suggests that there are mental reasons (agoraphobia? depression?) behind her being the “angel in the house.” Susan Sarandon is a feisty proto-feminist Marmee, treating Beth’s illness with homeopathy and denouncing corsets to a startled neighbor.

There’s an element of wish fulfillment in this outing. For many women, Jo’s refusal to marry Laurie is one of the earliest and keenest literary disappointments of them all. Armstrong and Swicord work hard to cushion the blow. True, Christian Bale, open-faced, kind and uncomplicated, is the most appealing of the movie Lauries, and Jo’s rejection still stings. But Laurie’s relationship with Amy, the March sister he winds up with, is foreshadowed carefully. And this movie’s Professor Bhaer is no sexless consolation prize; instead, we are given handsome and dashing Gabriel Byrne.

The 1994 version was a resounding hit, and when yet another Little Women was recently mooted, some websites discussed Ryder, Bale and Danes as though there had never been a previous film. Fans of Alcott’s novel can only be happy that the March girls still provoke discussion, but let’s hope that Cukor and Hepburn are never forgotten. The closing moments of that black-and-white film, when Jo pulls Professor Bhaer out of the rain and into her home, sum up the story’s appeal for all time. The March family is loving enough to fold everyone into it.

Trailer for the 1933 version of Little Women (3:02)

Little Women (1933). Directed by George Cukor. Written by Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman, from Louisa May Alcott’s novel. With Katharine Hepburn, Joan Bennett, Jean Parker, Frances Dee, and Spring Byington.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Google Play • Watch on iTunes

Little Women (1949). Directed by Mervyn LeRoy. Written by Andrew Soit from the 1934 screenplay and Alcott’s novel. With June Allyson, Janet Leigh, Margaret O’Brien, Elizabeth Taylor, and Mary Astor.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes

Little Women (1994). Directed by Gillian Armstrong. Written by Robin Swicord from Alcott’s novel. With Winona Ryder, Claire Danes, Kirsten Dunst, Samantha Mathis, Trini Alvarado, and Susan Sarandon.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film at her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and in a weekly column for filmcomment.com. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Post, The Wall Street Journal, Barrons, and Sight and Sound. Her novel Missing Reels is out in paperback from the Overlook Press.