Our series of guest blog posts by writers of fiction, history, essays, and poetry continues today with a contribution from J. Aaron Sanders, whose debut novel, Speakers of the Dead, is released this week.

Both a mystery and a work of alternate history, Speakers of the Dead stars none other than Edgar Allan Poe and Walt Whitman in the unlikely role of crime-solving duo. Below, Sanders recounts how a gruesome real-life nineteenth-century homicide provided the inspiration for his novel.

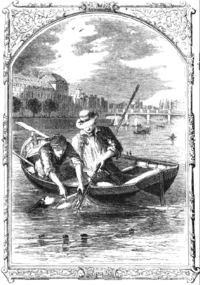

When the battered body of cigar girl Mary Roger turned up in the Hudson River on July 28, 1841, the ghastly nature of the crime sent New York City into a panic. Her beautiful face had been bludgeoned so that she was barely recognizable, and her corpse was swollen with water. A large crowd had gathered by the time the body was brought ashore, which in practical terms meant that many ordinary citizens saw what had happened to Mary Rogers with their own eyes. Add to this the newspapers’ wild speculative reporting, and the fact that the police failed to find the culprit, and city’s alarm escalated further.

In his book The Beautiful Cigar Girl (2006), Daniel Stashower writes that the Mary Rogers murder “became a catalyst for sweeping change” in 1840s New York City. Law enforcement was exposed as inadequate. The sensational details gave rise to sensationalism. And murder became “a bankable commodity.” Edgar Allan Poe decided to take on the murder in a desperate attempt to restart his career with his fictional attempt to solve the murder, a three-part story called “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” (collected in the Library of America volume Edgar Allan Poe: Poetry and Tales). Poe, who was living in Philadelphia at the time, had resigned from his position at Graham’s magazine after he was relieved of his duties as associate editor, a decision that left him and tuberculosis-stricken wife, Virginia, in “abject poverty.” Poe struggled to find a publisher for “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” and when an attempt to launch a bidding war between Joseph Snodgrass of the Sunday Visiter and George Roberts of the Boston Notion failed, Poe had to settle for William Snowden’s Ladies’ Companion, a magazine he detested—marking an inauspicious beginning for the down-and-out author.

In “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” a sequel to “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Poe used his detective C. Auguste Dupin to do something that had never been done before: solve a real crime using fiction. The story was published in three parts in Snowden’s Ladies Companion: the first installment in November 1842, and the second in December. The third installment was delayed after a newspaper article suggested that Mary Rogers died of a botched abortion attempt and not murder. This new theory completely debunked Poe’s own, and though he changed some of the story to reflect the new information, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” didn’t have the intended effect.

It is precisely this fact that makes “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” the perfect way to frame my novel Speakers of the Dead. In it, a young Walt Whitman attempts to solve the murder of a friend, Abraham Stowe, a doctor suspected of botching the abortion that killed Mary Rogers (Stowe’s character is pure fiction). To find out who killed Abraham Stowe, Walt must take on the unsolved Mary Rogers murder, and so he seeks out the help of the one person who knows more about it than he does: Edgar Allan Poe.

Each author’s motive is clear. Whitman wants to solve the murder to exonerate his friend, and Poe wants to solve the murder to finish what he started in “The Mystery of Mary Rogêt.” The two men become unlikely allies, and their time together culminates in a scene where they join forces in a graveyard stakeout. Avoiding spoilers, I’ll just say that Poe bails Whitman out of some trouble by creating a diversion:

Mr. Poe’s voice catches Walt and the sheriff by surprise. It sings from the darkness, from an invisible space as if from the graves themselves: “We have put her living in the tomb,” he calls out. “I now tell you I heard her first feeble movements in the hollow coffin. I hear them even now.”The voice continues: “Have I not heard her footsteps on the stair? Do I not distinguish that heavy and horrible beating of her heart?”

Mr. Poe springs furiously from the wagon and charges the sheriff, who fires a warning shot in the air.

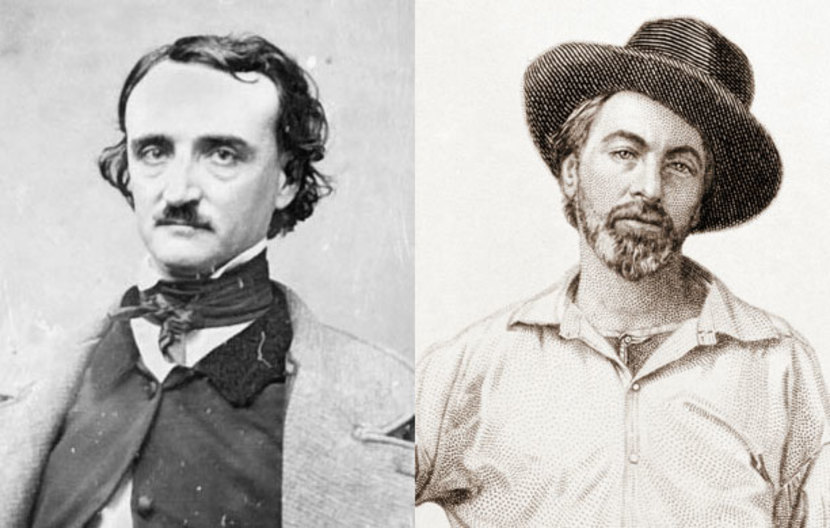

Of course I’m taking great liberties here. Speakers of the Dead is a mystery novel, and I have played fast and loose with history in service to the genre. Walt Whitman and Edgar Allan Poe are beloved figures, and my novel brings them to life in unexpected roles and within a suspenseful narrative. Although they didn’t solve mysteries together in real life, Whitman documented their one meeting in Specimen Days:

I also remember seeing Edgar A. Poe, and having a short interview with him, (it must have been in 1845 or ’6,) in his office, second story of a corner building, (Duane or Pearl street.). . . . Poe was very cordial, in a quiet way, appear’d well in person, dress, &c. I have a distinct and pleasing remembrance of his looks, voice, manner and matter; very kindly and human, but subdued, perhaps a little jaded.

There are no body snatchers, graveyard stakeouts, or unsolved murders in this unremarkable meeting. Instead we have two of our greatest American writers in the same room at the same time, and that alone is remarkable.

J. Aaron Sanders teaches literature and creative writing at Columbus State University, where he is an associate professor of English. He holds a PhD in American Literature from the University of Connecticut and an MFA in Fiction from the University of Utah. His fiction has appeared in The Carolina Quarterly, Gulf Coast, Quarterly West, and Beloit Fiction Journal, among other publications.